Auction: 22001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 601

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'The most striking thing about the citation is the cool, calculated bravery. Scarf sized up the situation and decided that for the good of the Squadron and the Service his sortie was necessary.

Having decided that, he had a measure of time to think on his way to the target. Many of us might have had the temptation to turn back. Scarf resisted that temptation, completed his task and died of his wounds.

I would put his V.C. among the class of individual awards for the submarine attacks on the Tirpitz.'

Air Vice-Marshal Combe on Scarf.

'Your late husband did a wonderful act, for which his country will be eternally grateful.'

H.M. The King, upon presenting the Victoria Cross to Sally Scarf at Buckingham Palace, 30 June 1946.

The historically important and unique posthumous 'Battle of Malaya' V.C. group of five awarded to Squadron Leader A. S. K. 'Pongo' Scarf, No. 62 Squadron, Royal Air Force

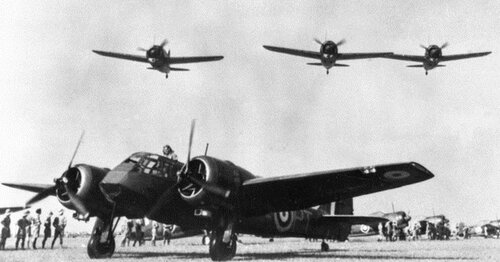

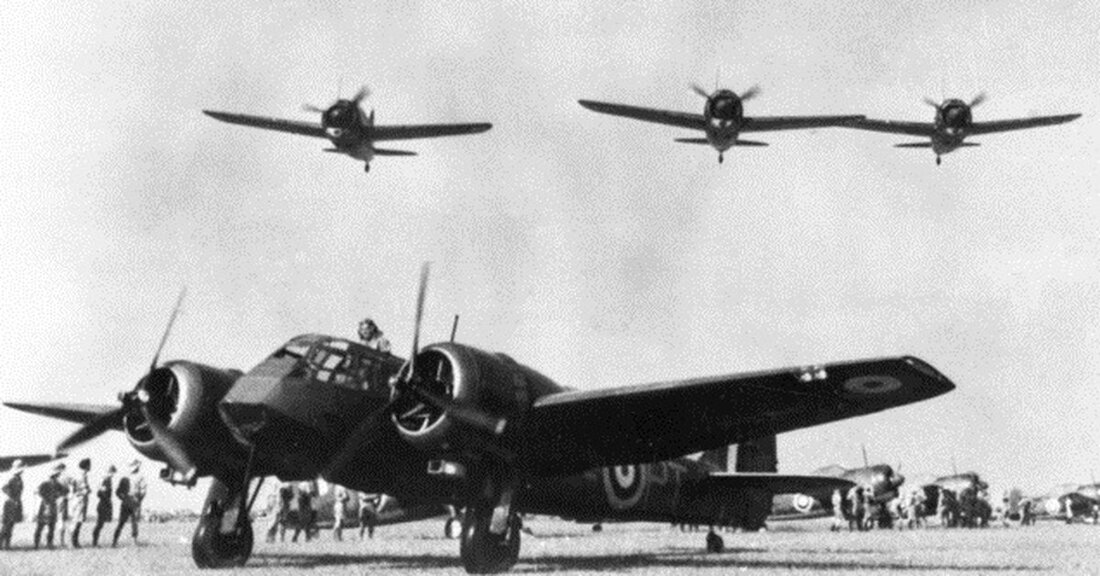

Joining the Royal Air Force in 1936, by December 1941 Scarf was in Command of his Squadron who were flying Blenheims close to the Malay-Thai border when the relentless Japanese attacks were unleashed; having hurriedly moved to Butterworth airfield, the requirement to stem the rapid advancement and devastating aerial bombardments coming out of Singora saw Scarf take to the air: he could do nothing as he saw every single Blenheim in his Flight be shot up before they could even get 'wheels up'

