Auction: 21003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 143

'Heard on getting up that my dear good Annie Macdonald has passed away early this morning. I am most deeply grieved and cannot in the least realise that I have lost not only an excellent and faithful maid but a real friend

H.M. Queen Victoria in her Journal, 4 July 1897.

The important Victorian Faithful Service Medal awarded to Mrs A. MacDonald, Chief Wardrobe Maid, who stood on a par with the legendary John Brown in the life of Queen Victoria

MacDonald had broken the heart-breaking news of the death of Prince Albert to the grief-stricken Queen and put her to bed that fateful night; she was considered one of the closest friends to The Queen in her 41 years of devout service

Upon her untimely death during the Diamond Jubilee year - and having been forced to remain at Balmoral rather than join her mistress in Windsor - Queen Victoria halted celebrations for a Memorial Service, which took place simultaneously in Windsor, so that The Queen could pay her own respects; she also paid for a the raising of an impressive Memorial at Crathie Kirk

Upon the eventual passing of Queen Victoria, her final wish was granted, that she be buried with tokens of Annie MacDonald and John Brown in her left hand

Victoria Faithful Service Medal, reverse officially engraved ‘To Mrs Annie Macdonald Wardrobe Woman to Her Majesty For Faithful Services to the Queen during 35 Years 1892’, edge embossed as usual ‘Presented by Queen Victoria 1872, on its original tartan riband, in its Wyon, London case, nearly extremely fine and very rare

143 Victoria Faithful Service Medals issued, of which just 3 went to women, these being Emilie Dittweiler (No. 96), Annie MacDonald (No. 97) and Elizabeth Stewart (No. 135).

Anne Mitchell, who became Anne McDonald on her marriage, was born on 3 January 1832 and baptised a week later. She was a daughter of William Mitchell, a blacksmith of Cairnchuine, or Carn-na-Cuimhe, in the parish of Crathie and Braemar, and his wife, Margaret Gordon. Raised in the shadow of the old castle of Balmoral, the lease on which was acquired by the Prince Consort in 1848, Anne would have witnessed the redevelopment and rebuilding of the castle during 1849-56, of which the present Royal residence is the result. The acquisition by the Prince Consort of the Balmoral and Birkhall estates in 1852 signalled the Royal Family's intention of basing its Scottish country retreat upon Deeside and the recruitment of local people as servants began. Anne Mitchell was one of those servants, entering the service of the Royal Family in 1854, initially as a general cleaner or 'necessary woman' in the household of the Prince Consort.

By 1861, Anne had been advanced to the position of housemaid in the Prince Consort's household; it was in that capacity that she was present in an ante-room at Windsor Castle when the Prince Consort died, on 14 December 1861. Her account of Queen Victoria's distress at the death of Prince Albert has been quoted by many biographers of the Queen and the Prince Consort:

'It was an awful time, an awful time. I shall never forget it. After the Prince was dead, the Queen ran through the ante-room where I was waiting. She seemed wild. She went straight up to the nursery and took Baby Beatrice out of bed but did not wake her. That's so like the Queen. Orders were given at once for the removal of the Court to Osborne. All the servants were sent off in haste. It was thought necessary to get the Queen away as soon as possible. It seemed as though her grief would kill her. She did not cry - and they said that when she once got into the Prince's room, no-one seemed able to persuade her leave it. When the Queen did cry, she cried for days. It was heart-breaking to hear her.'

In 1862, the retirement of Marianne Skerrett - who had been a long-served principal dresser to the Queen - led to promotions and appointments within the ranks of the Queen's most intimate servants - her dressers and her wardrobe maids. At some point in the mid-1860s (the secondary sources, including the published recollections of Queen Victoria, disagree about the actual date) Anne was appointed one of the Queen's wardrobe maids, a position that she held until the end of her life. Several sources repeat the story that Anne was one of the women servants who eventually put the bereft and distraught Queen to bed after the Prince Consort's death, a sobering insight without doubt. Therefore, her intimacy with the Queen predated her appointment as one of her Majesty's wardrobe maids and possibly dated from the night of the Prince Consort's death.

