Auction: 25003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 7

(x) The historically fascinating Military General Service Medal awarded to Lieutenant A. F. R. de P. des Cars, who served as a subaltern in the 7th (The Queen's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars) during the Peninsular War - earning a unique combination of clasps to an officer of the Regiment in the process - and succeeded to the French Dukedom of Cars in 1825 before rising to senior rank in the French Army and commanding a Division in Algeria in 1830

Military General Service 1793-1814, 3 clasps, Corunna, Orthes, Toulouse (The Duke Descars, Lieut. 7th. Lt. Dgns.), upon its original silk riband, extremely fine

According to the Medal Roll compiled by Colin Message, this is one of only two examples of a Military General Service Medal officially named to a Duke, with the other being that to the Duke of Beaufort who, as Henry Somerset and a subaltern in the 10th Hussars, was an Aide-de-Camp to the Duke of Wellington.

The Roll further confirms award of these three clasps, and as such it is a unique entitlement to an officer of the 7th Light Dragoons (Hussars) - no other officers were entitled to (or lived to claim) the clasp for Corunna. Interestingly, only one further man of the 7th Hussars also received the Medal with this number and combination of clasps - one Private John Devreux; with a French-sounding surname, it seems fair to suggest that the latter may have been Orderly to the former.

Amédée-François-Régis de Pérusse des Cars was born on 30 December 1790 at Chambéry, Savoie, France, into a French Royalist family with a distinguished history: the Chateau des Cars had been the residence of the Pérusse's since at least the 12th century and counts several Medieval knights and even a great-grandson of King James II of England amongst their ancestors. As may be expected, with the worsening situation during the French Revolution, the family emigrated to England and young Amédée must therefore have been raised far from home. It is just as well they escaped, as the Chateau des Cars was pillaged by Revolutionaries before being sold for building materials - it stands as a ruin to this day.

At the age of 18, and using the anglicised name 'John Descars', he was commissioned Cornet (without Purchase) in the 7th (The Queen's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars), (London Gazette, 9 August 1808 refers): this suggests that, as a family with staunch Royalist leanings but perhaps little disposable income, the young man had the support of influential friends to secure him a commission, without payment, in such a socially prestigious regiment which often counted the Prince of Wales as a guest in the officers' Mess. Indeed, Frenchmen from noble families were far from unknown in the British Army at this time with another example of such being Antoine Geneviève Héraclius Agénor, Comte de Gramont (later 9th Duke of Gramont), who was only a year older than Amédée and would serve as an officer in the 10th (Prince of Wales's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars) in Portugal and Spain and owed his commission to the Prince's influence.

In October 1808, the Hussar Brigade (comprising the 7th, 10th and 15th Hussars) were ordered to Spain to join the army under command of Lieutenant-General Sir John Moore, with the overall objective of supporting the Spanish in their desire to rid Spain of Napoleon's forces. Distributed over a large number of transport ships, the Brigade arrived at Corunna piecemeal and took time to be re-assembled; the 7th commenced disembarkation on 9 November in less than ideal circumstances: ...'according to Vivian [Commanding Officer, 7th Hussars], the scene was 'truly deplorable'. It rained in torrents. Because the harbour was too full for them to be able to 'haul up on the quays, the horses were slung into the water and most of them obliged to swim on shore.' According to Hodge [Captain, 7th Hussars) 'Such a scene of confusion, disorder, and mismanagement was never witnessed.' Most of the horses had to swim as much as a quarter of a mile, which was 'rather hard' for them, coming straight from the 'hot hold'. Once ashore, in spite of the fact that the regiment's Quartermasters had been sent ahead to prepare quarters, nothing was ready for the horses and they stood shivering in the streets for hours...The men were soaked through, and many of them had been separated from their baggage and had no dry clothes to put on. The inevitable result was that they drowned their sorrows in the all too easily available wine. 'So much for our first day,' wrote Hodge' (The Prince's Dolls: Scandals, Skirmishes and Splendours of the Hussars, 1793-1815, John Mollo, p. 46-47 refers). Undoubtedly the same scene would have greeted a young aristocratic French officer amongst his British comrades - not an auspicious start for his first taste of active service.