So the responsibility fell squarely on his shoulders to make the daring raid alone and without fighter support; Scarf made his bombing run despite being constantly harassed but was mortally wounded on the return journey, having his left arm shattered and several holes in his chest and back

Somehow, with the assistance of his two Sergeants - and barely conscious - Scarf kept pressure on the controls despite his shattered arm and managed to crash-land at Alor Star, being rushed to the hospital and swiftly being administered morphia and two pints of blood donated by a Nurse who was a blood match; that Nurse turned out to be his wife, whom he had only been married for a few months, she was carrying their unborn child

Scarf slipped away whilst in surgery but in the chaos of the Battle of Malaya - and eventual Fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942 - it would be over four years until his widow would be presented with the Victoria Cross by The King which her late husband had duly earned - his was truly the V.C. that represented the 'Forgotten War'

Victoria Cross, reverse of the suspension bar engraved 'S/Ldr. A. S. K. Scarf. 62 Sqdn. R.A.F.', the reverse of the Cross engraved '11 June, 1946.'; 1939-45 Star; Pacific Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, nearly extremely fine (5)

V.C. London Gazette 21 June 1946:

'On 9th December, 1941, all available aircraft from the Royal Air Force Station, Butterworth, Malaya, were ordered to make a daylight attack on the advanced operational base of the Japanese Air Force at Singora, Thailand. From this base, the enemy fighter squadrons were supporting the landing operations.

The aircraft detailed for the sortie were on the point of taking off when the enemy made a combined dive-bombing and low level machine-gun attack on the airfield. All our aircraft were destroyed or damaged with the exception of the Blenheim piloted by Squadron Leader Scarf. This aircraft had become airborne a few seconds before the attack started.

Squadron Leader Scarf circled the airfield and witnessed the disaster. It would have been reasonable had he abandoned the projected operation which was intended to be a formation sortie. He decided, however, to press on to Singora in his single aircraft. Although he knew that this individual action could not inflict much material damage on the enemy, he, nevertheless, appreciated the moral effect which it would have on the remainder of the squadron, who were helplessly watching their aircraft burning on the ground.

Squadron Leader Scarf completed his attack successfully. The opposition over the target was severe and included attacks by a considerable number of enemy fighters. In the course of these encounters, Squadron Leader Scarf was mortally wounded.

The enemy continued to engage him in a running fight, which lasted until he had regained the Malayan border. Squadron Leader Scarf fought a brilliant evasive action in a valiant attempt to return to his base. Although he displayed the utmost gallantry and determination, he was, owing to his wounds, unable to accomplish this. He made a successful forced-landing at Alor Star without causing any injury to his crew. He was received into hospital as soon as possible, but died shortly after admission.

Squadron Leader Scarf displayed supreme heroism in the face of tremendous odds and his splendid example of self-sacrifice will long be remembered.'

26 awards of the Victoria Cross to the Royal Air Force to date, of which exactly half of them awarded posthumously. A unique award to the Royal Air Force for this theatre of war.

4 awards of the Victoria Cross for the Battle of Malaya, this the first by date of action.

