Auction: 19002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 486

(x) Matjiesfontein District Mounted Troop

Approximately 46 Medals were awarded to the unit, of which 29 were later returned.

'Cecil John Rhodes once said that he had only met two creators in South Africa: Himself and James Douglas Logan, the Scottish-born founder of Matjiesfontein. Representative in many ways of a grasping late nineteenth century cowboy capitalism that came to reshape and dominate the subcontinent, while holding aloft the flag of 'fair play', 'civilisation' and 'empire', Logan was in the vanguard of an accelerating expansionism at a time when the British bore few doubts about their historic mission.'

Empire, War and Cricket in South Africa, Logan of Matjiesfontein, by D. Allen, refers.

The important Queen's South Africa Medal awarded to Captain the Honourable J. D. Logan, Commanding Officer of the Matjiesfontein District Mounted Troop, who rose from humble beginnings as a porter with the Cape Province Railway Service to become the 'Laird of Matjiesfontein', a member of the Cape Parliament and what history remembers as the second of the three great benefactors and patrons of South African cricket

Queen's South Africa 1899-1902, 1 clasp, Belmont (Capt: Hon: J. D. Logan. Matjesfontein D.M.T.), note spelling of unit, extremely fine

James Douglas Logan was born at Reston, a small Berwickshire town close to the English border, on 27 November 1857. His father, James Logan, worked as a ticket clerk for the North British Railway at Reston Station and, following an education at Reston House School, Logan Jnr. was encouraged to follow in his father's footsteps and contribute in what were economically challenging times for the family. Robert Toms, writing in Logan's Way, describes a happy yet 'resourceful' childhood, recounting how the Logan family income was supplemented by poaching - something to which the young James proved more than adept:

'Mr. Logan's family in Reston were rabbit trappers,' recalled a local man many years later, 'and I remember that Mr. Logan apparently got into trouble with the police and was due to appear in court on charges of poaching. He disappeared before court proceedings and went to South Africa.'

An apocryphal story, perhaps, but an early indication of the controversial nature of a man whose destiny lay elsewhere.

A life no longer 'cabined, cribbed and confined'

Feeling confined by the strict norms of the prevalent Victorian society of the times, and hearing stories that in the Colonies there was no aristocracy and no social class - indeed rather there was money for the making for the steadfast of heart - young Logan travelled to London to ponder his next move. As the gateway to Empire, the City introduced him to stories of the rapidly expanding settlements in the Antipodes and he took work as an apprentice aboard the 437-ton sailing vessel Rockhampton on 12 February 1877, bound for Queensland with a general cargo and a number of emigrants.

Fate deals its cards

The voyage was not a smooth one. Rounding the Cape of Good Hope the ship took a battering from powerful winds and high seas, the condition known locally as 'revolving storms' - with the direction of wind changing frequently, often in an extremely erratic manner. Forced to take refuge in Simon's Town for running repairs, the enforced delay proved frustrating for Logan, more so with no specific time and date for commencement of the voyage. Ashore and contemplating his next step, it is likely that he was quickly swayed by the prosperity on show in the region, not just from the traditional primary industries of copper mining and agricultural endeavours, including wine and brandy, but also that associated with newfound gemstones, especially diamonds. Ever since Erasmus Jacobs, a farmer's boy, found a small, brilliant stone on the banks of the Orange River in 1866, the area had been a focus for those seeking to make their fortune, but things had become even more interesting in 1871 when Esau Damoense, a cook for a prospecting group, chanced upon further deposits and took them to the de Beer brothers for evaluation. This sparked a 'New Rush' of eager prospectors, the area taking the name New Rush in consequence - later changed to Kimberley.

With people and wealth came a need for infrastructure, in particular the requirements for an effective communication and transport system. Having negotiated an official discharge from duties aboard the Rockhampton, Logan found employment with the Cape Province Railway Service on 5 shillings a day and likely used his knowledge of the railways to achieve rapid advancement. Promoted to the clerical department at Salt River Station, he soon found himself serving as Station Master at Cape Town Railway Station, before being promoted to Railway Superintendent between Hex River and Prince Albert. There was just one caveat: his appointment in the remote hinterland of Karoo required him to be married within three months.Finding a wife in such a 'dry and desolate area'

Undaunted by the challenge, Logan set about finding a wife, and within three months had met and married Emma Haylett, a descendant of one of the most respected Dutch families, the de Villiers of Villiersdorp. Aged just 21 and 19 respectively, the couple moved to Karoo on 5 August 1879 where land was cheap, and Logan purchased 2,888 hectares for £400. In 1883 he decided to resign from his role with the railways, and in 1887 he began to invest in the water industry knowing that every locomotive required 250,000 litres of water to cross the Karoo. As the population increased, so the demand for water rose, with consequential conflicts between domestic and industrial or agricultural precedence. Having invested in boring machines, Logan inaugurated 'Water World' in November 1889 to significant fanfare, not just delivering the security of supplying Matjiesfontein with a surplus 50,000 litres per day, but also offering a party to hundreds of guests, mostly important dignitaries. Inaugurated by Lady Sprigg, wife of the then Cape Prime Minister, Sir Gordon Sprigg, the local media reported, 'the luncheon served in a decorated railway shed would have done justice to a first-rate London hotel.'

