Auction: 4020 - Orders, Decorations, Campaign Medals & Militaria

Lot: 471

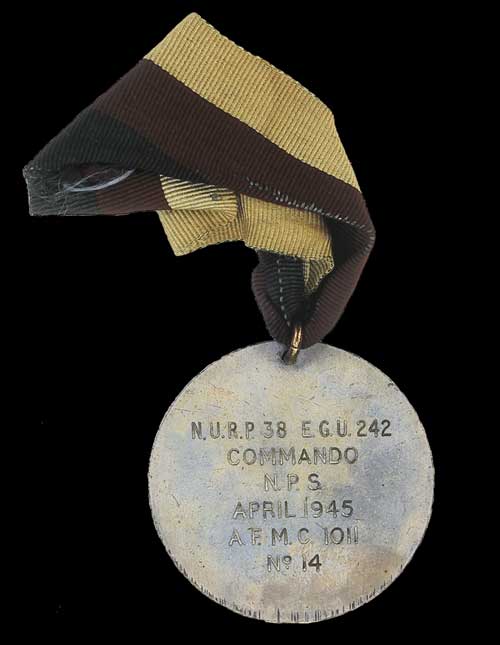

The P.D.S.A. Dickin Medal to Commando Dickin Medal (N.U.R.P. E.G.U. Commando N.P.S. April 1945 A.F.M.C. 1011 No.14), very fine, with two original aluminium message cannisters, and a framed photograph Estimate £ 5,000-7,000 Dickin Medal, March 1945: Commando Pigeon N.U.R.P. 38. E.G.U. 242. 'On three occasions, namely in June, 1942, August, 1942 and September, 1942, [Commando] was sent with agents into occupied France and on each occasion returned with valuable information on the day of release. The conditions under which the pigeon had to operate on two occasions were exceptionally adverse.' From the outbreak of the Second World War, civilian members of the National Pigeon Service supplied birds to the armed services to undertake a variety of tasks in support of the war effort. Many of the birds employed on military duties, especially in the early years, were trained racers and already experienced in flying home from Europe, especially from France and Spain. The role of the many pigeons employed during the Second War should not be underestimated; they made a significant contribution to news relay and to espionage. Pigeons took on a wide variety of tasks. Most aircraft flew with a pigeon to relay their position home in case of mishap as did some small allied naval craft; ground troops used them regularly to send back information both when operating from behind enemy lines or when pushing forward on major operations, as they did at Dieppe, the Normandy Landings and Arnhem. Pigeons carried messages, diagrams, photographs and plans; they carried photographic equipment for the surveillance of troop and armament movements; some were even used to disable enemy search lights when missions were in progress. Others were trained especially to accompany Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents on clandestine missions behind enemy lines. Recognising the importance of pigeons, SOE adopted them at an early stage in its history and first used them successfully in October 1940 to enable agents in enemy-occupied territory to communicate with the UK. Hugh Verity, who flew with a Special Duties Squadron as a 'pick-up' pilot, recounts an early 'practice flight' when two pigeons, parachuted into France with an agent, were each carried in a sock with the toes cut out, their heads poking through the hole (We Landed By Moonlight, Ian Allan, 1978, p.36). Pigeons played a vital part in the activities of SOE circuits formed in Europe. Moreover pigeons were used in all theatres of operation including the Middle East, Burma and Malaya, hence they had to fly not just long distances over oceans but also over deserts and jungles. These birds, therefore, provided a most valuable message and surveillance service and in so doing both saved lives and contributed to the effectiveness of military operations. For example, the information they brought back concerning the position of downed aircrews and small naval craft in danger led to successful rescues; it enabled the RAF to bomb essential German military installationss thus, on occasion, severely hindering the enemy's military effectiveness; and it saved the allies from mistakenly putting their own troops at risk of friendly fire. Furthermore the role of these birds as messengers with SOE prevented agents, civilian and military personnel behind enemy lines risking their own lives through having to maintain regular radio broadcasts. The year 1942 was a bleak time, with England, especially the south, being under threat from German bombardment by a variety of weapons. Contact with SOE agents and others in occupied Europe was very difficult due to the unreliability of the equipment and the fact that the Germans rigorously hunted down wireless operators, incarcerating, torturing and/or killing them and capturing their sets. Also radios parachuted in with agents were regularly lost or damaged on landing. What little news there was depended to a great extent on individuals prepared to risk their lives and on the significant contribution of the pigeon service. It was into this scenario that the pigeon named Commando was dropped, probably in a special container developed for that purpose. Commando (ring number NURP 38 EGU 242), a red chequer cock bird, was bred and trained as a homing pigeon prior to the Second World War by Mr S.A. Moon, Mounts Loft, Broadway, Hayward's Heath and already had experience in flying back home from Europe. He was one of many pigeons volunteered for service by his owner Sid Moon. Most of Sid's birds who made it back would have returned home to their Hayward's Heath loft, from where their vital messages, carried in small metal canisters strapped to their legs, were hurriedly transported to London or wherever the information was needed. The citation for Commando's Dickin Medal picks out three occasions on which he performed above and beyond the call of duty when in June, August and September 1942 he was parachuted into France with SOE agents and on each occasion he returned on the day of release with valuable information, twice operating in exceptionally