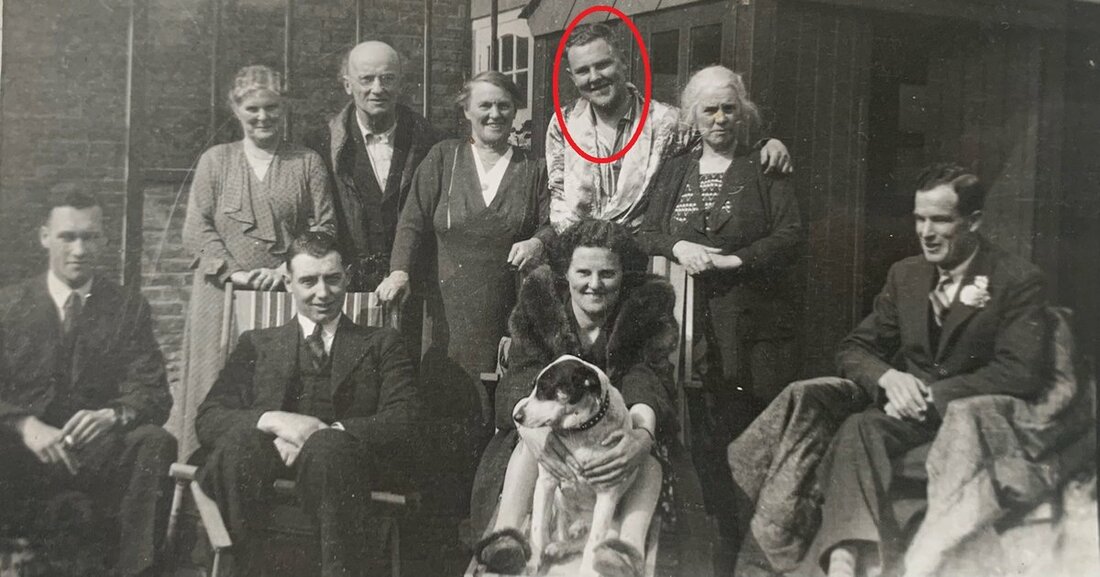

Arthur Stewart King Scarf - or "Pongo" to his friends and comrades - was born at Wimbledon, London on 14 June 1913 and was educated at King's College School in Wimbledon, being a keen but average rugby player for the 2nd XV but excelling as a rower. Indeed, he took the Staines Regatta, in the stroke seat, in the Kingston VIII in 1934 - something of an unexpected victory in the final against the London Rowing Club. A failed application - the result of less than favourable school results - to enter the Royal Navy followed shortly after.

