Auction: 22103 - Orders, Decorations and Medals VII - e-Auction

Lot: 656

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'I went below again and found a second shell had come through into the boys' mess deck, through the embrasure overhead. Smoke was pouring out of the wet provision room and seeing Pring leaning up against a bulkhead told him to flood it. He seemed dazed and silly and I 'bit' him for not getting on quicker. I didn't know at the time he was very badly hit, anyway he did the job before he was too far gone. Looked through the hole in the armour of our boys' mess deck, it looked red, lurid and beastly, heavy firing all around and splashes everywhere …

The decks were all warped and resin under corticene crackling like burning holly. The upper deck and superstructure looked perfectly awful, holed everywhere. I think at this time the firing has slackened, but the noise was deafening, shells bursting short threw tons of water over the ship. The superstructure itself was in an awful state of chaos. Port shelter completely gone and the starboard side had several big holes in it, everything wrecked and it looked like a burnt out factory, all blackened and beams twisted everywhere …'

Telling testimony to the damage caused H.M.S. Warspite at Jutland and the gallant conduct of Chief Stoker George Pring; in the words of Warspite's second-in-command, Commander H. T. Walwyn, D.S.O., R.N.

The outstanding and well-documented Great War Battle of Jutland C.G.M. group of six awarded to Chief Stoker W. M. Pring, Royal Navy, who was present aboard the battleship H.M.S. Warspite on that memorable occasion

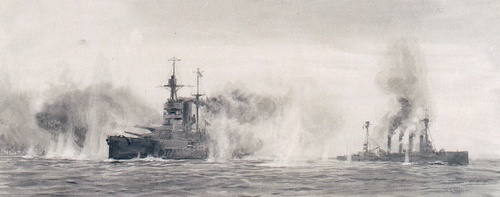

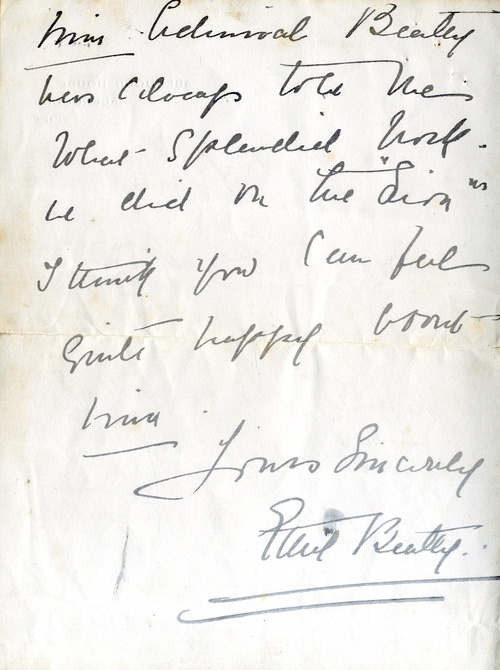

The punishment meted out to Warspite after her steering jammed - sending her round in circles 'like a kitten chasing its tail'- is the stuff of legend: singled out and pulverised by the combined armament of some 20 enemy ships, she was hit by at least 15 heavy calibre enemy shells and sustained casualties of 14 killed and 32 wounded

Among the latter was William Pring, who suffered a severe abdominal wound from a shell splinter: concealing the serious nature of his wound, he continued with grim determination to undertake important damage repair duties amidst scenes of terrible carnage

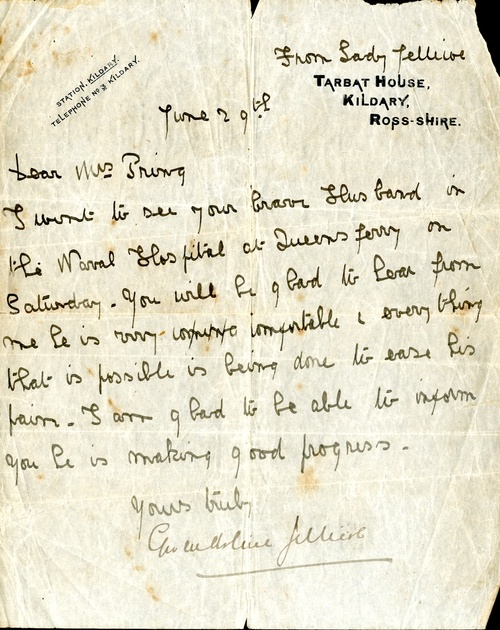

Much impressed and moved by his stoicism and gallantry, Lady Gwendoline Jellicoe and Lady Ethel Beatty paid their respects to him at the Naval Hospital at Queensferry, both writing to reassure his wife that her husband was making good progress