From there, once all were assembled, Moore's army marched towards central Spain - the weather continued to be thoroughly miserable, which did no good to either men nor horses, especially as there was no time to rest and significant distances were covered every day. At the town of Villafranca, Cornet Phillips of the 15th Hussars was ordered back to the cathedral city of Lugo with all the Brigade's sick horses and men - no fewer than 170 of the former and 160 of the latter. It appears likely that John Descars (as he was known) was amongst this number, as whilst the Hussar Brigade was to defeat their French opponents at the battles of Sahagun and Benavente (21 and 29 December 1808 respectively) - clasp-earning actions - his entry on the Medal Roll for these battles notes: 'At Lugo'.

This may also have saved him from the terrible rigours and experiences of the Retreat to Corunna, carried out in the most appalling weather and over very inhospitable terrain. The horses and men suffered further from the lack of food, and it was a vastly reduced Hussar Brigade which finally reached Corunna and began to embark on 14 January 1809. At the Battle of Corunna (16 January 1809), Moore's army was successful in repulsing Marshal Soult's French force - but at the cost of his own life, he being mortally wounded by a cannonball towards the end of the day. Though, by this time, most of the Hussar Brigade were aboard their transports waiting to sail home and therefore did not participate in the battle, Descars was clearly present in some capacity - perhaps similarly to Colonel Robert Ballard Long who, until recently, had been Commanding Officer of the 15th Hussars and who unofficially attached himself to Moore's staff for the duration of the engagement. As if the past few months with its trials and tribulations and with a major battle at the end were not enough, the journey home was just as terrible as a major storm blew up which resulted in further tragic loss of life - indeed, the 7th Hussars suffered the worst casualties of the Brigade with 41 men lost in action and 56 drowned when their transport, the Despatch, struck rocks during the storm and foundered with the loss of all but seven men. Descars was again lucky to come through unscathed.

Promoted Lieutenant (again without Purchase, this time noted as 'John D'Escars') in 1809 (London Gazette, 25 February 1809 refers), it was to be several years until the Hussar Brigade saw active service again due to the lengthy process of recruiting men and obtaining new horses. Indeed, whilst the 10th, 15th and 18th Hussars returned to the Iberian Peninsula in early 1813 it was not until summer that year that the 7th caught up, with eight troops of the regiment embarking at Portsmouth on 15 August and arriving at Bilbao 15 days later. On their joining Wellington's army the Brigade Commander, Major-General Somerset, voiced his praise for their appearance and particularly that the officers seemed 'a very gentleman-like & smart set.'