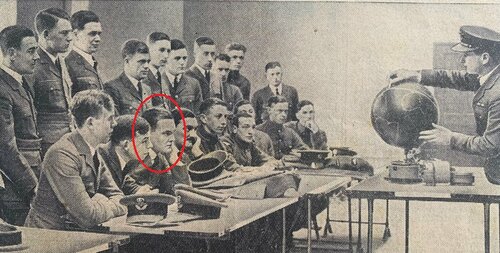

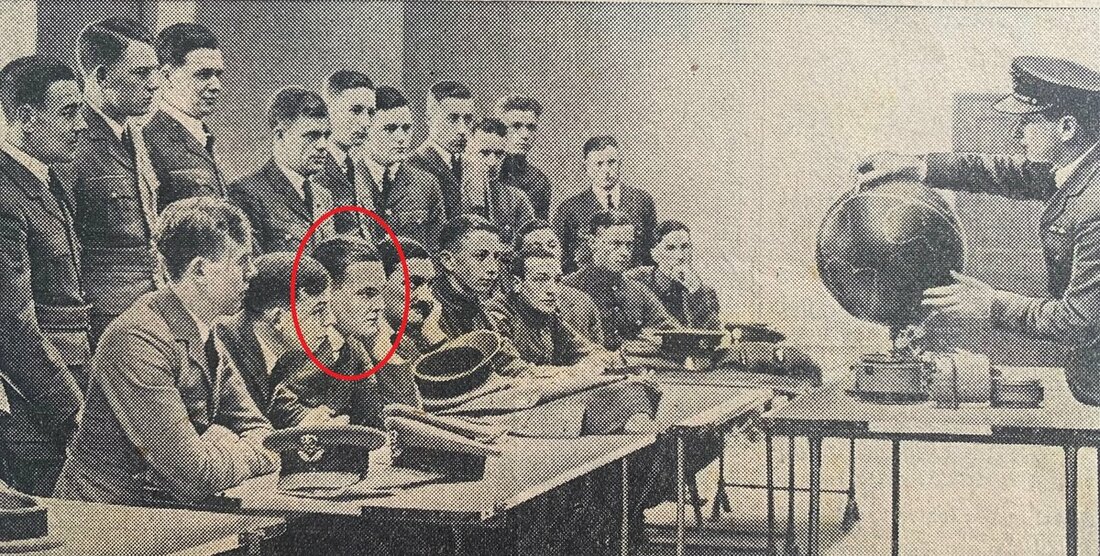

Pongo - noted as having been '...obsessed with aeroplanes' as a schoolboy - thence went up to RAF Cranwell in 1936. Gaining his 'Wings' in October 1936, he was posted to No. 9 Squadron at Scampton, operating the Handley Page Heyford. In 1937 he transferred to No. 62 Squadron, a light bomber unit which received the Bristol Blenheim in February 1938. Just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the Squadron was detached to bases in northern Malaya. Whilst there, he joined Frank Griffiths (later a Group Captain) and Ken Hutchings (killed towing a glider on D-Day) on a cruise up the Malacca Straits on a yacht. In Angel Visits - from Biplane to Jet, he related a few tales of him:

'It is said that there are seven qualities required of a Pilot which no written exam can reveal. They are sense of responsibility, leadership, anticipation, resourcefulness, hardihood, courage and ability to get on with people.

Pongo possessed all these qualities and more but maintained a facade which delighted his friends and irritated his seniors for he pretended that he was a bit 'dim' and that all orders, complex navigational problems and technicalities of aircraft were beyond him. It was all an act as his peers well knew. He was however unlucky at times which gave his seniors the impression that he didn't take life seriously enough.

He was frequently late for lectures and generally made morning parades by the skin of his teeth dashing on to the parade ground just as the command 'Fall in the Officers' was given.

He did this on one formal parade. Prayers were said and then the Station Commander left the saluting base to carry out his inspection to find Pongo standing stiffly to attention, immaculately turned out but instead of his regulation service black tie he was wearing a Richmond Rowing Club tie! A late night party, no breakfast and dressing in too much of a hurry caused this peccadillo.'

Pongo married Elizabeth 'Sally', a Nurse, in Penang in April 1941.

Battle of Malaya

From July 1941, No. 62 Squadron was based at Alor Star near the Thai border and at the outbreak of hostilities with Japan in December 1941 the Squadron came under heavy air attack. The Battle opened in earnest on 8 December 1941 and followed the strike on the American Fleet at Pearl Harbour the previous day. The Malayan campaign began when the 25th Army, under the command of Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita, invaded Malaya on 8 December 1941. Japanese troops launched an amphibious assault on the northern coast of Malaya at Kota Bharu and started advancing down the eastern coast of Malaya. That day also saw the first air raids on Singapore itself, whilst Scarf and his comrades were heavily engaged by the enemy. That day the airfields at Singora and Patani - just over the border in Thailand - gave the Japanese the perfect bases from which to launch strike raids.

No. 62 Squadron, together with No. 27 & 34 Squadrons were withdrawn to RAF Butterworth in order to re-group and prepare for the battle ahead. The air base had been swiftly completed and opened in October 1941, shortly before the invasion and was based in the city of Seberang Perai, Penang. It lies about 3km east of George Town, the capital city of Penang, across the Penang Strait. As 9 December dawned, the airfield came under attack from aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service and suffered damage from the Mitsubishi G3M and G4M bombers. Obsolete Brewster Buffalo fighters from No. 21 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, based at the airfield took to the air to engage the escorting Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters. They suffered heavy losses against the highly trained and experienced Japanese fighter pilots and most couldn't even get themselves in the air as the enemy swarmed for their stinging attacks.

