Auction: 19003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 398

A remarkable Great War A.F.C. group of four awarded to Major H. F. Champion, Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force, late Rifle Brigade and South African Infantry

Having commenced his war fighting across German Southwest Africa, Champion obtained a commission and was swiftly whisked off to the Western Front

With a passion for aviation, he found himself cutting his teeth as an Observer with No. 20 Squadron on a dangerous mission over the trenches in February 1916 - being shot down with his Pilot and accounted as the Squadron's first loss

Following a bumpy crash-landing he ended up 'behind the wire' and restless - immediately plotting his escape after some careful planning and the below-par tailoring of a French officers tunic

Having somehow avoided detection in frightful conditions including being chased through snow-laden forests by wolfhounds and taking shelter in a woodcutters lodge, Champion and his comrade made it across the Swiss frontier and into the arms of a trusty local whose wife provided much milk and bread for the frozen adventurers - he also concealed them from a German patrol which lay in wait for their British quarry

It was some fifty-two days after his initial capture that Champion completed his 'home run', writing himself into the record books as just the second such officer to complete the feat

Air Force Cross, G.V.R.; 1914-15 Star (Pte. H. F. Champion 7th Infantry); British War Medal 1914-20 (Major H. F. Champion. R.A.F.); bi-lingual Victory Medal 1914-19, with M.I.D. oak leaves (2. Lieut H. F. Champion. R.F.C.), mounted as worn, the third with officially re-impressed naming and loose upon claw, otherwise good very fine (4)

A.F.C. London Gazette 2 November 1918.

Hillary Francis Champion was born at Chislehurst, Kent on 27 March 1894. Educated at Eastbourne College, where he was a member of the Officer Training Corps, going out to South Africa in 1913 to Bloemfontein. Having joined the 1st Kimberley Regiment, he served in German Southwest Africa from 6 October 1914. Champion was subsequently demobilised from his unit and enlisted in the Rifle Brigade, being commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion and thence transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in November 1915.

Joining No. 20 Squadron on 17 January 1916, he was sent skyward in an FE2b on 29 February with 2nd Lieutenant A. Newbold on a mission over enemy lines. They found themselves shot up by a Fokker piloted by Vizefeldwebel Wass and heading to earth at great speed.

No explanation penned by the cataloguer could describe the incredible scenes quite as well as recalled Champion himself, thus they are quoted verbatim for your enjoyment and they make a terrific read:

'I do not know why exactly I should have been persuaded by the Editor of The Outspan to tell this story of escape, except it be that adventures of escape seem to have suddenly become prominent in films which have been exhibited in South Africa recently and he probably imagined, therefore, that a story of escape, particularly concerning a South African, might be of some interest to thousands of people throughout the Union, who have lately seen films such as "The 'W' Plan", "The Case of Sergeant Grischs", of "Escape", from the play of Galsworthy.

The story of my escape as a flying officer and prisoner of war is really the history of fifty-two days - from February 29th to April 21st - in the year 1916.

Still very vividly I can recall the events of that day when I was taken prisoner. On the previous night I remember orders came through that a reconnaissance party of one machine, and three others to act as escort, was to be sent out on the morrow to ascertain the exact position of four enemy aerodromes - the approximate positions being known. At an hour before dawn I tumbled out of the Armstrong Hut which acted as our headquarters - and which at that time was a very little different from an ice chest, for the winter of 1915-16 was surely the coldest and wettest period of the war. No stars were to be seen and the wind was bitterly cold. Visibility was very poor owing to clouds and rain but later on it became surprisingly good as we crossed the south of Ypres and flew along the Menin Road.

We spotted two of the aerodromes fairly easily, and then all in a moment it seemed there came the pip-pip-pip of a German machine-gun. I immediately got my gun into action, but suddenly another German 'plane opened fire below and then two more appeared on our right. I emptied then two more drums in the fighting that followed and things became pretty desperate - partially as my gun gave me a lot of trouble owing to ice forming after the rain. In the midst of everything my engine stopped and I saw that petrol was pouring from a large gash in the service tank. Looking at my aneroid and observing that we were now only 3,000ft up I at once began to dismantle my gun and throw it piece by piece overboard - an action which probably took less than a minute, but by this time we were probably not more than 1,000ft in the air. Looking for somewhere to land, I saw a large open field. I had visions of missing a roof by inches; then a bump and a bounce; and finally I was conscious and climbing dazedly out of the cockpit and walking straight into the arms of a German. Germans were running up from all sides and eventually a general rode up and observed, "You is two Officers Scotch? Hein." - for he had evidently mistaken the R.F.C. cap for that of a Highland regiment. Civilians also started to arrive and an order was given to make a circle round the machine. There was a great deal of shouting, and as the Belgian civilians came surging near us, an Officer drew his revolver and fired twice into the air. Quickly the Belgians withdrew, and in a very little time we were driven away into captivity.