In the summer of 1863, Anne, by then known as 'Annie', married a Royal footman, John Alexander McDonald, who was some four years her senior and a native of Newtonmore on Speyside. The marriage took place at Windsor and it was there, a year later, that the couple's daughter, baptised Victoria Alberta, was born. John McDonald died of tuberculosis in 1865 and Annie remained, like her Royal mistress, a widow for the remainder of her life.

During the many decades of the Queen's widowhood, Annie McDonald - the spelling of whose surname varies in both primary and secondary reference sources - became increasingly invaluable to Her Majesty. The Queen's evident preference for her plain-spoken Scottish servants is widely recorded and, from the 1860s, references to Annie in her Majesty's journals gradually increased. A footnote of 1866 in her Leaves from the Journal of our Life in the Highlands (published in 1868) records Queen Victoria referring to Annie as, 'an excellent person' and her regard for her wardrobe maid remained undiminished. The Queen's dressers and wardrobe maids accompanied her as the Court moved between the Royal residences and on the Queen's numerous travels abroad: the two maps of parts of France in this collection are evidence of this. The second volume of the Queen's Leaves …, (published in 1884) notes Annie McDonald being present on Royal visits to a variety of locations in Scotland almost annually between 1866-78. On one notable occasion, in September 1872 while the Queen was en route to Dunrobin Castle to stay with the Duke of Sutherland, Annie became locked in a room in a compartment on the Royal train, as the Queen recorded:

Here [at Keith] we were delayed by one of the doors, from the bedroom into the little dressing-room, refusing to open. Annie had gone through shortly before we got to Keith and when she wanted to go back the door would not open and nothing could make it open. [John] Brown tried with all his might, and with knives, but in vain and we had to take in the two railway men with us, hammering and knocking away as we went on, till at last they forced it open.'

Annie McDonald was much more than a wardrobe maid to the Queen. Such personal servants were the intimates of the monarch - far more so than the Ladies in Waiting - and, of necessity, knew how to arrange matters for the Queen almost before she knew that she wished them to be so arranged. Numerous biographers of Queen Victoria have recorded that she was a demanding mistress and that the lives of the dressers and, particularly, the wardrobe maids required a degree of commitment that would now be called '24:7'. Annie frequently slept on a sofa adjacent the Queen's bedchamber in order to answer her Sovereign's bell at any hour of the night: as the Queen aged, so those calls increased in frequency.

Space does not permit the detailing here of the extensive and continuous duties required of the Queen's wardrobe maids: this can be found in Kate Hubbard's Serving Victoria: Life in the Royal Household (London, 2012), where it is recorded that the duties were such that the health of wardrobe maids often collapsed under the strain. That Annie McDonald admirably fulfilled those duties, and more, through at least thirty-one years of personal service to Queen Victoria is exemplified not only by the award by the Queen of her Faithful Service Medal in 1892 but also by the letters and journal-entries of the Queen herself, in the final years of their relationship, as follows.

To H.R.H. The Princess Royal, Crown Princess of Prussia, 1st January 1888 [referring to Christmas Presents sent to Berlin],

'I am so pleased that my gifts gave you satisfaction and that you admired the [1887 Golden] Jubilee album. To Annie McDonald, superintended by me, the merit of the arrangement is due.'

Queen Victoria's Journal, 15th June 1897,

'Out with Lenchen [HRH The Princess Helena, Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein] and went to Clachanturn [from Balmoral] to see good Annie Macdonald. She was a good deal upset at the thought of not being able to return with me to Windsor. She is, I fear, very ill and very weak but one must still hope that she may regain her strength and possibly, though I scarcely think so, come to Windsor to direct things and show where they are. The trouble about arranging things for the [Diamond] Jubilee still continues.'

Queen Victoria's Journal, 4th July 1897,

'Heard on getting up that my dear good Annie Macdonald has passed away early this morning. I am most deeply grieved and cannot in the least realise that I have lost not only an excellent and faithful maid but a real friend who was absolutely devoted to me. She had been forty-one years in my service [actually 43], thirty-one of which as wardrobe maid and was quite invaluable.'

