Auction: 25111 - Orders, Decorations and Medals - e-Auction

Lot: 544

(x) Seven: Staff Sergeant G. S. Gilmore, a member of Detachment A-502 United States Army Special Forces, late Royal Army Service Corps

General Service 1918-62, 1 clasp, Malaya (T/22523477 Cpl. G. S. Gilmore. R.A.S.C.); United States of America, Army Commendation Medal with three oak leaf clusters; Good Conduct Medal; National Defense Medal; Vietnam Service Medal; Antarctic Service Medal; South Vietnam Medal, clasp 1960, mounted as worn, good very fine (7)

Army Commendation Medal awarded for Meritorious Service in the Republic of Vietnam during the Period 15 December 1967 - 15 December 1968.

'Staff Sergeant G. S. Gilmore, RA19760251 United States Army who distinguished himself by exceptionally meritorious service in support of allied counterinsurgency operations in the Republic of Vietnam. During the period 15 December 1967 to 15 December 1968 he astutely surmounted extremely adverse conditions to obtain consistently superior results. Through diligence and determination, he invariably accomplished every task with dispatch and efficiency. His unrelenting loyalty, initiative and perserverance brought him wide acclaim and inspired others to strive for maximum achievement. Selflessly working long and arduous hours, he has contributed significantly to the success of the allied effort. His commendable performance was in keeping with the finest traditions of the military service and reflects distinct credit upon himself and the United States Army.'

Army Commendation Medal (First Oak leaf Cluster) for Meritorious Service United States Army, Ryukyu Islands and Fort Buckner 10 January 1969 - 16 January 1970.

'By direction of the Secretary of the Army, the Army Commendation Medal is awarded for exceptionally meritorious service to the United States Army. The leadership, professional competence, and devotion to duty exhibited in the performance of all assigned and assumed duties contributed immeasurably to the successful accomplishment of the unit's mision. Through his initiative and perserverance he has shown himself to be a key individual to the organization, which has been proved time and time again by his ability to perform extremely difficult and important tasks in an original, unprecedented and clearly exceptional manner. His outstanding performance and meritorious service throughout this entire period are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect the utmost credit upon himself, this command, and the United States Army.'

Army Commendation Medal (Second Oak Leaf Cluster) United States Army Headquarters, 2d Logistical Command APO San Francisco 96248 for Meritorious Service January 1970 - September 1970.

'By Direction of the Secretary of the Army, The Army Commendation Medal, Second Oak Leaf Cluster, is awarded to Staff Sergeant Gordon S. Gilmore, 552-68-7676, for exceptionally meritorious service as Boatswain, Third Mate, Chief Mate, Transportation Company, Transportation Battalion Provisional, 2d Logistical Command, United States Army, From 26 January 1970 to 4 September 1970. The leadership, professional competence, and devotion to duty exhibited in the performance of all assigned and assumed duties contributed immeasurably to the successful accomplishment of the unit's mission. Through his initiative and perserverance, he demonstrated outstanding performance of extremely difficult and important tasks. His exceptional achievement and meritorious service throughout this period are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect great credit upon himself, the 2d Logistical Command, and the United States Army.'

Gordon Stewart Gilmore was born at Clerkenwell, London on 28 June 1932 and enlisted into the Royal Army Service Corps on 6 June 1950 and completed 12 years service seeing service as part of FARELF between 10 January 1951 and 23 November 1953, again between 3 December 1956 and 26 February 1958, and with further service in Hong Kong from 26 February 1958 until 14 December 1959 and finally again between 27 June 1961 and 5 June 1962. On his discharge he settled in New Zealand and resided at the Mission to Seaman in Auckland. His testimonials note him as being a Coxswain of a Motor Fishing Vessel as well as commanding other Vessels during his time of service. Gilmore enlisted into the United States Army in the early 1960's and served in Vietnam with the United States 5th Special Force Group (Airborne), Detachment A-502 in 1967.

A-502 in Vietnam

In 1965, 5th Group Headquarters determined the need for two -Teams in the Nha Trang area, but with each having different responsibilities. This determination resulted in the authorisation and establishment of Detachment A-503, which would assume the responsibilities of A-502. Because of their familiarity with the mission, key members of A-502 were assigned to the new team. the XO (Executive Officer) of A-502 became the CO (Commanding Officer) and Team Leader of the new A-503 team.

