Auction: 20001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals - conducted behind closed doors

Lot: 1023

'While jumping from his plane, his parachute caught fire and he died from his burns at Rosendael Casualty Clearing Station on the 3rd of June 1940. He was most cheerful and not in great pain. He passed into a coma a few hours before his death. He was a grand chap. You will judge how much to tell his relatives.'

Major P. H. Newman, R.A.M.C., writing about the fate of Flying Officer H. P. Dixon in a letter sent from Oflag IX in March 1941.

A well-documented and poignant Hurricane ace's 'Fall of France' campaign group of three awarded to Flying Officer H. P. Dixon, Auxiliary Air Force

A pre-war Cambridge graduate who additionally served in the University Air Squadron, Dixon was commissioned in No. 607 Squadron of the Auxiliary Air Force in 1936

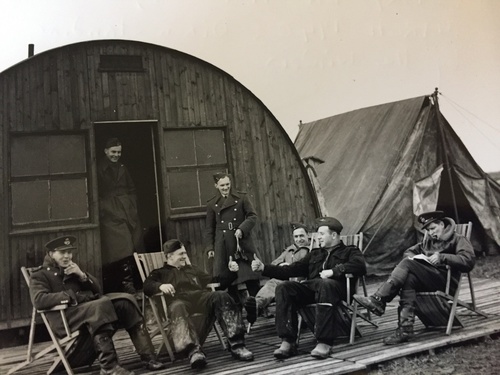

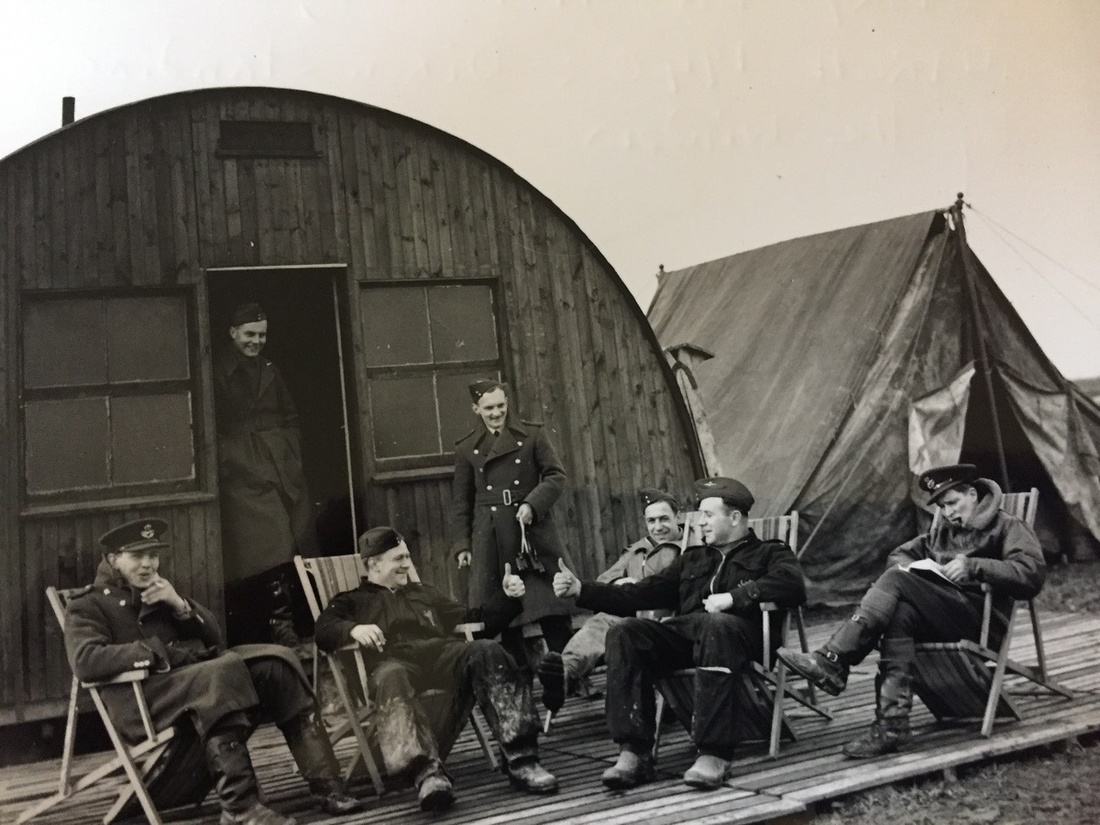

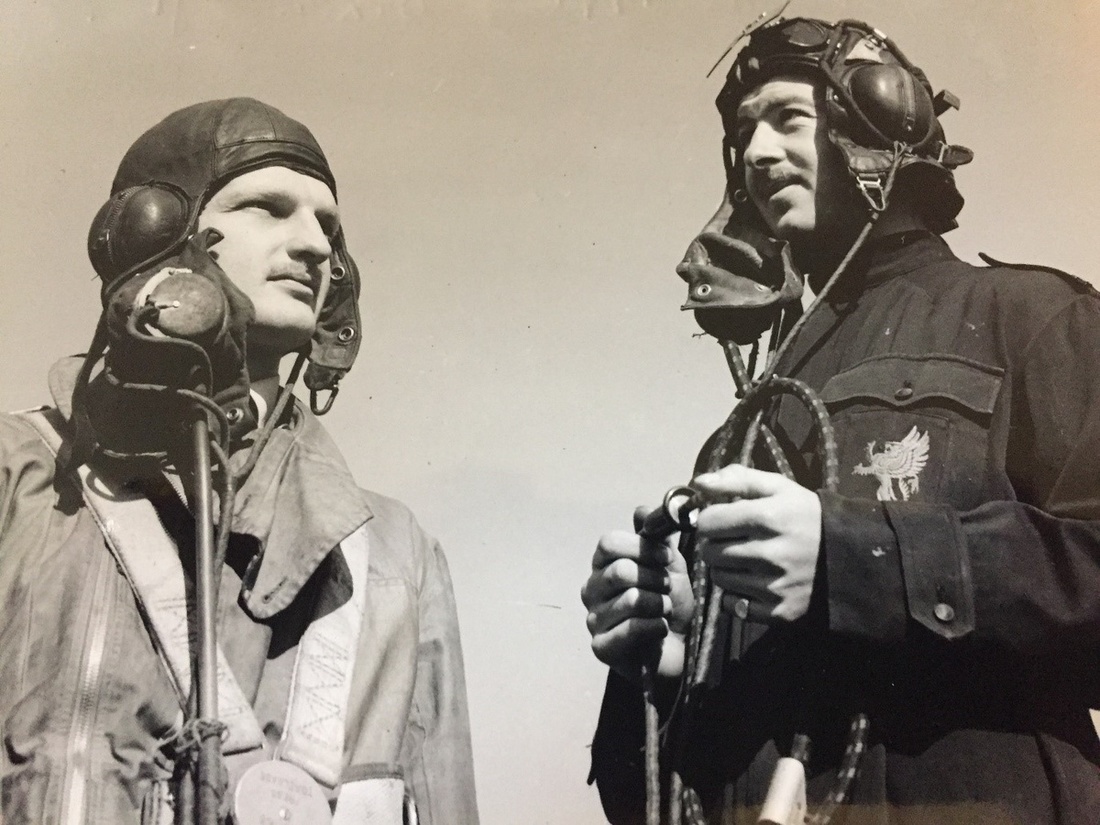

Called-up in August 1939 - and having seen action over the North Sea in 607's antiquated Gladiators - he converted to Hurricanes after joining the Advanced Air Striking Force in France. The subject of a royal visit and a press call - from which emerged some memorable Daily Sketch images of Dixon - 607 shared in the costly air battles marking the advent of the Blitzkrieg

His own part in those operations in May 1940 was exemplary, five enemy aircraft falling to his guns in as many days but, on being re-assigned to No. 145 Squadron, he was shot down off Dunkirk on 1 June 1940. His brother, John, witnessed the incident, standing on the Mole, but had no idea of the unfortunate airman's identity

Recently released Air Ministry casualty records poignantly document the protracted and painful journey endured by his family in securing the truth about his fate: it finally emerged that Dixon - suffering from extensive burns - had been plucked from the sea and died in a coma at a Casualty Clearing Station two days later

1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star; War Medal 1939-45, with related Air Ministry condolence slip in the name of 'Flying Officer H. P. Dixon', in original forwarding box addressed to 'J. R. Dixon, Esq., Quarryston, Heighington, Darlington', extremely fine (3)

Henry Peter Dixon - known by family and friends as Peter - was born at Darlington, County Durham on 12 February 1915, the son of John Reginald and Elsie Margaret Dixon. Educated at Sandrock Hall in Hastings, Sussex and Marlborough College, Wiltshire, he then attended Sidney Sussex College Cambridge and graduated in June 1936; a member of the University Air Squadron, he gained a civilian aviation pilot's certificate in the same year.

Having then joined his father's engineering company in Darlington, he maintained his flying skills as a newly commissioned Pilot Officer in No. 607 Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force. Subsequently absent from 'weekend flying' on account of his new post with an engineering company in Calcutta, India, Dixon was recalled to arms in August 1939.