I do not intend this article to attempt to describe the conditions under which we were help captive during those first few weeks. All that I will say is that we lived under very mixed sort of conditions - and let it go at that. I take up the main thread of this narrative when I come to describe to you the day on which we were transferred to a new camp called Vohrenbach in the Black Forest - a camp which certainly did have "possibilities", inasmuch as it was new and near the Swiss frontier. The new camp consisted of a school apparently just completed and stood on the outskirts of a small village very beautifully situated amid pine-covered hills and completely covered in about two feet of snow. When our party, consisting of Newbold, Binny and myself and sixteen Frenchmen, arrived, there were about eighty Frenchmen and four Russians already in occupation. War, Alexander, Goodman and Mackay arrived a few days after we did, and so we seven British and a dear old Roman Catholic Padre, serving with the French infantry, had a room to ourselves. We had an excellent mess. The Germans allowed us to use spirit stoves and we only had the midday meal at the Germans' expense, which was a tremendous change from conditions we had endured at the previous camp where our food - but, there, I said I would keep off that.

Most of the fellows had been prisoners some time and got parcels regularly, and for supper on my birthday I find that my diary gives the following menu:-

Kidney soup, poulet roti, vegetables, aparagus, trifle (our recipe), chocolates and liqueur brandy.

For pastimes we studied languages, read, played chess, bridge and hockey, and for a time there was a great rage for diabolo.

As you can imagine, our topics of conversation were very limited, but there were two subjects of which we never tired. For hours we would discuss how long it would take before Germany was exhausted - a possibility which seemed very remote at the time. But even this topic paled into insignificance beside the much more absorbing and tantalising topic of escape. Day after day, night after night, we thought over all the ways and means. On one occasion, I remember, we thought we had found a way out by an 18-inch drain - only to discover, however, that this was barred at the further end and in full view of the sentries. Disguise, of course, was always a difficulty. The doctor had a spare uniform and cap just inside the door of his room and several attempts were made to steal these. One of our fellows - Alexander - lost his cap, and at the German hospital he was given a civilian one. As soon as he arrived in the camp I cast envious eyes on it, and as he showed no intention to escape at the moment owing to wounds, he gave it to me. Then our orderly managed to get me a pair of corduroy pantaloons, for which I gave him five francs. I believe they were in issue to French Algerian troops. No matter, they would pass as civilian. And so the days went on until one Friday, the 11th of April, when the French advised that Vohrenbach was to become a reprisal camp against the French after their ill-treatment of some German prisoners of war in the Pyrenees. As the reprisals were to be directed solely against the French, the English and Russians were to be sent to Heidelberg. This at once set me to furiously think, for here was certainly an opportunity, even though it might be difficult to make any fixed plan. On the following Saturday we had plenty of time to ourselves, for the Staff were busy all day removing the Frenchmen's beds, and during this time all available maps of the Swiss border were copied by Newbold, Mackay, Ward and myself. Newbold and Mackay were full of ideas; they even went so far as to make arrangements to carry their uniforms so that they might have something to wear in Paris.

I worked on my own, the only ones in my confidence being Edouin and a Chasseur captain, to whose dark blue coat I had taken a fancy. Edouin insisted upon my taking a dark grey cardigan which he treasured (a blessing, as future events proved), while Alexander gave me his cap, a beautiful brown tweed affair called "The Margate". The only trouble about my outfit was the coat. The colour wasn't bad, but the cut was too military, so I got to work with a pair of scissors, needle and thick black cotton. After an age I managed to do away with the military cut, but I cannot say that the coat, as a coat, had been improved, for my tailoring was certainly not facilitated by the fact I had to work under my bed out of sight of the Germans. On Monday night Ward and I discussed ways and means, and found that our ideas were not at variance, and decided to try our luck together. We were simply to take any opportunity that offered. One plan was to get into the middle of a column of prisoners, and when we were turning a corner, close to a wall, to slip off our coats and lounge against the wall as spectators, the idea being that the guards in front would have their backs to us and those behind would not yet be round the corner. Our baggage consisted of two tins of bully, bread, a bottle of milk tablets, chocolate, and our precious but inferior copy of the map of the Swiss frontier - these to be carried in an old linen bag. We had no compass, but we lived in hopes that it would stop snowing, and we could then take direction by the sun. On the Tuesday morning we dressed in our disguises, and tucked our trousers into our stockings, then donned our leather great-coats, thus hiding our sins. On the way down to the station, Newbold's bright blue trousers began to slip down his leg and peep out below his coat; and Ward and I shouted and abused him until he managed to adjust the fault.