A rare advertisement of the Queen's personal grief at the death of a servant was published in The Court Circular of The Times on 5th July 1897:

'The Queen has once more had the pain of losing a most valued servant in Mrs McDonald, who had been for 40 years in the Queen's service, 31 of which as Wardrobe Woman. She expired yesterday at Clachanton [sic] after a short illness. Mrs McDonald was a most devoted and excellent servant and true friend of the Queen's, who deeply deplores her loss.

Mrs McDonald was in her 68th [actually 66th] year, a native of Crathie, and universally beloved.'

And, in same location, on 9th July 1897, reporting events of the previous day:

'By special command of the Queen a memorial service for the late Mrs Macdonald, wardrobe dresser to her Majesty, was held at 1 o'clock yesterday afternoon (simultaneously with the funeral service at Crathie) at the Congregational Church, Windsor, which place of worship was attended by Mrs Macdonald when resident at Windsor. Her Majesty was represented by Sir James Reid, Colonel Browne (Groom in Waiting) and two Ladies in Waiting. The heads of department in the Castle were also present.'

It is evident that the Queen mourned Annie McDonald for the remaining years of her life. Towards the end of her Diamond Jubilee year, 1897, she compiled 'Instructions for my Dressers to be opened directly after my death and to be always taken about and kept by the one who may be travelling with me'. Among the list of items to be placed with the Queen in her coffin was, 'some souvenir of my faithful wardrobe maid Annie MacDonald'. Once the Queen had been placed in her coffin - by the new King, the Kaiser, the Duke of Connaught and his son, Prince Arthur of Connaught - Sir James Reid, the Queen's physician-in-ordinary, placed a photograph of John Brown and a lock of his hair inside a small silk case worked by Annie McDonald in the Queen's left hand.

Annie McDonald was, with John Brown, about whom so much has been written - and speculated, the only commoner to receive specific mention in the Queen's Last Will and Testament. When drafting it in 1898, the Queen wrote, inter alia:

'I die in peace with all … I hope to meet those who have so faithfully and devotedly served me, especially good John Brown and good Annie Macdonald, who I trusted would help to lay my remains in my coffin.'

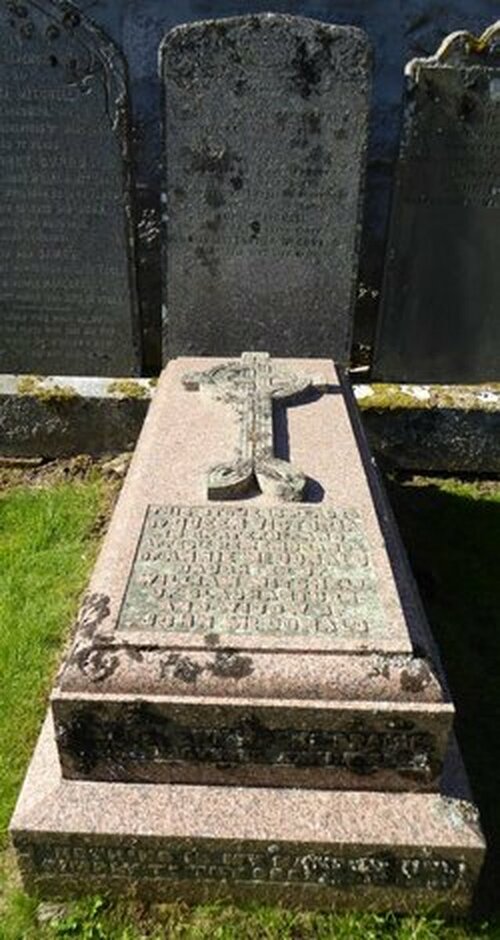

Annie was buried in the graveyard at Crathie parish kirk - the same resting place as John Brown - beneath a massive and impressive tomb of pink Aberdeenshire granite contributed by the Queen and deeply cut with the inscription:

'THIS STONE IS PLACED BY QUEEN VICTORIA IN GRATEFUL & AFFECTIONATE REMEMBRANCE OF ANNIE McDONALD, DAU. OF WILLIAM MITCHELL OF CLACHANTURN & WIDOW OF JOHN McDONALD.