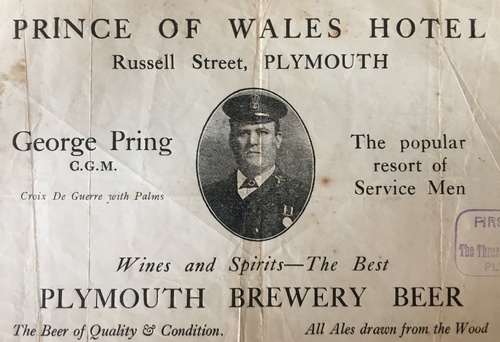

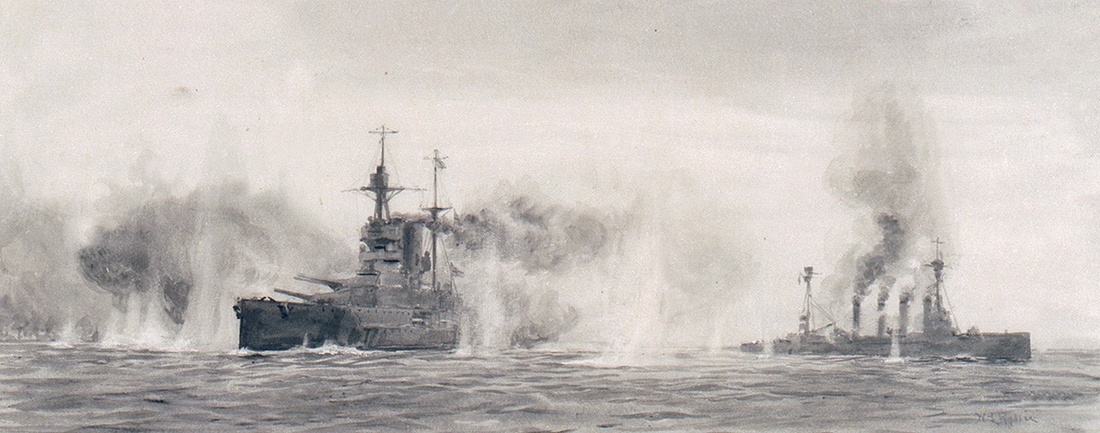

Formally 'invalided ashore' on account of his wounds in August 1916, Pring afterwards became the landlord of the Prince of Wales Hotel in Russell Street, Plymouth and, appropriately enough for such a gallant seadog, excelled as a bowls team captain, playing on the Hoe made famous by Sir Francis Drake

Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, G.V.R. (131173. W. G. Pring, Ch. Sto. H.M.S. Warspite. 31. May,-1. June, 1916.); 1914-15 Star (161176, W. J. Pring, Ch. Sto., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (161176 W. G. Pring. Ch. Sto. R.N.), with M.I.D. oak leaves; Naval L.S. & G.C., E.VII.R. (161176 W. G. Pring, Ch. Sto., H.M.S. Commonwealth.); France, Republic, Croix de Guerre, with Palme, mounted as worn in two parts, minor edge bruise to first, overall good very fine (6)

A total of 15 Conspicuous Gallantry Medals were awarded for Jutland.

C.G.M. London Gazette 15 September 1916.

'Although severely wounded in the action, he continued to carry out important duties with repair parties until the action was finished.'

William George Pring was born at Plympton, Devon on 7 June 1872 and entered the Royal Navy as a Stoker 2nd Class in June 1891. Gaining rapid advancement, he was appointed a Chief Stoker in November 1901 and was awarded his L.S. and G.C. Medal in the summer of 1906.

An accompanying newspaper obituary states that he was serving in H.M.S. Decoy, 'when she ran ashore on the Wolf Lighthouse, and had a narrow escape from drowning'. He also served under Admiral Beatty in the Lion in the lead-up to hostilities, the latter commenting to his wife on Pring's 'splendid work' aboard his flagship.

On the outbreak of war in August 1914, he was employed at a shore establishment but in April 1915 he joined the ship's company of the Queen Elizabeth-class battleship Warspite and, as cited above, he was subsequently present in her as part of the 5th Battle Squadron (5 BS) at the battle of Jutland.