A long coach was awaiting us at the station, and, in order that you may understand what follows more clearly, it may be better that I should describe this coach in detail. The best description I can give to it, I think, is to say that it was a long coach, with seats on each side, and an aisle down the centre, very like the coaches used in our suburban lines at Cape Town and Johannesburg. The only difference (and a very vital difference) was that in this German coach was a very small centre compartment, shaped like the compartments on our long-distance trains, which divided the coach into two parts. The only doors in the coach were at each end, and the smaller compartment opened by a door into each of the larger ones. In the small centre compartment were Newbold, Mackay and two others, while Ward and I were alone at the end of one of the larger compartments. The Russians were all crowded near the door of one of the main compartments, and, as War had let them into the secret, they were soon in deep conversation with the guards.

I opened our window, and found that it only dropped about fourteen inches. I endeavoured to open it further by hacking away the sash cords with my knife, whilst being apparently interested in the scenery. When the sash cords were severed it was no better. It was still snowing, and Ward and I had come to the conclusion that it would be highly dangerous "to alight whilst the train was in motion". We went into Newbold and Mackay's compartment, and found that they were just waiting for the train to go a bit slower. Occasionally we stopped at small sidings with station buildings on the right, and at the next halt of this kind we decided that we would make an attempt. We can to the conclusion that the best way to get out was feet first - a feat which could be accomplished by pulling oneself up level with the top of the window by means of a rack which ran above the windows.

Nearing our next halt, we told Newbold and Mackay what we were going to do, warning them that we planned to keep close to the side of the train and walk unconcernedly towards the van. In this way, we argued, the guards would not see us even if they glanced out of the window; and we made a point of asking the Russians to look out of the left side, and so attract every attention to that side. As soon as the train came to a standstill Newbold made a dash to the window, followed by Mackay. How they got out I don't know, but it certainly wasn't feet first. On meeting Ward below, we strolled as unconcernedly as we could down the length of the train, while on glancing back I had a vision of Newbold and Mackay clearing off at right angles to the train over fences and ditches. I swore under my breath. If the guards should by glance out of the right-hand window! I feel sure our fellow-prisoners must have done their duty nobly and managed to attract all attention to the left-hand side. Ward and I walked past the train to a level-crossing and then on to the road.

Hours seemed to pass in the covering of that short distance, and it was all I could do to stop myself from walking fast or running. We hadn't gone far down the road to the right when my heart gave a leap. The engine gave a shrill whistle. Had they seen us, or had they spotted the other two? I glanced back to see the train beginning to move. Just then we passed a Calvary and silently I gave thanks for our release. Slipping into a wood, we put as much distance as we could between the station and ourselves and then took stock of the position. The first thing was that my coat was too bright, so I took off my cardigan and wore it on top of the blue coat, which I tucked into my waist. It was raining now, but at times the sun became visible. We knew that we couldn't be far off Donaueschingen, and we made our direction to be S.E. At any rate, we moved off in that direction as fast as we could and reaching the crest of the hill we saw a river below us. We came to the conclusion that it was the Danube, and although not very wide at this point, it would be inadvisable to swim across, especially as there was a village only about a mile or so downstream. We hurried down towards the village, and, on nearing a bridge on the outskirts, Ward suddenly developed a stiff leg and I had a turned-in left foot, our theory being that we would be taken for "unfits" by the people on the bridge. They probably thought that we were mad.

So we passed over the Danube and gave a sign of relief; it was our biggest obstacle as far as we knew. We didn't care to turn round to see if we had roused the suspicions of the villagers, and so I waited until we got near a bend in the road and knelt down, pretending to fasten my boot, but really to look round. Everything seemed all right, and as soon we were round the bend we left the road and hurried through a wood. If anybody should have accosted us I don't really know what we would have done. There was really only one thing we could have done, and that was to have run for it. Looking back, we could now see the smoke and haze of a big town to our right, and made up our minds that it was Donaueschingen. Very carefully we investigated the main road before crossing it, for this time we felt sure that our disappearance must have already been notified at Eschingen, and not only would patrols be out, but in all probability those fearsome wolfhounds, which we knew were used to hunt prisoners.