adverse conditions. At the time of these operations Commando was about four years old. Of the many pigeons used by the military services, only 32 received the Dickin Medal. Commando and similar SOE birds were not asked to undertake routine or simple tasks, furthermore to become a recipient of the Dickin Medal they had to perform their already difficult duties to an exceptional standard. Pigeons differed in ability, stamina and determination to return. Additionally, the successful employment of these birds depended on the skills of their individual trainers. Hence it was only the very best birds that were suitable for the most hazardous and demanding operations and these birds often went on to complete numerous operations even after having been injured and wounded. Many did not return. It was not unusual for them to be expected to cover distances of several hundred miles. Of those parachuted into enemy territory it has been estimated that less than one in eight was successful in making it home. They died due to adverse weather conditions, having to fly distances that were too challenging, being killed by the enemy, or simply because they did not possess sufficient homing instinct. Some birds, dropped solo to be picked up by SOE circuits, local people and others, were never found and starved to death. The value of pigeons was recognised by the Germans who stationed marksmen and falconers along the Channel to try and bring down the birds (indeed the allies also took similar steps to counter the German use of pigeons). Of those that did return, flying at a rate of about one mile per minute, many arrived home covered in oil, exhausted or injured with broken bones and wounds. Although we do not have the flying histories of most of the pigeons who distinguished themselves, one for whom we do have some detail is Mary of Exeter, also a Dickin Medal recipient, which is illustrative of the conditions in which these birds operated. On several occasions she returned home wounded by pellets, once with half her wing shot away. It is recorded that she had to have 22 stitches put in her body at one time. Still she served for five years during which time she was shot at, attacked by hawks and brought down in a bombing raid. Commando's name appeared in the same Honours List as Royal Blue (the King's pigeon from the Royal Lofts, Sandringham) also awarded the Dickin Medal on account of his return from Holland in October 1940 as the first pigeon of the war to bring back a message from a force-landed crew. Both were presented with their awards by Rear Admiral R.M. Bellairs in London on 12.4.1945. After the war Commando appeared as part of a travelling exhibition organised by the Daily Herald, first staged in London, then Blackpool and possibly elsewhere. Commando was, apparently, still alive in 1947 as his photograph was published in the Homing World Stud Book. Sid Moon, a racing pigeon judge, had bred pigeons for more than 30 years on the outbreak of the Second World War and flew them in Crawley, Mitcham and Columbian Club races. In civilian life he was the proprietor of a gents outfitters, Broadleys, situated at a junction in the Broadway, Hayward's Heath (known as 'Moon's Corner' for many years after his death); it was over these premises that he maintained his pigeon loft. During the First World War he had been a Staff Sergeant in the Army Pigeon Service 1916-19, training pigeons in Ireland for use on the Western Front. At the start of the Second War he was coopted by the Air Ministry Pigeon Service until VE day and about 90 of his birds successfully delivered messages under varying degrees of danger and hardship, six were mentioned in the Meritorious Performance Listings and Commando, of course, received the Dickin Medal. Sid Moon died in 1958. The Dickin Medal was established in 1943 by Maria Dickin, founder of the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) to recognise conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty of animals and birds associated with or under the control of any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units. It is the highest award for animals and birds and is often referred to as 'the animal VC'. Awards are only made upon official recommendation. Since its inception, 60 Dickin Medals have been awarded (54 during the Second World War), 32 to pigeons, 24 to dogs, 3 to horses and 1 to a cat. Pigeons are prominently featured on a new memorial carved in Portland stone and bronze which is to be unveiled in Park Lane in November 2004 as a tribute to the very many thousands of animals that have served the UK in times of war. As only 60 Dickin Medals were awarded, they are rarely consigned for public sale. The only Dickin Medal awarded to a cat sold for an astonishing £23,100 in 1993. This was awarded to Simon the ship's cat on board HMS Amethyst, who was wounded when the ship was caught up in the Chinese Nationalist/Communist conflict in 1949 and held captive in the Yangtse River before making a successful dash down river for freedom. The last Dickin Medal to be sold at auction to an SOE pigeon was that to Mercury which in 1983 brought an equally unexpected £5000.

Sold for

£8,000