SHE WAS BORN AT CARN-NA-CUIMHE 3 JAN. 1832, D. AT CLACHANTURN 4 JUL.1897, BELOVED AND MOURNED BY ALL WHO KNEW HER.

SHE WAS IN THE QUEEN'S SERVICE FOR 41 YEARS & DURING 31 YEARS WAS WARDROBE MAID AND THE FAITHFUL SERVANT AND DEVOTED FRIEND TO THE QUEEN BY WHOM HER LOSS IS DEEPLY DEPLORED.'

It seems likely that Annie did not expect to die at the age of 65: it must be inferred that her last illness and death followed quickly upon one another, since she died intestate. The net value of her estate amounted to a little in excess of £1,300 (more than £1million today).

Annie's daughter, Victoria Alberta - apart from a period at the exclusive St Margaret's School for Girls in Aberdeen in the 1870s and '80s - appears to have lived with her mother's family at Clachanturn until her mother's death. At Crathie on 4th November 1897 she married Alfred Blaker, a Leeds-born Revenue officer based at that time at Cardigan in west Wales: the Queen was one of the witnesses to the marriage.

Thus Annie McDonald: faithful, trusted and devoted personal servant of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. Her few remaining treasures - which would have meant so much to her during her life - remain with us today as symbols of the life and service of a nineteenth century Royal servant of the highest order whose care and support for Queen Victoria remained as reliable and constant factors in the long life of that monarch.

A painting of McDonald, painted by The Queen, is in the Royal Collection Trust (although it has not yet been added to the searchable database) and is understood to hang at Osborne.

Sold together with the following personal items:

(i)

A charming gold (unmarked) brooch, bearing the letters 'VR' besides the Crown, enhanced with the flowers of the Union, surely a personal presentation item from the hand of Queen Victoria to the faithful Annie.