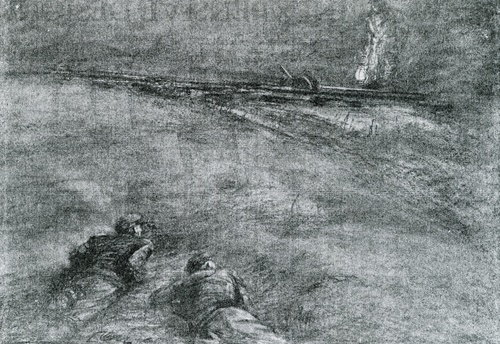

Having been on the move for about two hours, we sat down in an old quarry to take a little nourishment, carefully burying the bully tin before we moved on! Then it came on to rain again and later to snow. Making our way into a wood, we suddenly heard the baying of hounds - a sound which set us running as fast as our limbs could carry us, until, exhausted and wearied, we at last rested in a large summer house. There we found our maps practically useless. At the crossings of the paths were signposts, but we could not even find the names on our maps and we were now hopelessly at sea. Before us was a valley running due south. Reasoning that this must ultimately fall into the Rhine, we decided to follow it, and at about three o'clock in the afternoon we came in sight of a village on the opposite bank and at a junction with a large river. Climbing up the hill above the village, we found ourselves spotted by some peasants in a field below. They jabbered excitedly, but did not move. Ward's knee, in which he had been wounded, began to trouble him and the rain fell in torrents. Fearing, however, that the villagers might now have given the alarm, we pushed steadily along, and just before darkness came into sight of a fairly large town. Crouching in the darkness before we crossed the railway line that ran through the town, we suddenly found a light appearing on our right and a man coming towards us carrying a lantern. Instantly we fell flat on our faces and the man stopped only a few yards from us. I could not make up my mind whether to lie low or to get up and run, for I felt sure this fellow had seen us. All that he did, however, was to stoop down and light the railway signal lamp. He had come along the track merely to light the lamps.

Our great aim now was to get away from all signs of civilisation. No stars were visible and we had no idea of direction; we could not even see more than the bare outline of the trees near us against the snow. The cold was intense and we were wet to the skin. The only thing was to keep on the move - but in what direction?

The wind had become north-east and I thought that we might take the damp side of a tree to be the north-east, but my hands were too cold to feel anything and it was too dark to see. We gave it up as hopeless and very cautiously made our way in the direction which we thought to be south. Through woods, down banks, up inclines, the ground seemed very broken. Once we came out of a wood into what seemed to be fields. We crept along a fence, when suddenly we saw somebody and lay flat on the snow, watching this dark object showing up against the unbroken background of white. Then the object appeared to be two men, and I was sure they were moving, but I could hear nothing. How long this terror lasted I don't know, but I suppose I got so cold I could stick it no longer. I got up and crawled forward. It was a plough! We were both very amused and even more relieved. Reaching the woods again, the drip, drip of the melting snow off the trees made us very jumpy. All at once we heard footsteps and then voices; this undoubtedly - we told ourselves - was the frontier! But after a time we heard nothing more and moved forward cautiously until we came to a path which showed tracks and signs of use. Dashing across through the trees, we found ourselves in a clearing, on the side of which was a hut. We at once lay down in the snow and waited. There was no sound and no sign of life. By this time we were desperate, the cold was more than one could bear. Talking in whispers, we came to the conclusion that we must take shelter in the hut, but in case it was occupied, we decided to knock, run away and watch developments. We slowly crept round it, and, seeing no signs of life, knocked at the door and ran. Nobody came out to welcome us, so I crept up to the door again, and found that it opened to my touch. I flung it open and again ran. As this did not have any effect, we decided to enter. The hut appeared to be used by one of the woodcutters for tools and as an eating-house. It was made of rough cut logs with a bench on one side and shelves above.

We closed the door and sank down on the bench, huddled close to one another for warmth. After a few minutes I found that Ward had collapsed and I was on the verge. The only hope was to make a fire; if this wasn't done I felt sure it would be our end. It was a risk, but we had not heard any voices for some time. I found some paper under the bench and lit this in the middle of the room. In the light I gathered odd bits of wood and chips and got the fire going. I took of Ward's boots, coat and trousers, and placed these in front of the fire. He was soon feeling the benefit of the fire and his old self again. We kept drying one of each of our garments, and when, suddenly, we saw the first rays of dawn showing in the gaps between the logs, we took our belongings and cleared off into the woods.

Dawn gave us our direction and we walked due south as fast as we could. On coming to a small hollow with very steep sides, Ward found that he was not strong enough to climb to the other side. Poor fellow, he was very distressed and his knee was giving him pain. In order to save his strength we decided to keep to more level ground, which meant that we had to go east. Before long we came to a road, and, seeing some houses further down, decided to investigate.