One of three pilots to fly 607's very first operational sortie - taking to the skies in 'A' Flight's Gladiators under Flying Officer Francis Blackadder in a recce on 3 September 1939 - he also participated in a combat over the Forth of Firth in October.

Advanced Air Striking Force - 'Phoney War'

Ordered to France in November 1939, Dixon and his fellow pilots were inspected by H.M. the King at Merville in the following month, from whence they re-mustered at Virty-en-Artois.

The ensuing 'Phoney War' period may have tested the patience of some but for the aircrew of 607 Squadron, it provided a welcome break. Dixon, as the unit's Mess Secretary, rarely failed to impress his comrades, securing all manner of precious supplies and laying-on excellent outings, thus a visit to the Lido nightclub in Paris to see Josephine Baker - and Maurice Chevalier - perform. On another outing to Lille's finest fish restaurant, Dixon collided with a Major-General on exiting the establishment and, to the amusement of his comrades, beat a rare retreat.

Meanwhile, 607 dutifully undertook a regular agenda of patrols in their antiquated Gladiators until, in March-April 1940, they were re-equipped with Hurricanes; this the period in which journalists of the Daily Sketch made a special journey to France to tell the story of the Advanced Air Striking Force's Auxiliary Air Force units.

Advanced Air Striking Force - Real War

At dawn on 10 May 1940, the Blitzkrieg commenced with infuriating German efficiency, 607 Squadron being among the first to encounter the ferocity of the enemy's air offensive, its airfield being strafed by Me. 109s.

Dixon was in action over Douai by 0530 hours and, during his third and fourth patrols of the day, he gained his first 'kill' and faced accurate return fire. His combat reports state:

'I was flying Red 3 on patrol when four He. 111s were sighted being attacked by three Hurricanes. One dropped back with starboard engine revving slowly. I attacked, which stopped its port engine. The aircraft then released its bomb loads in fields and was seen gliding down for the ground with both motors stopped. Resumed patrol.'

And:

'I sighted A.A. fire and headed towards it, and saw enemy bombers. We attacked individually owing to the scattered enemy formation. We attacked five aircraft, my own aircraft was hit in the oil tank …'

On 11 May, on his second sortie of the day, Dixon was back in action with his old friend Francis Blackadder. The latter later recalled:

'I was leading a flight near Brussels. After a while a single aircraft was observed flying south-east some way off. We gave chase and found it to be a Heinkel, and after quite a battle shot him down in flames - the bomber fell on a house that had been evacuated. We circled around and I was just setting off back for the patrol line when Peter Dixon, who had been flying on my right as Red 2, called me up and talked of some more bandits. I did not receive the message clearly, but on looking round saw one machine setting off further east, so I followed. Soon I saw what he had seen, namely a score of black specs. We joined up and climbed up after them, and before we got near they had been joined by another large formation of E/A. Luckily two Heinkels dropped slightly behind, so Peter and I each took one.

That was the last I saw of him. I had seen a formation of single seaters - 109s - approaching and, imagining they were ours and having finished my ammunition, I pulled up towards them, only to see their rude black crosses, so I hotly fled and eventually force-landed in a field.'

As it transpired, Dixon had kept on the tail of his adversary, his gunfire killing the rear gunner, but as the enemy aircraft trailed smoke from its engines, he was compelled to break off the action of account of shortage of fuel and ammunition. The options looked bleak before he sighted a shell cratered airfield near Tirlemont and managed to land in between the craters. It was abandoned.

Hailing a passing column of Belgian troops - and after a battle to establish his true credentials - he set off in search of fuel with their assistance. But by the time they returned to the abandoned aerodrome, the Luftwaffe had transformed his Hurricane into a smoking heap. His only option was to join a column of refugees but, by good fortune, he managed to hitch a lift with a Belgian Army officer and thence, with some Belgian airmen. At Louvain, he met a Wing Commander who got him to the Belgian Army H.Q. in Brussels.

Put up in a grand Chateaux, he met Sir Roger Keyes and the British Ambassador, Sir Lancelot Oliphant, the latter arranging for his onward journey back to 607 Squadron at Vitry. Meanwhile, he had been posted 'missing'.

Quickly back on operations, Dixon flew a flurry of sorties between the 12th and 16th May and was credited with a brace of He. 111s from 9/KG51 on the 15th. The following day, in a dogfight with five Do. 17s - he claimed one as a probable - his Hurricane was badly damaged by return fire, a bullet just missing his foot. He also ran out of oxygen at 17,000 feet. His subsequent landing at Vitry was undertaken at great speed, owing to his Hurricane's damaged wing flaps. A fellow pilot later recalled how the exasperated Dixon said he would have called up an ambulance and fire engine to meet him in normal times.