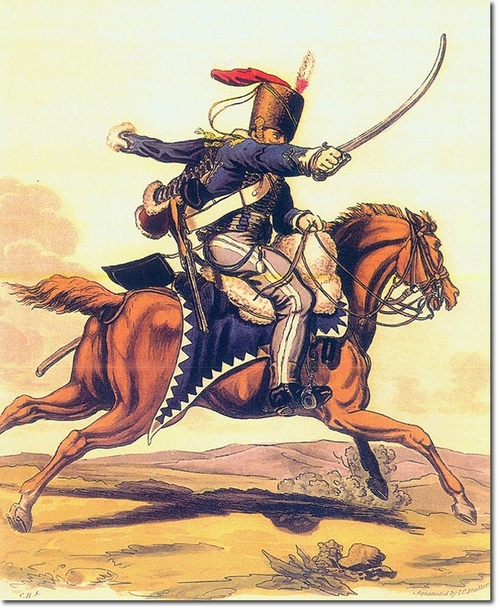

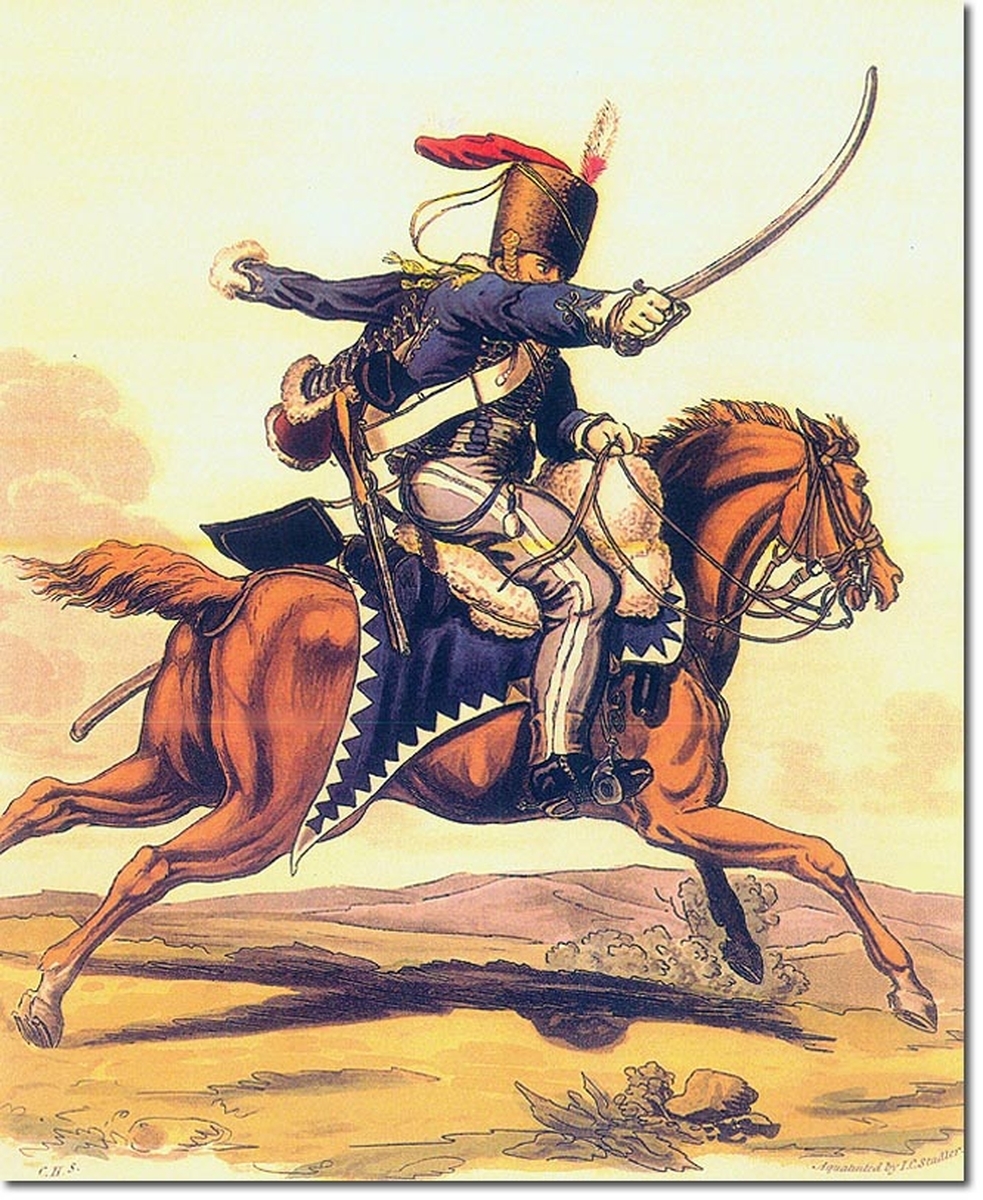

Being regiments of Light Cavalry, much of their time was taken on patrol and outpost duty where skirmishing with the French was common, especially as they were now being forced further and further out of Spain and into France by the efforts of Wellington's well-trained British-Portuguese-Spanish army: however, the 7th were given the opportunity to act as a formed unit in a major action at the Battle of Orthez on 2 February 1814 when, after sustained infantry assaults throughout the day, as the French began to retreat the regiment spotted a chance to charge their routing foe: Major William Thornhill led the attack, which was so effective the British cavalrymen overran two battalions of infantry at the loss of only three men killed and nine wounded, and apparently came very close to capturing one of the famous French 'eagles', so highly-prized as trophies of war. This charge was later immortalised in a stirring painting by the renowned military artist Denis Dighton.

As Wellington's army continued their advance the men of the Hussar Brigade resumed their duties on outposts and piquets, occasionally skirmishing with the French but otherwise seeing little action - indeed, at the final action of the Peninsular War (the Battle of Toulouse) on 10 April 1814, the 7th were present but not actively engaged. When Wellington entered the city two days later, he was met with great jubilation by a large number of French Royalists - it is not difficult to imagine Lieutenant Descars having similar thoughts and feelings at the final overthrow of Napoleon and the return to his homeland.

Later Life

Descars appears to have left the British Army shortly afterwards (either resigning or selling his Commission) but clearly enjoyed the life of a soldier - though specific details are lacking, he is noted as joining the French force known as 'The Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis' to participate in the 1823 expedition mobilised by King Louis XVIII to assist Spanish Royalists to restore King Ferdinand VII of Spain to absolute power. The expedition was a success, and on 30 May 1830 Amédée officially succeeded to the Dukedom of Cars. Shortly afterwards he participated in the campaign to conquer Algeria as commander of the 3rd Division under the overall command of General de Bourmont. His troops saw plenty of action, as de Bourmont's official despatch later recounted:

'To His Excellency the President of the Council of Ministers.

Camp before Algiers, July 1.

...The Duke d'Escars received orders to attack on the left with the first two brigades of his division, and to follow nearly the line of separation between the two ravines which run to the each and west of Algiers. It was on this side that the enemy had assembled his greatest force. The brigades of Berthier and Hurel used in the attack as much vigour as they had shewed constancy and coolness in the defensive position which they had occupied on the preceding days. Being broken by them, then enemy did not wait the shock on the other points, and on all sides they took to flight.

The division of Berthezene changed its direction, and proceeded to occupy the crest of the heights which rise between the sea and the point of attack of the division of d'Escars; these heights command all the neighbouring country...the Duke d'Escars immediately approached the Emperor's Fort, in order that the two brigades might be enabled to combine the very next night in opening the trenches...in the action of the 29th, we had forty or fifty men killed or wounded. The enemy left many dead on the field of battle. A flag and five pieces of cannon were taken.'...

I have the honour, &c.

Lieut.-Gen. Peer of France, Commanding in Chief

the Army of the African Expedition,

Count de Bourmont.' (Morning Advertiser, 17 July 1830, p. 2 - 3 refers).

When news of the July Revolution of 1830 reached Algeria, des Cars returned to France and then accompanied the recently-deposed King Charles X into exile in Britain; he later returned to France, and died at Cannes on 19 January 1868 at the age of 77. On 25 June 1817 he had married Augustine du Bouchet de Sourches de Tourzel and from 1819 - 1836 went on to have issue of three sons and three daughters: the title is still extant and currently held by Louis-Amédée de Pérusse des Cars, 8th Duke of Cars.

Sold together with a copied Medal Roll extract and the original forwarding letter for his Military General Service Medal, dated 6 February 1849, addressed to 'Le Duc Descars, formerly Lt. 7 Hussars'. This with a tear and damage at right-centre, but undoubtedly a very rare and remarkable survivor.

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£5,000

Starting price

£2800