Jutland

Commanded by Captain E. M. Philpotts, R.N. - and boasting her prescient motto 'I Despise the Hard Knocks of War' - Warspite's armoury included four twin 15-inch guns. She was of revolutionary design and capable of 24 knots, even with her robust armoured plating which in the 'vitals' was 13-inches-thick.

Quite a few eye-witness accounts of Warspite's part in that famous battle survive, but by way of summary of her experiences the following extract is taken from Chris Bilham's The Jutland Honours (Spink, 2020):

'At 14:30 hrs on 31 May 1916 5 BS was five miles astern of Lion, and had just commenced a turn to the north to rendezvous with Jellicoe, when the enemy was sighted. Lion immediately executed a turn to the south-east, at the same time signalling by flag for the other ships to do so. However, because of the distance and the heavy smoke produced by the battle-cruisers when travelling at speed, Lion's signal was not seen. Therefore, although Admiral Evan-Thomas, commanding 5 BS, saw the battle-cruisers turning away, he assumed that Beatty wanted him to maintain the course he was on. It was nearly ten minutes before Beatty noticed that 5 BS was not following and signalled Evan-Thomas to join him; by that time, the distance between the two groups of ships was ten miles. Beatty could still have slowed down to allow time for 5 BS to join him but it was not in his nature to do so when the enemy was in sight and so the Battle Cruiser Fleet went into action at 15:45 with only six capital ships instead of ten. This was one of the critical errors which cost the British a decisive victory.

By 16:10 hrs 5 BS was within range of the rear-most ships in the German line and opened fire at the extreme range of 19,000 yards. Fresh from their training under Jellicoe's meticulous eye, it was one of the most accurate-shooting squadrons in the Grand Fleet and soon 15-inch shells were raining down on the German ships. Von der Tann and Moltke were both hit and suffered serious damage. Admiral Scheer wrote 'Superiority in firing and tactical advantages of position were decidedly on our side until 4:19 pm when a new unit of four or five ships of the Queen Elizabeth type, with a considerable surplus of speed, drew up from a north-westerly direction and … joined in the fighting. It was the English 5th Battle Squadron. This made the situation critical for our battle-cruisers. The new enemy fired with extraordinary rapidity and accuracy'.

At this stage of the battle, known as 'The Run to the South', Hipper and the German battle-cruisers were luring Beatty and his ships towards the main German battle fleet, approaching from the south. Every ninety seconds brought the British one mile closer to the sixteen dreadnoughts of the High Seas Fleet.

At 16:35 the British light cruisers reported the presence of the High Seas Fleet to Beatty, who continued on his south-east course for two more minutes until he could see the masts of the German battleships twelve miles away. Then, at 16:40 hrs, the battle-cruisers reversed course to the north-west. Now the roles had changed, and Beatty was luring the Germans towards Jellicoe and the guns of the Grand Fleet, still more than 40 miles to the north. This phase of the battle, which lasted for about an hour, is referred to as 'The Run to the North'.

When the battle-cruisers changed course, another communications error occurred and the order was not passed to 5 BS until 16:57, fully a quarter of an hour after Lion had done so. With the two fleets steaming towards each other at full speed this was enough time to bring 5 BS well within range of the High Seas Fleet. To compound the error, the ships were ordered to turn in succession, rather than together; the Germans concentrated their fire on the turning point and Warspite was hit three times. As 5 BS carried out its belated turn, an officer in Malaya observed 'that our battle cruisers, proceeding northerly at full speed in close action with the German battle cruisers, were already quite 7,000 or 8,000 yards ahead of us. I then realised that just the four of us of the 5th BS alone would have to entertain the High Seas Fleet - four against perhaps twenty. The enemy continued to fire rapidly at us during and after the turn'.

Warspite and her sisters formed the rear-guard of the Battle Cruiser Fleet. Warspite and Malaya concentrated on the leading ships of the High Seas Fleet while the other two fired on the rear-most German battle cruisers. Warspite's Executive Officer wrote 'Very soon after the turn I saw on our starboard quarter the whole of the High Seas Fleet-masts, funnels and an endless ripple of orange flashes all down the line… I distinctly saw two of our salvoes hit the leading German battleship. Sheets of yellow flame went right over her masts and she looked red fore and aft like a burning haystack. I know we hit her hard.'