It was imperative that the bombers got themselves airborne, firstly to prevent themselves being destroyed on the ground, but also to attempt to stem the advances of the Japanese. The first wave of six aircraft somehow got up at 1200hrs. Three were lost but three made it home. At 1700hrs it was the turn of the remainder of No. 62 Squadron and the three survivors of the first wave to take to the skies. Pongo was at the head of his Squadron, in Blenheim L1134 FX-F, with Flight Sergeant (later Squadron Leader) Paddy Calder and Flight Sergeant Cyril Rich with him as crew. Making for the runway, Pongo saw the enemy coming in for their own attack. He got airborne just as the enemy made their bombing run and was the only aeroplane of the second wave to get into the sky. It was at this point, circling to view the horrific scenes below him, that he made the cool, calm decision to make his attack alone and without support. He answered the call of duty and made the 30-mile flight across the border for Singora. As recalled in the citation for his Victoria Cross, Pongo was harrassed the whole way into his attack, surely knowing it would cost him his life.

Having made his attack on Singora to good effect, the enemy were, in the words of Rich '....lined up like Taxis.'

As the bombs were released and Rich opened up with his own guns, the fighters narrowed in on the lone bomber. Pongo was mortally wounded as the two ranks of six fighters tore into them. The fact that he managed to get back to Alor Star to crash land - without loss of life to either of his crew - is simply remarkable. They were struck by cannon and machine-gun fire at ranges down to 200ft and it would be fate that the left-handed Pongo would have his left arm shattered. As the fatal shots struck him, he collapsed and the aeroplane went into a shallow dive. Calder rushed to him in order to try to help and it took Rich to hold him in his seat before they realised he was still just conscious and had never released his grip on the controls. Pongo gave a nod and continued to steer them south, to safety and across the border, at which point the enemy fighters fizzled away.

Coming into 300ft altitude, Pongo put her down and slithered the aircraft across a paddy field which took them to within a stones-throw from the Hospital.

The final few hours of his life are perhaps the most poignant part of this story. Losing blood rapidly, he was rushed into the Hospital at Alor Star and given some relief via morphia. His wife Sally, who had become pregnant in the few happy months the newly-married couple had shared together, had volunteered to Nurse at that place in order to be closer to her husband. In her own words:

'On the 9th December 1941, during the afternoon, I was off duty when Pat Boxall, another Nursing Sister at Alor Star Hospital came over to tell me an English casualty was being brought in.

I was very shocked to find it was my late husband Pongo who by some miracle managed to land his plane in a paddy field nearby to the aerodrome and hospital, his two Sergeants being unscathed.

Dr Peach who brough him in and administered some medication and Pongo was cheerfully saying "Dont Worry", but he was severely wounded in his left arm and back. He was quietly settled in a twin bedded ward and a saline drip was put up. As soon as the Doctor saw him he ordered at least two pints of blood. As I was found compatible, two pints were taken.

Pat Boxall went with him to the theatre. Pongo was still cheerful and said "Don't worry, keep smiling, chin up!"

Pat returned soon afterwards to tell me he just slipped away whilst under anaesthesia. I couldn't believe it and went along to the theatre to verify the tragic news. The next day Pat's husband, Squadron Leader Boxall and Group Captain Irving arrived and took us to join the other wives and children for evacuation. I must thank Phyllis Briggs for burying my late husband'.

Scarf was buried the following day at Alor Star. The married women were evacuated first and thus the Nurses who remained at Alor Star found a coffin for him from the jail. Whilst driving to the burial, they came across a pair of Padres, who duly agreed to preside over the formalities.

His remains were later exhumed for an official re-burial in the Taiping War Cemetery under the auspices of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. His gravestone was additionally inscribed:

'HIS LOVE OF LIFE WAS ONLY EXCEEDED BY THE COURAGE ENCOMPASSING HIS DEATH'

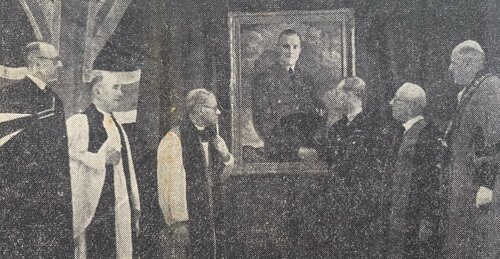

Such was the chaos which proceeded, that the actions of Scarf had to wait until 1946 to come to official notice. His parents donated a fund to produce the Scarf Trophy, to be awarded to the Far East Air Force Squadron considered best in weaponry. He is further commemorated at St Clement Danes Church, Aldwych, St Peters Church, Claypole, Lincolnshire, the National Memorial Arboretum and at the Bomber Command Memorial. Scarf Road, Canford is also named in his memory. A portrait was commissioned by the Old King's Club - to inspire future pupils at Wimbledon - painted by Edward Mossforth Neatby, being unveiled by Air Vice-Marshal Combe. It still hangs at the School today.