Released from its original assignment, A-502 was given an even greater mission. It would become responsible for the security of the entire Nha Trang area. Overnight, the team's AO (Area of Operation) and responsibilities became significantly larger. With the acceptance of its new mission, A-502 would also begin to create its history as the largest Special Forces A-Team ever to exist.

Relocating in Khanh Hoa Province to the village of Dien Khanh, A-502 establisged its new base in what appeardd to be part of a Hollywood set. The team's new home was the southern portion of an old Vietnamese fort. French forces occupied South Vietnam prior to the involvement of the United States of America. The fort was originally constructed by the Vietnamese under the Nguyen Ahn Dynasty in 1793. It was home to units of the French Foreign Legion's 2nd Colonial Infantry beginning in the early 1940's and could have easily served as a set for an old Humphrey Bogart movie.

However, in 1945, the Viet Minh attacked and overran the fort, claiming the strategic location for themselves. After being held by these enemy forces for several months, it was retaken by the French in a coordinated counter-attack. Reinforcing units of the 6th Colonial Infantry were landed in Nha Trang. Linking up with General Leclerc's 2nd Armoured Division Task Force, the two units mounted their counter-attack and reclaimed the fort they had dubbed the "Dien Khanh Citadel".

The words of his officer Bob Sweeney wrote of the patrol's experiences and in particular their drawing on the tactics of the SAS and their service in Malaya. It would seem likely that he would have drawn on the seperiences of Gordon Gilmore in doing so:

'To accomplish the mission of providing for the defense of Dien Khanh district and for the western defense of the city of Nha Trang, Detachment A-502 (Det A-502) conducted various combat and intelligence gathering operations. The reconnaissance patrolling tactics and techniques employed by U.S. Special Forces in Vietnam came from the British Special Air Service (SAS) experiences gained during counter-insurgency operations that were successfully employed by the SAS when they fought against the communist insurgents in Malaysia 1956-1960. Patrolling, raids, and ambushes, as a guerilla, became a key component of the Unconventional Warfare training taught to U.S. Special Forces at FT Bragg, N.C.. Those jungle fighting and patrolling skills were reinforced by the combat lessons learned from U.S. Special Forces soldiers fighting the Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Army (VC/NVA) in the jungles, mountains, and swamps of Vietnam.'

With the major buidup of conventional U.S. forces in Vietnam in 1966, General Westmoreland tasked the 5th Special Forces Group to establish an in country "RECONDO " school to train U.S. Army soldiers how to conduct Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRRPs) deep into enemy occupied territory. The fearless all volunteer U.S, students underwent a physically and mentally gruelling 18 - hour pe day, 3 weeks of combat reconniassance patrol training. The RECONDO training prgram culminated with a 4 to 5 day live fire, in-the-field, combat patrol against VC/NVA enemy force on the Grand Summit mountain and in the always dangerous jungle mountains in the operational ara of Det A-502.

Of the five 13 man CIDG Companies at Camp Trung Dung, two were ethnic Vietnmese. The other three companies were ethnicaly from several Montagnard tribe They joined the CIDG program to serve as close to their homes as possible. When in camp three hot meals and clean barracks were provided. To be drafted into the Vietnamese Army and meant fighting, dying, and to be buried away from their ancestors. The professional reputation and the respect of the CIDG from U.S. Special Forces also significantly helped the recruiting and retention of the CIDG. In a firefight the CIDG could count on us to be fighting right along side them. And if they were wounded we would get them to an excellent hospital run by the U.S. Special Forces medics, not to the notoriously bad Vietnamese Army hospital. Each month i would prepare the payroll and the U.S. Special Froces Sergants assigned to each of the CIDG companies, as advisors would pay them. If a CIDG soldier were killed, we would also make sure that his survivors got six-month pay cash payment.

The Long Range Combat patrols from Det A-502 were of 5 to 10 days long and were conducted into the enemy controlled jungle-mountains of the Dien Khanh District's Song Cai River Valley. Covered in triple canopy jungle growth, these extremely rugged mountains rapidly rose from sea level to 3000 to 4000 feet and surrounded the valley on three sides... in a U shape. The Det A-502 combat patrols consisted of the 40 man Recon Platoon, or a 132 man CIDG Company, or a 132 man CIDG Company with the Recon Platoon scouting ahead at the front. Usually at least two U.S. Special Forces advisors, two Vietnamese (VN Special Forces, and an interpreter would accompany the CIDG forces. The CIDG, although small in height, were as strong as mountain goats and were very familiar wih operating in the jungles. The indigenous Montagnards were especially at home in their native jungle environment. In addition, the CIDG welcomd the extra combat pay they received for each day on patrol. Although essential, these patrols were not without cost in that many of the CIDG returned with Malaria and would be a long time recovering.