On nearing the first house on the road, we could discern the white cross on a red shield. The Swiss coat-of-arms and probably a post office! We were too worn out to show signs of elation, but silently shook hands. Switzerland at last!

Deciding to walk through the village and continue our way south, we passed two old men and said "Tag", but they only looked at us with their mouths open. Proceeding through the village, a window opened, and a man shouted, beckoning us to stop. Deciding that we were now safe enough, we halted, and the man came out to greet us. He guessed that we had crossed the frontier and presumed we were Russian. Ward answered that we were French students from Hiedelberg who had been interned by the Germans. He was very pleased and told us that the Germans were looking for some escaped prisoners on the frontier; in fact, there was a patrol a few hundred yards along the road which we were taking. We were in a village called Bargen, and the road to Merishausen and Schaffhausen again crossed the frontier into Germany before reaching these two Swiss towns; the frontier was very irregular and Bargen was in a small corner of Swiss territory. Very sincerely we thanked him for saving us from the fate of again falling into the hands of the Germans.

Then he told us he was Douanier (Customs Officer), and would take charge of us. Taking us into his house, his wife gave us each a large bowl of bread and milk and whilst we were busy eating the wife said that we were not like Frenchmen, but had the "type Anglais!" Ward asked "What would happen to us if we were English?"

"Oh! Nothing" replied the Douanier. We then told them who we were and our adventures of the last twenty-four hours.

When we had eaten, the Douanier strapped on a belt and revolver and proceeded to escort us to the next town. We went out of his back door and across country, leaving the road some way to our left. After half an hour we reached Merishausen, where we were given some more bread and milk. The Douanier left us in charge of an old woman at the inn and after some time returned with a "diligence". We all climbed in and were seen off by the entire village. The drive was long and cold. After about an hour or more we reached Schaffhausen, where we were handed over to the police and then to a Frenchman, one Ernest Oechslin, who took us off to a barber named "Otto Blank", who proceeded to shave, shampoo and clothe us, much to Ward's annoyance; he felt very ill and only wanted to sleep. When we were "cleaned up" Ernest Oechslin took us to a hotel, where we had a tremendous lunch, and at once went to sleep. We were to be sent to Zurich, but could only go by a train leaving about 3.30 as all other trains went by the shortest route, and that was through German territory. When it was time to go I went to call Ward, but he refused to move. The police and the Frenchman were getting excited, and not until I threatened to leave him behind did he get up.

Arriving at Zurich, we were taken to the military authorities, cross-questioned, and a report made out by an old Swiss officer in English. Before he finished he British Vice-Consul arrived on the scene, and when we declined the Swiss officer's offer to intern us for the duration of the war, we were handed over to our Vice-Consul "to be repatriated as undesirable aliens".

So we were taken to a "pension", where the Vice-Consul was living with his wife, who was a Miss Palmer, of Bloemfontein; and after breakfast we went to the Consulate, where we met Sir Cecil Hertslet, Consul-General. He was a charming old man - one of the last Britishers, I believe, to leave Antwerp when we evacuated the port in 1914.

After Sir Cecil has written a despatch to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sir Edward Grey, reporting our escape, we were seen off at the station by the whole English and French Colony. Autographs were demanded until we both became absolutely tired, and I know that every button seemed to disappear from my coat.

It was on Good Friday morning that we reached Paris where, after a good bath and general clean-up at the Hotel Edward VII, we had lunch at the Embassy with Lord Bertie, the Ambassador, who was very amused at our clothes, and especially my boots. I remember how he seemed very deaf, but I remember too, how he seemed to hear anything that was of any importance - a sure sign of a true diplomat, I suppose!

Easter Monday found us in London, where we spent several hours making reports and answering questions at the War Office, and it was then that we discovered that no British officer had escaped Germany up to that time, except Colonel Van der Leur, who escaped in 1914 or 1915.

And so ended what I hope may ever remain the most eventful fifty-two days of my life.'

Having completed his 'home run', Champion spared little time in returning to the fold. In September 1916 he was attached to No. 64 (Training) Squadron and by the start of 1918 was commanding No. 69 (Training) Squadron. By war's end he had bagged a 'mention' (London Gazette 29 August 1919, refers) to go with his richly-deserved Air Force Cross. Demobilised in October 1919, he returned to his beloved South Africa to continue farming in Bloemfontein; sold together with a comprehensive set of copied records and research, including photographs of the recipient.

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Estimate

£3,000 to £4,000

Starting price

£2100

Sale 19003 Notices

Withdrawn