Sold together with the following archive of original material:

(i)

One of his rowing blades from school days, the wood painted red, shaft broken from the mid-point.

(ii)

Large-format school photograph, King's College School Wimbledon, June 1925, rather damaged.

(iii)

A number of family photographs and newspaper clippings related to his school and service life, besides three cassette tapes from radio programmes which feature his sister, notably the Radio Lincolnshire Report of John Scarf, by Kitty Ken.

(iv)

A number of framed images of the recipient.

(v)

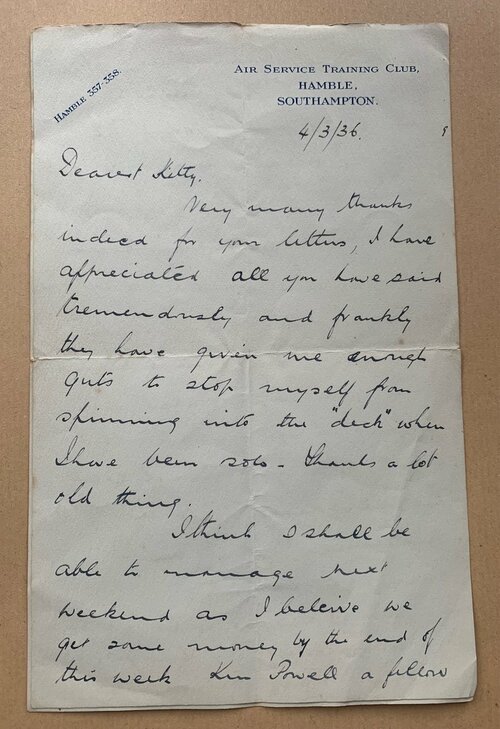

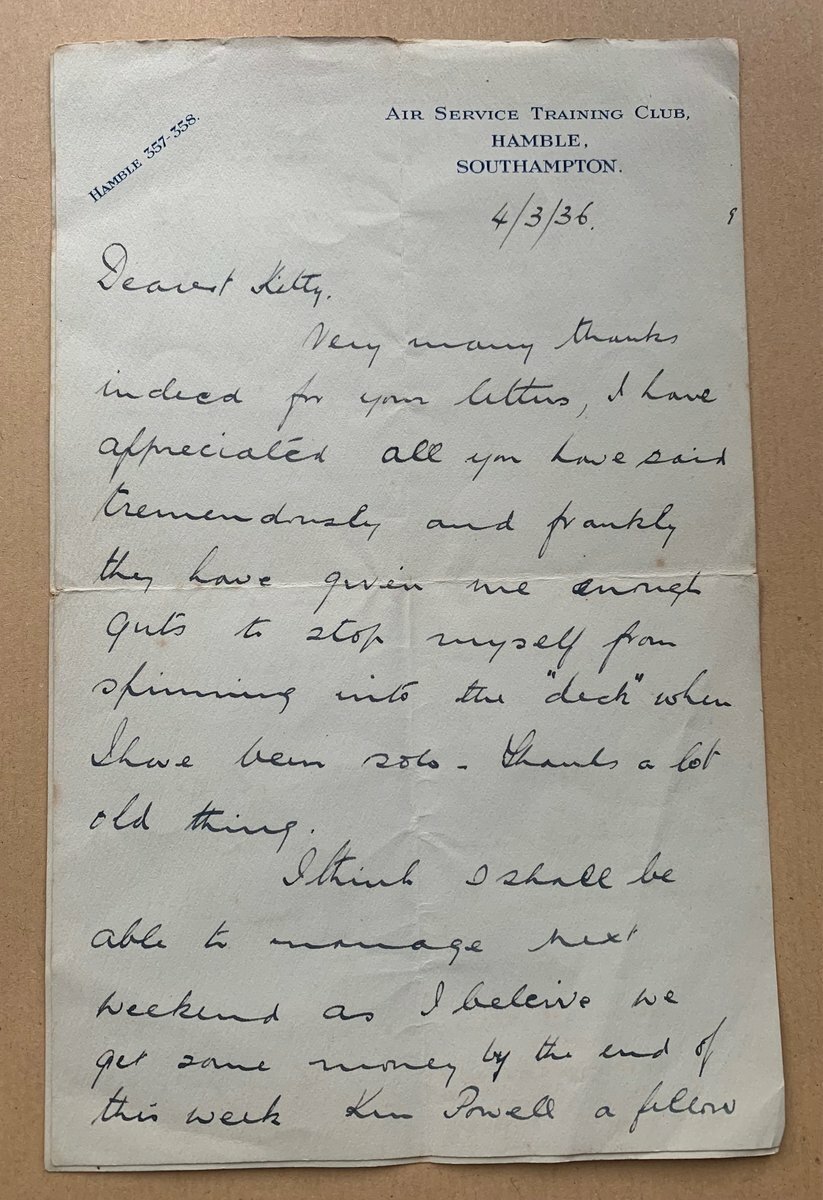

His letter, 4pp, written to his sister Kitty, on 4 March 1936 from the Air Service Training Club, with the moving opening lines:

'...I have appreciated all you have said tremendously and frankly they have given me enough guts to stop myself from spinning into the "deck" when I have been solo - thanks a lot old thing.

(vi)

The family copy of Angel Visits - from Biplane to Jet, with personal inscription:

'Best wishes from the author and with many memories of dear old Pongo and Hutch.', besides Devotion to a Calling - Far East flying and survival with 62 Squadron RAF and For Valour - The Air V.C.s, of which Chaz Bower closes his chapter on Scarf with the fitting words:

'How many other deeds of individual valour and intense devotion to duty during the dark days of 1941-42 in Malaysia remain unheralded is now impossible to compute or record. Perhaps 'John' Scarf's superlative gallantry and courage may stand not only as a worthy individual example, but as a form of memorial to those unknown men and women of the 'Forgotten War'.'

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£550,000