Combat Patrols usually were organised and planned at Det A-502 Camp Trung Dung HQ. Patrols would depart the camp in the late afternoon and spend the night in a local village at the edge of the jungle, then slip into the jungle just before dawn. In so doing, most of the perfume aromas of soap, shaving cream, and other smells that can carry in the jungle air and give away your presence would be eliminated. For the duration of the patrol, no one would bath or shave. Nor did we talk out loud ... only in whispers or hand signals, and only when essential. All human sounds and smells are unusual in the jungle and can carry big distances revealing your positions. Accordingly, we wore no flak jackets, steel helmets, or exposed metal that would sound off when a branch snaps back and hits you. Even our dog tags were taped together. The pace of march was deliberately slow to avoid scaring animals away. The jungle is in fact very noisy and is filled with sounds of birds, monkeys and other animals calling out as well as the natural sounds of tree limbs breaking off or water trickling. The scariest sound in the jungle is silence. When you hear it get quiet....danger awaits.

A day on patrol in the jungle began quietly at first light, although that might not actually be until 7a.m. or later in that triple canopy jungle, keeps the jungle floor rather dark. Direct sunlight rarely penetrates through the three layers of thick jungle growth. After cold breakfast (no fires), we strapped on our gear and in a long single file resumed the patrol. Normally, we followed the trails. For a thousand years people and animals have woven numerous narrow trails in, up, and around the jungle mountains. Hacking through the jungle was too loud, too slow, and too difficult. The pint of the patrol focused it's attention for signs of recent trail use; a scuf mark, bent twigs, a foot print, or other tell tale signs. By observing the CIDG you could note that when they were just waking along holding their weapons loosely, we were relatively safe. But when they slowed down, and were walking bent over tightly holding their weapons at the ready, we were in danger. When in danger, the lead element, in many cases would find a way to avoid enemy contact. Most lng range patrols rarely made contact with the enemy. Because we were long outside of the range of any Artilry FireSupport, and the difficulty of getting any Air Fighter Support (priority always went to U.S. forces) or of getting a MEDAVAC helicopter for the wounded, any contact with the enemy would have put us at a significant disadvantage. The enemy could, and probably also avoided contact with us simply by getting off the trails when he heard us coming, and then spending the rst of the day hiding in the dense growth, waiting until our patrol passed by and was long gone.

By midday our uniforms would be soaked in sweat. As we stopped for a meal, the entire war would stop as the troops took off their gear and started preparing their food on small fires. "Poc time" as it was called was a two hour siesta to compensate for the midday oppressive heat. Apparently both friendly and enemy soldiers did nothing during "Poc time". Noontime stops were made at defensible hilltops so the upward wind currents from the valley below would dissipate the smoke from the cooking fires. After eating, hammocks were strung, shirts and boots removed, and the Vietnamese took a long nap. The Americans usually sat back to back nervously waiting until the Vietnamese awoke and started to patrol again.

Night comes early in the jungle and it is important to find a secure hill top for the Night Defensive Position (NDP). We were careful not to leave a trail or to make a lot of noise as we moved into the NDP. After setting up perimeter security, each man put his equipment where he could easily find it in the dark if we were attacked. But because it was difficult to move at night in the jungle without making a lot of noise, we were generally safe from an enemy attack. We slept in hammocks in a poncho liner blanket fighting off the cold in our damp clothing. Come morning, we once again would begin our long patrol seeking the elusive VC/NVA enemy.

A traditional U.S. Special Forces A Team in Vietnam had approximately three companies of CIDG one hundred men in each. In 1967, Det A-502 had five CIDG Companies with 132 men in each, and one Recon Platoon, performing various combat duties in rotation. One company was in Camp Trung Dung for camp defence; one company was at outpost locations, one company was on ambush, and the other company was a Reaction Force to support the others.

Ambushes conducted in early 1967 usually made at the one hundred men CIDG Company size and were not effective. Intelligence indicated VC/NVA forces were routinely slipping in and out of local villages to gain food supplies. Accordingly, Det A-502 began to set up more and more ambushes. At first the CIDG resisted. They were more at home in the jungle-mountains and believed that large 100 men, company sized ambushes provided safety. With training focusing on noise/light discipline and night firing techniques we were able to put more and more ambushes in the field. Ambush sizes went from a single 100 man ambush, to two 40 man ambushes, and finally five 20 man ambushes. After several months Det-A502 could conduct as many as 15 ambushes in the local area on any given night. Results increased significantly with an average one ambush per night making contact killing the enemy. That's 90 enemy killed in ambush per month with few friendly losses. It was however on the night of November 1, 1967 that while setting up one of these local ambushes the SFC Frank Noe, Det A-502 Medic was killed in action. SFC Noe was a proven and respected combat leader and his loss was mourned by all that knew him.