Warspite and Malaya obtained a number of hits on Konig and two other battleships, but were themselves hard hit. This was the most dangerous stage of the battle for Warspite; if there had been any damage to her propulsion machinery she would have fallen behind to be destroyed by an over-whelming force of the enemy, as happened to Blucher at the Dogger Bank. Warspite's Executive Officer was sent to inspect the damage and Gordon comments 'His 26 page narrative of his between-decks steeplechase around the battleship's accumulating scenes of carnage - with its terse references to fire, smoke, darkness, chasms awaiting the unwary, escaping steam, electrical shocks, flooding, terrible injuries and incidental absurdities - provides a nightmare glimpse of the realities of modern naval action'.

The 'Run to the North' came to an end at about 18:00 when the Battle Cruiser Fleet sighted the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe then executed a complicated manoeuvre, changing from cruising formation (in columns) to a single line of 24 battleships. 5 BS attempted to form astern of the others but, at this critical juncture, Warspite's helm jammed and she found herself charging the enemy fleet alone. She closed to within 12,000 meters of the enemy line and was hit by at least seven heavy calibre shells. Her Captain decided to continue the turn to starboard and completed two full circles before recovering control of his ship. Warspite's bizarre manoeuvre at least had the beneficial effect of drawing off fire from the crippled armoured cruiser Warrior, enabling her to escape.

At this stage, severely damaged and with unreliable steering gear, Warspite was ordered to return to Rosyth. Even then, she was not out of danger; at 09:35 on the morning of 1 June, she observed two torpedoes which passed close to the ship, one on either side, and there were two more encounters with submarines before she finally docked at 15:15 hrs. Considering the damage she had sustained, her casualties were remarkably light: fourteen men killed and thirty-two wounded. She stayed in dock until 4 July.'

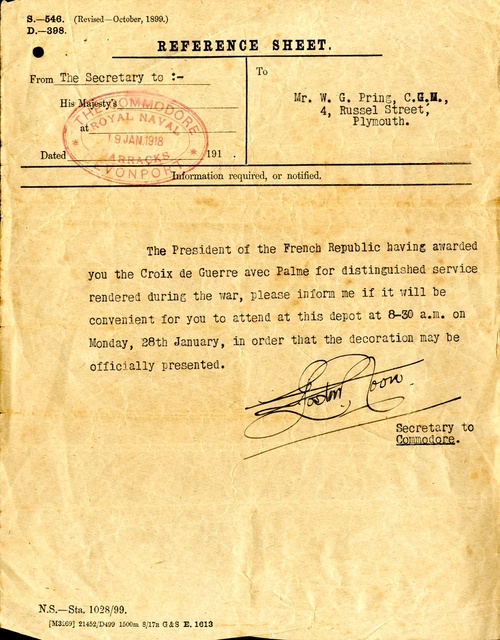

As stated above, Pring was admitted to the Royal Naval Hospital at Queensferry, where he was visited by Lady Gwendoline Jellicoe and Lady Ethel Beatty. Having been formally 'invalided ashore' in August 1916, he attended two investitures at Devonport, where he received his C.G.M. and French Croix de Guerre.

Postscript

Then, as recounted by a newspaper obituary, he settled down to a new life as Landlord of the Prince of Wales Hotel in Russell Street, Plymouth. The same source states:

'He was a keen and expert bowler, and for several seasons was the captain of the Hoe Bowling Club. He had also played for his county on many occasions, indeed, his last game this summer was for Devon. Mr. Pring was also a supporter of Plymouth Argyll Football Club.'

He died in Plymouth in November 1931.

Sold with an impressive archive of original documentation, including:

(i)