Starting price

£340000

Sale 22001 Notices

The typical engraving on the reverse of a Victoria Cross details the name, rank and unit of the recipient engraved on the reverse of the suspension bar and the date of action/period of action to the reverse of the Cross. This has been the practice since the inception of the award and includes the Royal Air Force awards for the Great War. However, there is an anomaly in respect of awards to the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. Research undertaken by Mr David Callaghan, former Senior Director of Hancocks, sole suppliers of the Victoria Cross, has revealed that, with one exception only, all awards of the Victoria Cross to the Royal Air Force for the Second World War show a date that is not the date of the action. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that the date engraved on these awards is the date on which King George VI approved the recommendation laid before him - thus the date from which the recipient was considered a holder of the Victoria Cross - rather than the date of their action which earned it. The last two examples which exhibit this fact were both sold in these Rooms. The posthumous V.C. group awarded to Wing Commander Hugh Malcolm was sold in April 2010. His Cross was engraved with the date 19 April 1943, whilst the award was published in the London Gazette of 23 April 1943. The period which earned his V.C. was 17 November-4 December 1942. The V.C. group awarded to Flight Lieutenant Bill Reid was sold in November 2009. His Cross was engraved with the date 7 December 1943, whilst the award was published in the London Gazette of 14 December 1943. The action which earned his V.C. was on 3 November 1943.