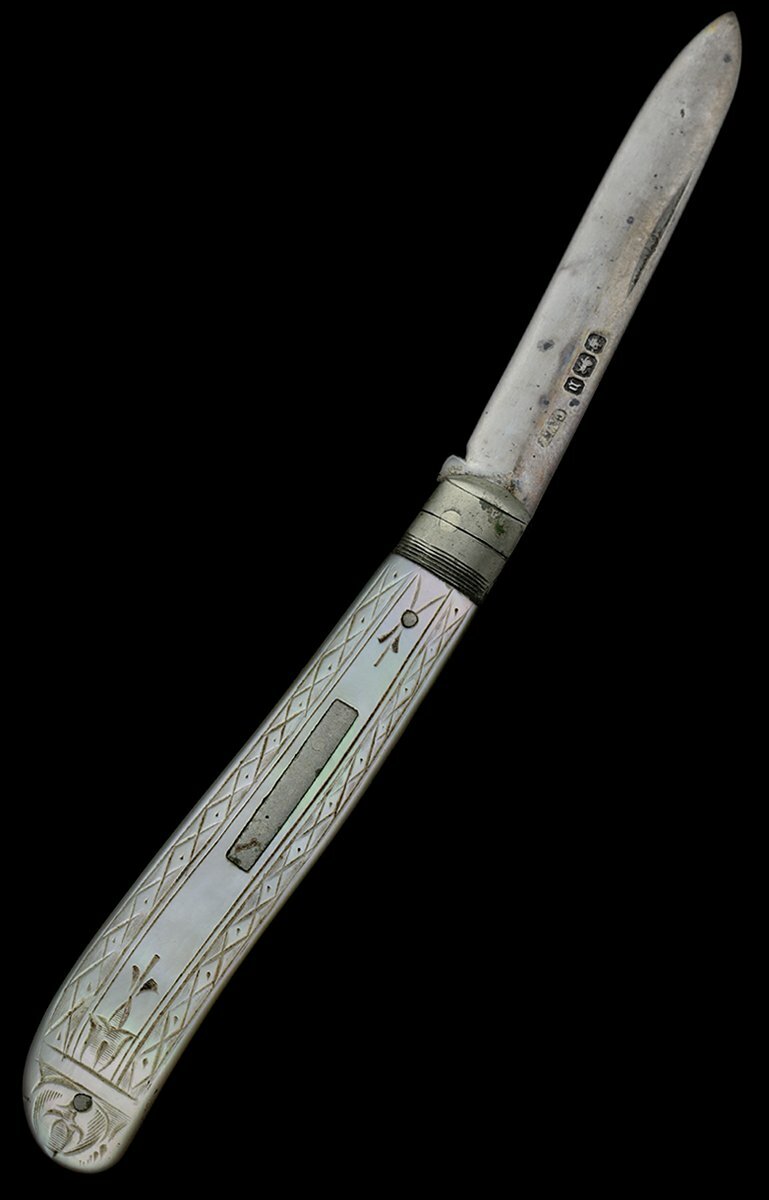

(ii)

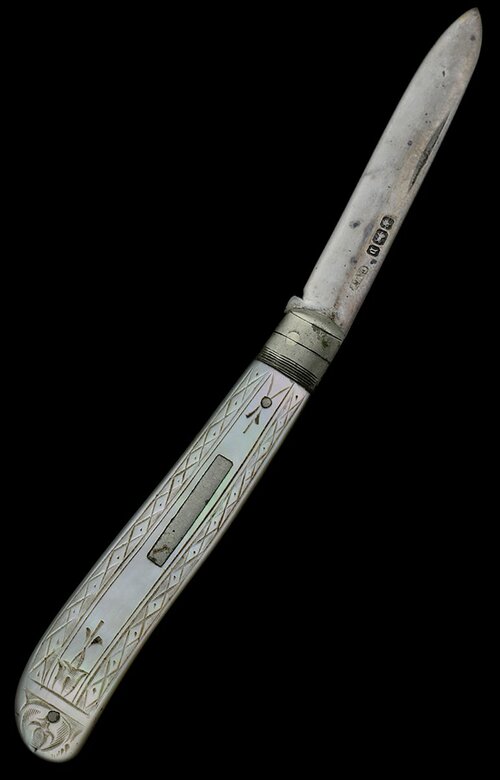

Her silver and mother of pearl fruit knife, the blade hallmarked, surely sometime used in the preparation of fruit for The Queen.

(iii)

Four of her fobs, including a kettle with the initial 'M' (for MacDonald) engraved to the stone set in the base.

(iv)

A black leather folder, embossed with the Royal Coat of Arms, contained within it a map of Toulon and a superb map of the Railway from Paris to Amiens, ornately gold embossed with the Napoleon Family Coat of Arms and 'N', presumably from a Royal Visit to France by rail, with small photographs with details affixed, this in sections but in good condition.

(v)