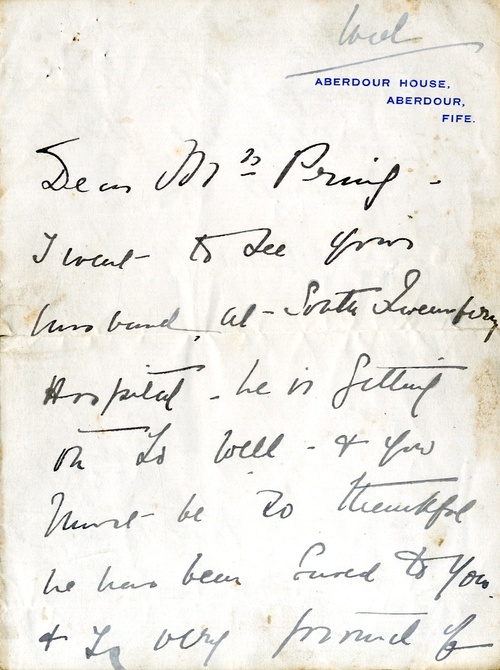

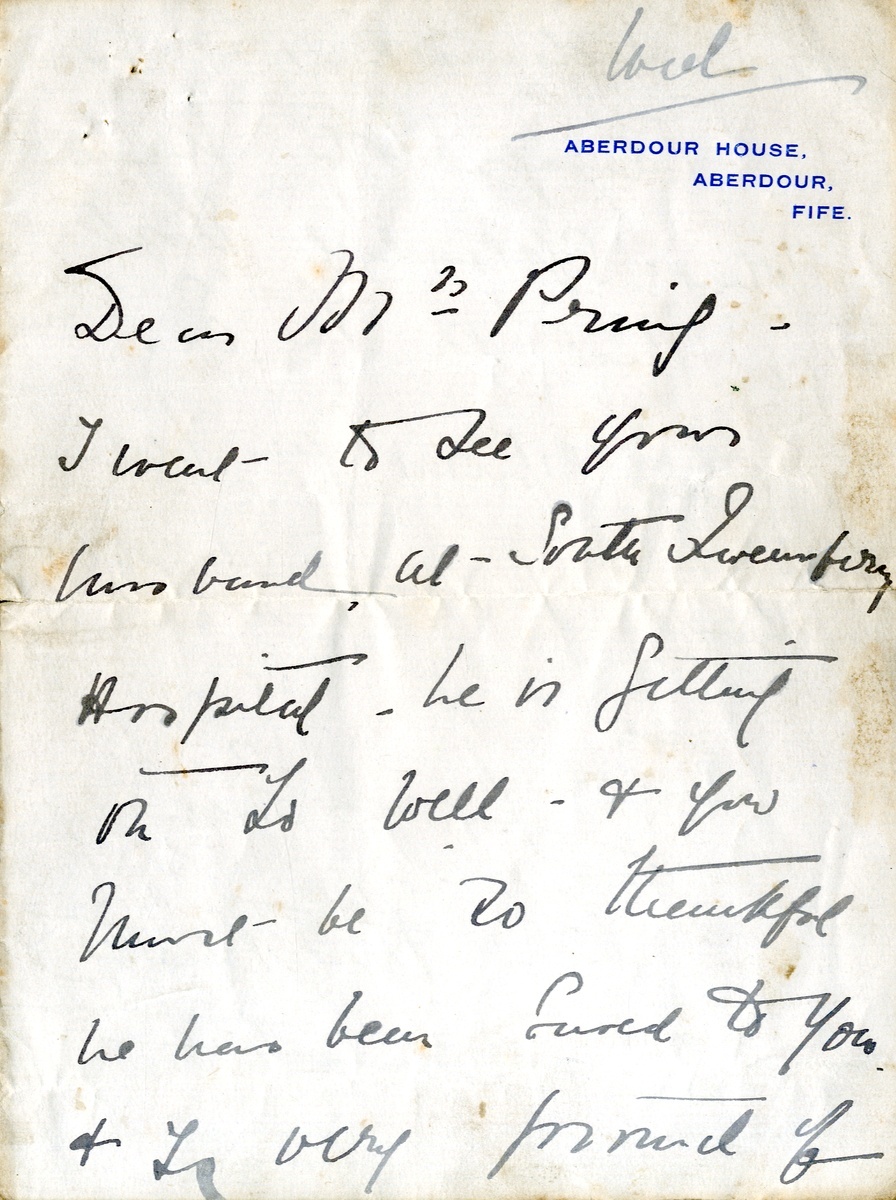

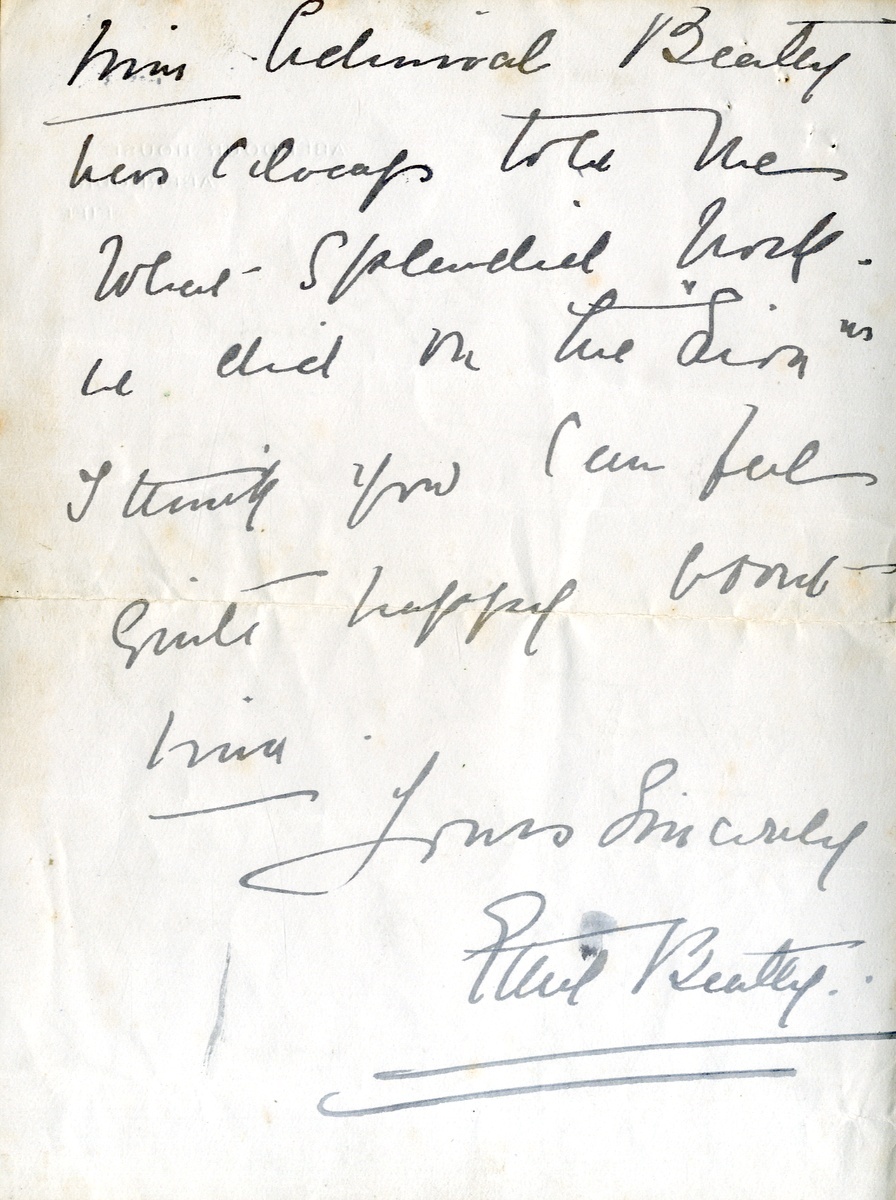

A handwritten letter from Lady Ethel Beatty to the recipient's wife, undated, on Aberdour House, Fife notepaper, in which she reports having visited him in hospital, where 'he is getting on so well and you must be so thankful that he has been saved to you … Admiral Beatty has always told me what splendid work he did [earlier] in the Lion …'

(ii)A telegram from Lady Ethel Beatty to the recipient's wife, dated 7 June 1916, reporting that 'he was getting on well and is cheerful. You must be very proud of him …'

(iii)