Ambushes would depart Camp Trung Dung for a local village and initially set up in the open rice paddies facing the mountains...the enemy's most likely point of entry. Because everyone in the village, and anyone hiding in the edge of the jungle saw the arrival of the CIDG forces, the ambush secretly relocated itself to new position an hour or so after dark. In so doing, no one knew the real location of the ambush. If no contact was made with the enemy coming out of the jungle sneaking into the village, it was assumed thatthe enemy had got into the village. sometime after midnight, therefore, the ambush would relocate to another new location and face the village in order to ambush the enemy as they left the vllage returning to the jungle.

A successful ambush is being in the right place at the right time and catching the enemy before he catches you. Lying perfectly still, I waited until the enemy was almost on top of us, then I would toss a grenade totrigger the ambush. Then firing a full magazine of red tracer ammunition I would mark the enemy's position so that the CIDG could know where to shoot. At night it is best to aim low in the hope that a ricochet bullet would hit the target. This deadly volume of fire by the always aggressive CIDG eliminated any enemy resistance in the ambush kill zone. As CIDG poured out lead at a full automatic rate of fire, myself or the U.S. Special Forces advisor with me would "pop" a hand held flare then I would radio Camp Trung dung call sign "Bubkhouse" and request illumination fire from the camps 4.2 " Mortars. A good mortar crew could keep 3 rounds in the air at one time with one flare almost burnt out, one flare burning suspended in the sky by a tiny parachute, and a new round just exploding open. Under the always-eerie flickering flare light, more and more deadly rifle fire would be placed on the enemy in the ambush in the ambush kill zone. A few of the enemy might return fire, but a deadly ambush has all the advantages. When the shooting ended, a search of the enemy bodies would be made and captured weapons would be collected. Captured AK47 rifles indicated NVA, whereas, bolt action rifles were carried by the local VC. Officers used pistols and clean weapons reflected disciplined soldiers. New uniforms versus worn tattered uniforms or civilian clothes indicated the recent arrival of NVA troops from North Vietnam versus a VC farmer by day and guerilla at night. The NVA soldiers had photos of loved ones in their pockets... VC lived in local villages and had their photos at their home.

Those observations and other intelligence questions needed to be answered. Was the enemy entering the village with empty sacks, or were they caught leaving the village loaded down with rice and other supplies. If yes then who supplied them. Does the local village chief sleep in his own village, or does he sleep somewhere else for his family's safety?

The enemy bodies were taken to the nearest village and laid out awaiting identification the next day. If a relative claimed a body, that information could give insight into the VC infrasctructure. An analysis of the answer to these and other questions provides critical information for the development of an accurate military intelligence estimate of the enemy situation.

The CIDG received combat pay for ambushes and prize money was paid for captured weapons. They also received 24 cents per man per month for moral purposes. But at Det A-502 we paid the total amount of the camps moral money to the one CIDG unit with the most monthly enemy kills.

As with long range combat patrol in the jungle-mountains, no one ambush told the whole story of what was going on. But by plotting each ambush that made contact with the enemy on a map, the picture of the enemy activity in local villages became clearer.

As with long range combat patrol in the jungle-mountains, no one ambush told the whole story of what was going on. But by plotting each ambush that made contact with the enemy on a map, the picture of the enemy activity in local villages became clearer.

The Det A-502 limited long range combat patrols in the jungle-mountain did little to dislodge the enemy living there. The results of the numerous local ambushes, however, successfully contributed to our gaining and maintaining security for and control of the local villages throughout the District of dien Khanh, and the approaches to the city of Nha Trang. To win the war, the NVA would have to come down out of the jungle-mountain en masse and fight conventionally. And those battles would have to be to capture the villages and cities of the Vietnamese people.

In the last four months of 1967, the growing frequency of contact with both the VC and NVA units told us that a major buildup and infiltration was going on in preparation for waht was to become a major nationwide battle... the TET offensive of January 1968."