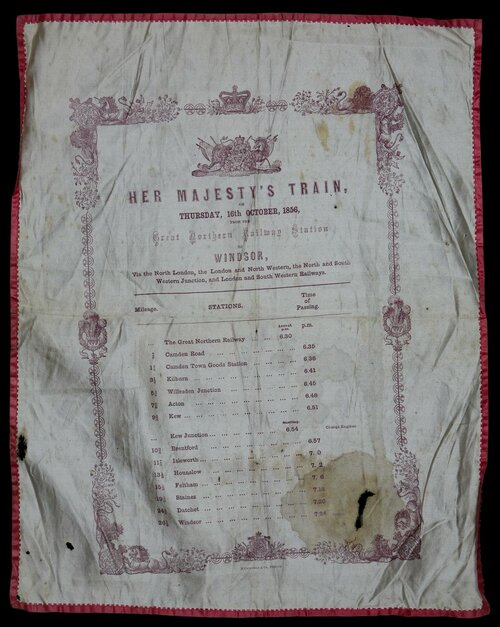

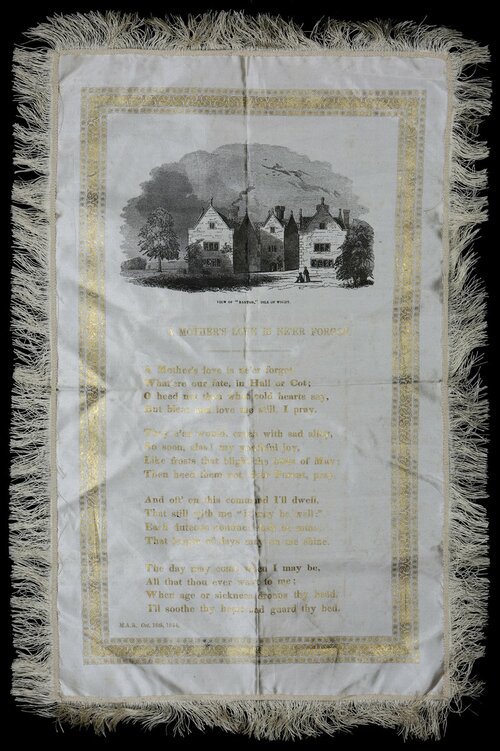

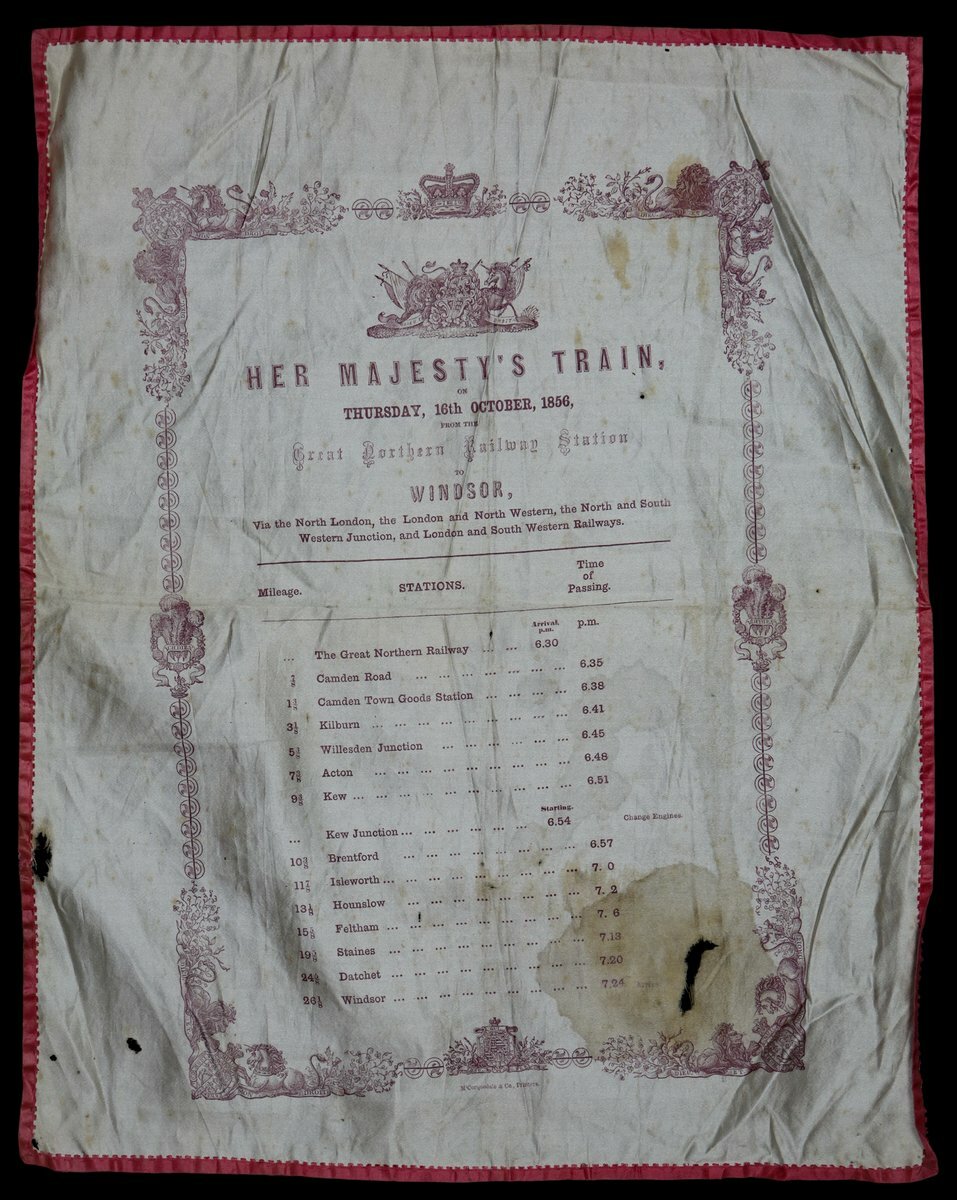

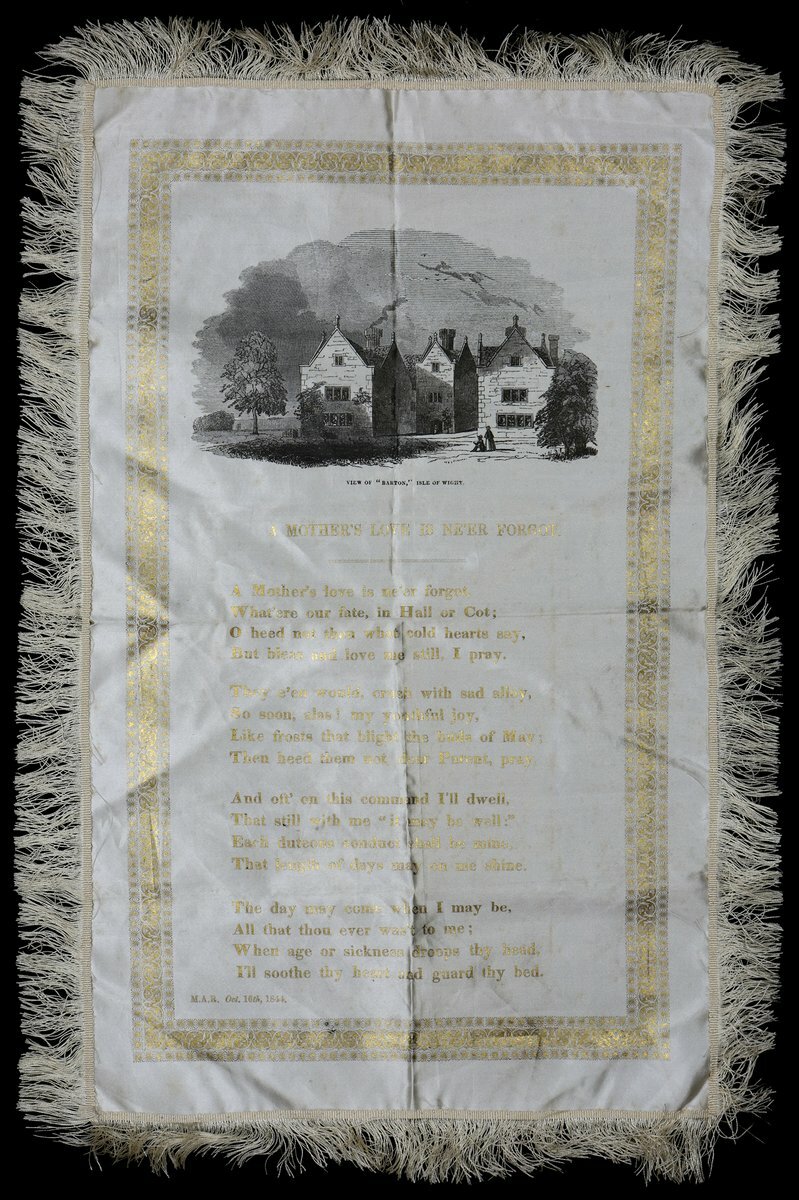

Two silk programmes, one for the Royal Train journey from Great Northern Railway Station to Windsor, 16 October 1856 and the other with the poem 'A Mother's Love is Never Forgot.'