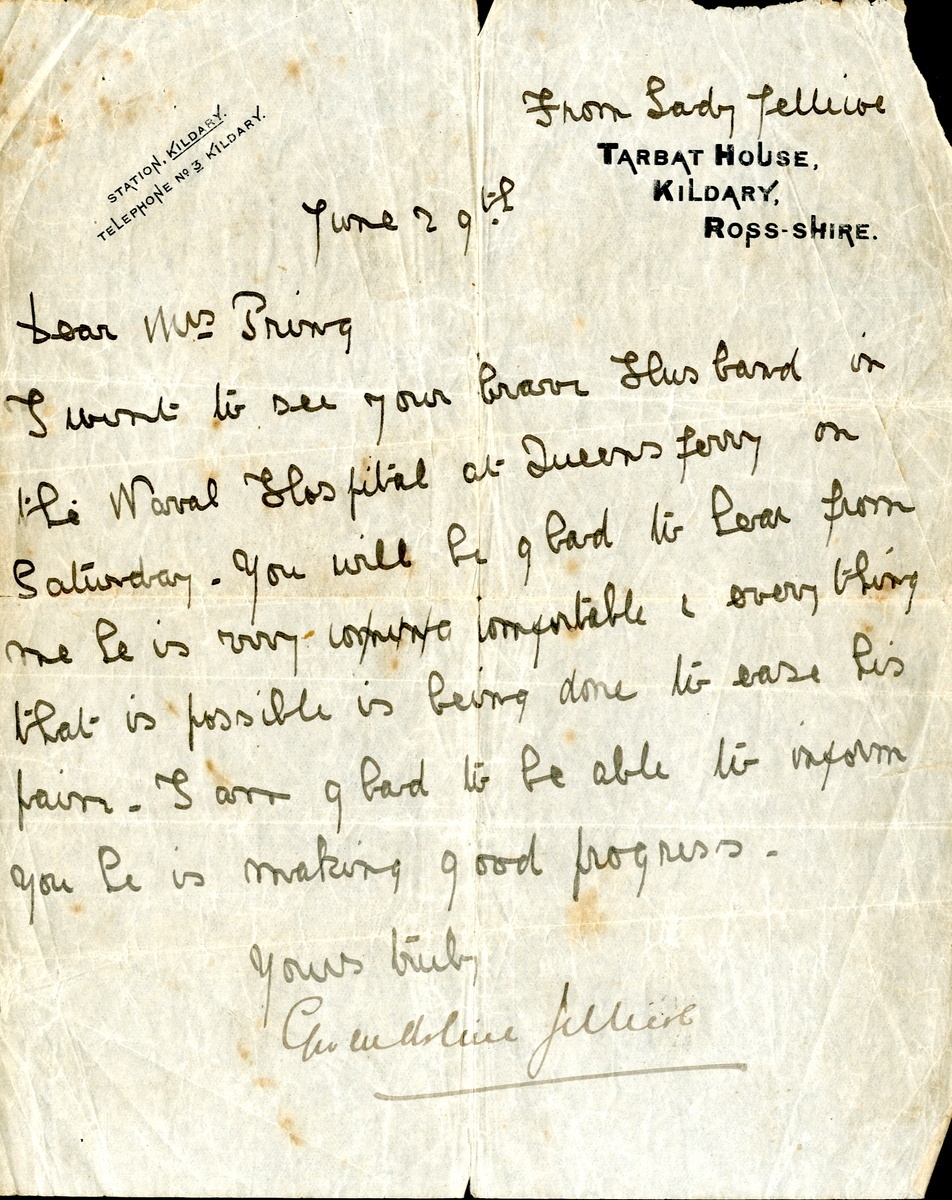

A handwritten letter from Lady Gwendoline Jellicoe to the recipient's wife, dated 29th June [1916], on Tarbat House, Kildary, Ross-shire notepaper, in which she reports having visited him in hospital, where 'everything that is possible is being done to ease his pain …'

(iv)

A handwritten letter from temporary Surgeon A. L. Pearce Gould, R.N., to the recipient, dated 8 November 1916 at the Royal Naval Hospital, Plymouth, in which he states it was no longer possible to get him a place at the Naval Convalescent Home at Chatsworth since he has been discharged the service, but as requested was enclosing a prescription - 'I feel sure that the attacks you have been suffering from will become steadily less frequent …'; said prescription included with letter

(v)

Admiralty letter to the recipient, dated 23 November 1916, informing him of a £10 annuity to accompany the award of his C.G.M., to 'commence from the date of the action for which the Medal was awarded (i.e. 31st May 1916)'; together with another Admiralty letter, dated 25 August 1921, forwarding the recipient a length of C.G.M. riband, as per the new design of white, with blue narrow edges.