Gilmore was honorably discharged from the United States Army on 23 January 1969 with the rank of Staff Sergeant but re-enlisted with the number 552-68-7676. He purportedly served in Saigon with the U.S.C.I.D. (Criminal Investigation department) tracking down deserters and U.S. service personel involved in criminal activity. Gilmore returned to New Zealand and was employed on the Auckland Wharves. He was run over and killed by a straddle crane in the mid 1980s.

Sold together with the original archive comprising:

(i)

Certificate and Citation for the Army Commendation Medal, in 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) 1st Special Forces folder.

(ii)

Certificate and Citation for the First Oak Leaf Cluster to the Army Commendation Medal.

(iii)

Certificate and Citation for the Second Oak Leaf Cluster to the Army Commendation Medal.

(iv)

Honorable Discharge certificate dated 23 January 1969.

(v)

Special Forces beret (appears unworn).

(vi)

Copied service papers from his service with the British Army.

(vii)

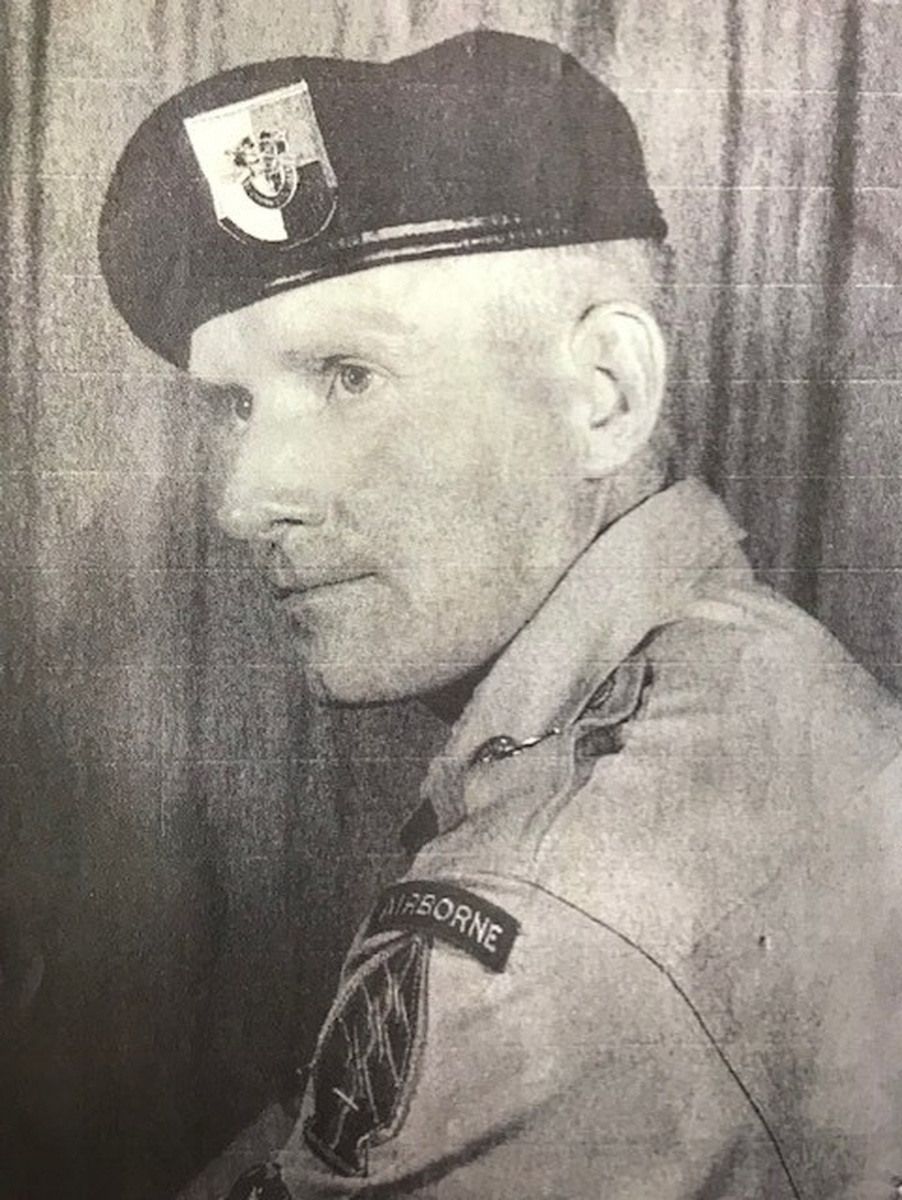

Images of him in U.S.A. Special Forces uniform attached to Detachment A-502.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£1,000

Starting price

£320