Mounting losses were indeed taking their toll - 607 had lost four Hurricanes and three pilots in recent days. Finally, on the 18 May, orders were received to proceed to Boulogne, where some aircrew were embarked in the good ship Biarritz. But Dixon and his friend Peter Parrott managed to hitch a lift in an ATA Ensign aircraft to Hendon. They were granted 10 days' leave.

Dunkirk - 'Missing'

Their period of leave was interrupted the following weekend by the arrival of telegrams ordering them forthwith to No. 145 Squadron at Tangmere. So just four days after departing France they were back on operations, Dixon claiming a 109 and a Ju. 87 unconfirmed over St. Omer on the 22 May. He was to re-visit St. Omer on the following two days, prior to being granted 48 hours' leave.

By the time he returned to his squadron, Operation "Dynamo" was in full swing. Hence trips to the Dunkirk sector in the closing days of May and, likewise, on the first day of June. On that date, and having already completed one sortie, Dixon acted as 'weaver' to a squadron formation over Dunkirk around midday. They sighted and attacked a large force of Me. 110s and 109s, a combat witnessed by our troops gathered on the Mole at Dunkirk, who cheered on the R.A.F.

Major John Dixon - Peter Dixon's brother - was among them and later recalled seeing one of our aircraft on fire, falling with the pilot underneath on a flaming parachute. The airman was quickly recovered from the sea by one of our small craft and delivered to a dressing station on the Mole. Beyond his immediate thoughts for the gallant airman, John Dixon thought nothing further of the incident. But on getting back home in the destroyer H.M.S. Icarus, he was informed by his parents of Peter's 'missing' status.

Dunkirk - found

As cited above, a long and painful period ensued for Peter's family, for conflicting evidence was received that he had been embarked on a ship, which was later sunk by enemy aircraft. His friend, Peter Parrott, later recalled:

'On the 1st June I had been given a day off to go to London to get a new uniform. On my return to Tangmere in the evening I was told Peter was 'missing'. A day or two later we heard he had 'belly-landed' on the beach at Dunkirk, badly wounded. Later still we heard that he was seen on a stretcher being loaded aboard a destroyer, then the final blow the destroyer was sunk.

In the short time we had known each other we became close friends and, had he survived, I am sure we would still be close. He was the most likeable person, with a good sense of humour, kind, generous, and truly a gentleman.'

With other potential witnesses since killed in action - or taken prisoner of war - the Air Ministry abandoned its lacklustre investigation. But already on file was a letter written by Major P. H. Newman, R.A.M.C., who had treated Peter at a Casualty Clearing Station, written from a distant Oflag in Germany; as quoted above.

The relevant Air Ministry casualty files, released in 2012, chart Peter's father's personal efforts to seek the truth. He managed to track down Flying Officer Michael Carswell, a fellow Tangmere pilot who was also shot down on 1 June 1940. Carswell was able to confirm that he had seen Peter being evacuated in an ambulance, suffering from severe burns, which facts entirely supported Major Newman's evidence. Finally, in the summer of 1942, a conclusive report was sent to Peter's parents.

And it was on the back of such evidence that his grave was located at Rosendael after the war, his remains being transferred to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's cemetery at Dunkirk in November 1948.

Sold with a quantity of original documentation and uniform, comprising:

(i)

The recipient's Civil Aviation pilot's licence, with portrait photograph, dated 30 June 1936.

(ii)

A fine quality studio portrait photograph of the recipient in uniform, taken on the occasion of him being commissioned as a Pilot Officer.

(iii)

A 607 Squadron 'B.E.F.' card, with silk riband.

(iv)

An Air Ministry letter, dated 13 May 1940, addressed to the recipient's father, confirming his son's safe return to his unit: 'Details as to how his aircraft was reported missing are not yet known, but it is understood that your son was uninjured, and no doubt he will write to you direct in the near future.'

(v)

An Air Ministry telegram, addressed to the recipient's father, reporting his son missing in operations on 1 June 1940, with Post Office envelope.

(vi)

The recipient's Mess Dress, comprising jacket, waist coat and trousers, each with ink inscription 'H. P. Dixon' to inner lining.

Together with a comprehensive file of copied research, including correspondence with the recipient's brother, Peter, following the original sale of these medals and archive at auction in March 1993, and with pilots who flew with him in 1940; and, as stated, a mass of deeply moving correspondence charting his family's battle to establish the exact fate of his fate.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£3,500

Starting price

£600