(vi)

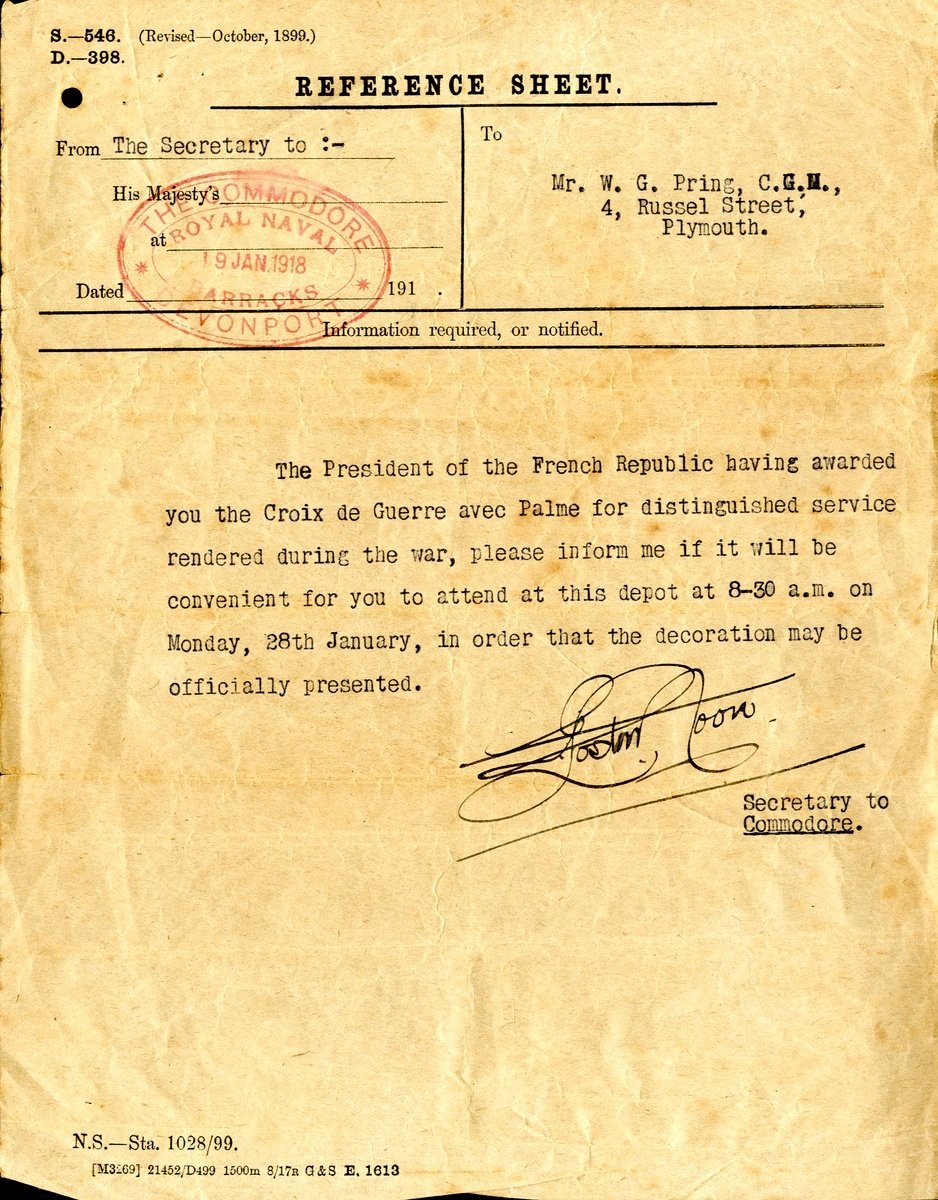

A message from the Commodore, Royal Naval Barracks, Devonport, dated 19 January 1918, requesting the recipient's presence to be 'officially presented' his Croix de Guerre at the barracks on the 28th; together with an Admiralty letter, dated 14 June 1918, forwarding the recipient his 'diploma of the Croix de Guerre awarded to you by the French Government.'

(vii)

His Silver War Badge certificate (No. 4462), in the name of 'William George Pring, late Chief Stoker, ON 161176'

(viii)

A quantity of documentation appertaining to the recipient's career as Landlord of the Prince of Wales Hotel in Russell Street, Plymouth, including letters, invoices and receipts, etc., including his certificate of registration as a Licensed Retailer, dated 22 April 1918.

(ix)

A number of newspaper articles relating to the award of the C.G.M. and the recipient's life and career after the war, including lists of honours awarded during the battle, an article on the award of medals at Davenport with the recipient's specifically highlighted and an obituary covering his life and career.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£16,000

Starting price

£7000