(vi)

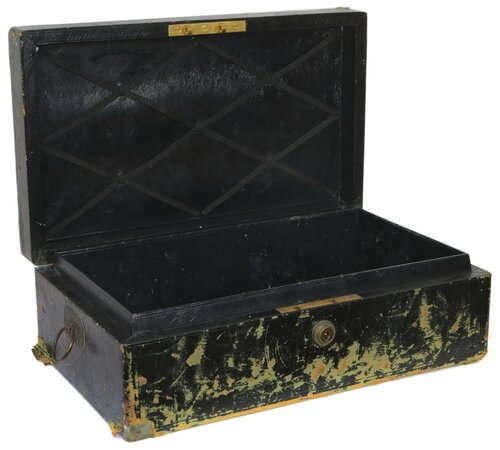

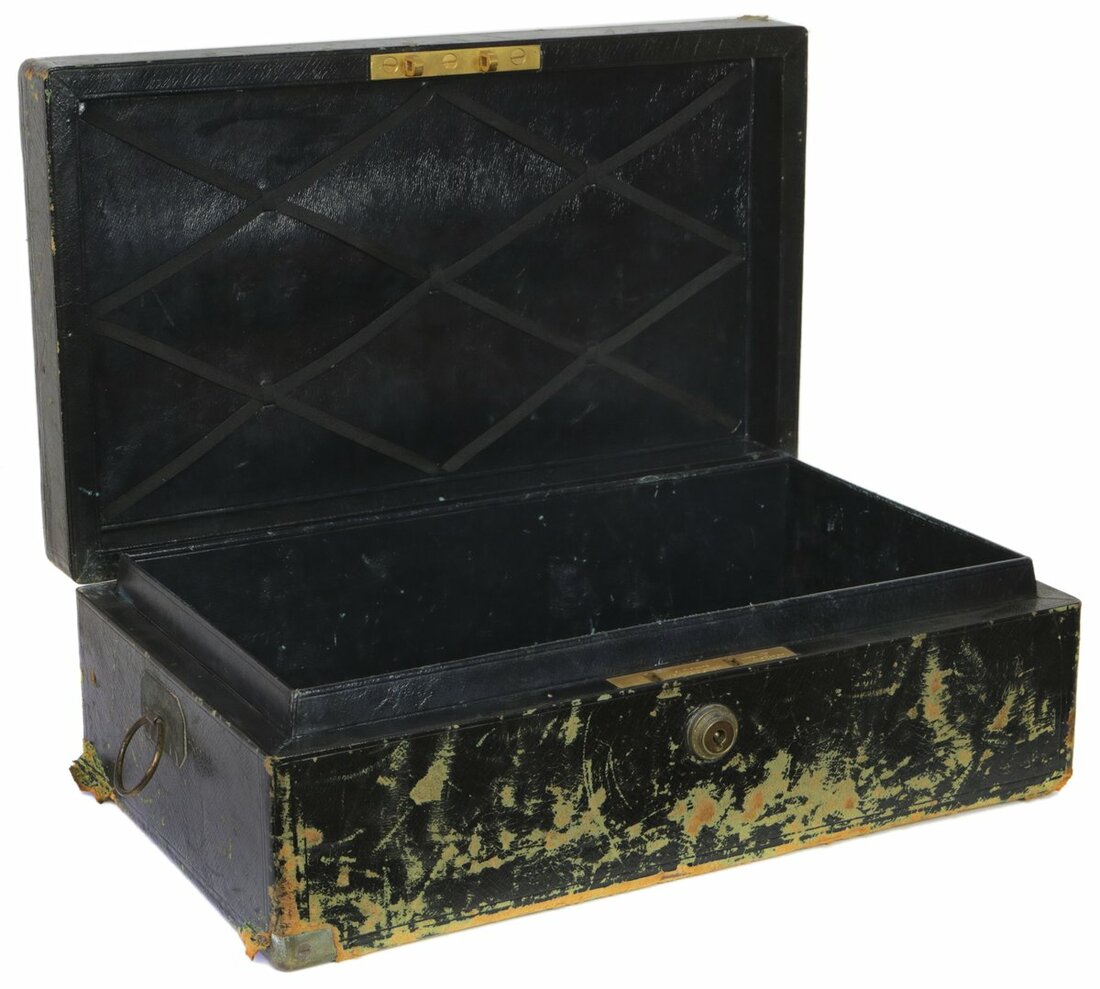

Her leather writing box, by P. West, Manufacturer to Her Majesty & The Royal Family, 1 St. James's St, with lock by J. T. Needs, leather worn from use, all housed within a large wooden box.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£4,200

Starting price

£4500