The Great and the Good come to visit

By the mid-1890s, the man who had taken his first footstep on South African soil with only £5 in his pocket had come a long way and was now a wealthy man. Conjuring up a little segment of his native Scotland in the desert, people vied with each other to visit this arid place where Lord Randolph Churchill 'picked bluebells in the hills,' and Olive Schreiner - the first great South African author who wrote under the pseudonym Ralph Iron - served dinner to Cecil John Rhodes in a little cottage which still stands. Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace wrote a poignant piece on the death of Queen Victoria whilst staying there, whilst General Haig gave parties in a small mess which had once been a laundry. Other notable visitors included the Duke of Hamilton, His Highness the Sultan of Zanzibar, Lord Carrington, Admirals Nicholson and Rawson and the astronomer Sir David Gill. Made J.P. in 1888 and a member of the Legislative Assembly for the constituency of Worcester, Logan was now a prominent figurehead.

The emergence of cricket in South Africa

Cricket first came to the African continent with the military between 1795 and 1802, in the earliest days of the British regime. Members of the garrison that occupied the Cape in 1806 found time to play cricket and two years later the first reference to a cricket match being played in South Africa appeared in the Cape Town Gazette and African Advertiser. As elsewhere, cricket's imperialists viewed the spread of the game as an indicator of a colony's cultural and social development. Indeed English cricketers were seen as purveyors of the 'enlightening' process in far flung corners of the Empire, including South Africa. Sir Pelham Francis Warner, M.B.E., affectionately and better known as Plum Warner or 'The Grand Old Man' of English cricket, associated South Africa's evolution with the spread of the game throughout the region:

'Step by step we have forced our way up north, and the cricket pavilions that have sprung up along our track may almost be called the milestones on the road of the nation's progress' (The Imperial Game, Empire, War & Cricket in South Africa, refers).

Logan quickly realised that association with cricket would not only be a means of keeping himself in the news but would also have a role in promoting his business interests, bringing him closer to the well-known political circles of the time. In 1888, South African cricketers had their first exposure at International level when the Castle Line packet Roslin Castle arrived at Cape Town carrying the first English cricket team - known as Major R. G. Wharton's team. The motley English group comprised 7 amateurs and 7 professionals, and of the 20 matches played on the tour, only 2 were in the 11-a-side format, subsequently recognised as the very first First-Class cricket matches played in South Africa.

English Cricket 1891-92; an opportunity cometh

Amongst cricket aficionados it is a well-known fact that from 1891-92 England sported two separate national teams which engaged in two different touring regions. While the first, led by W. G. Grace, played South Australia at Adelaide on 20 November 1891, the second, led by Surrey Amateur Walter Reid began with a game against Western Province at Cape Town on 19 December 1891.

The team under Grace was known on the Australian tour as 'Lord Sheffield's Team', the entire tour being personally sponsored by Henry Holroyd, 3rd Earl of Sheffield. Recognising the English players in South Africa lacked a sponsor, Logan took the decision to step into their financial void and proceeded to loan the team £1000 towards the cost of the tour 'in the interests of cricket'. Edward 'Daddy' Ash, the tour secretary, offered to repay Logan 30% of the tour profit, but Logan requested the return of his money 'with reasonable interest'. In this manner friendship was often borne, and by the early 1890s it became a fashion for touring cricketing sides to enjoy a peaceful interlude as Logan's guests, no doubt utilising the full-sized cricket square at Matjiesfontein laid out by their host at a personal expense of £800. On the other hand, in this instance, Logan showed the businessman within when the loan was not repaid due to the unprofitability of the tour. In Australia it had been the Earl of Sheffield who had taken a £2000 'hit' from good old English willow. In South Africa, Read and Ash were arrested and made to face the court; Logan was not a man to roll over and accept defeat in any sphere, and certainly not in financial matters.

Colonial arrogance and opposition

Around 1893, Cecil Rhodes mooted and then supported the idea of the first ever South African cricket tour of England, projected for the following year. Seizing opportunity, Logan pledged £500 as financial support and offered his cricketing facilities at Matjiesfontein, however he imposed two caveats - that the 'talented' Afrikaans cricketer Krom Hendricks be selected and that his friend Harry Cadwallader be nominated team manager.

Revealingly, after meeting Cecil Rhodes at Oxford University in March 1895, Pelham Warner recounted a conversation about cricket and the debate surrounding Krom Hendricks. Referring to the reaction afforded the Australian aboriginal team that had toured England some years earlier, Warner's account displays the attitude and influence of Rhodes in the 'selection process' of early South African teams:

'I was fortunate enough to sit next to Rhodes, and the conversation turned on the first visit, during the previous summer (1894), of a South African team to England. Rhodes had had a good deal to do with the financing of this side, and he remarked: 'They wanted me to send a black fellow called Hendricks to England.' I said I had heard he was a good bowler, and he replied: 'Yes, but I would not have it. They would have expected him to throw boomerangs during the luncheon interval.'

Logan withdrew his offer of financial assistance for the tour.

Promoter for the 1898-99 tour

Following the early success of the 1895-96 England tour of South Africa which was rudely interrupted by the Jameson Raid on the Transvaal, Logan took on the role of promoter for the 1898-99 tour, utilising his decidedly enhanced influential stature and guaranteeing all expenditures. Any profits made on the tour would go to the South African Cricket Association.

The England squad arrived at Cape Town aboard the Scot on 20 December and quickly found their feet - of the 24 matches played, the English cricketers were successful in 16, including both tests at Johannesburg and Cape Town. Logan, described rather critically by author Dean Allen as 'A keen but untalented player', turned out for the local team in two exhibition games at Kimberley and Matjiesfontein. However, these would not be the only occasions on which Logan would step up to the crease; in his First-class career he represented South Africa on four occasions, notching up 100 runs over 8 innings with a high score of 35. His bowling statistics afforded 20 runs from 18 balls, without wicket.

The Logan Cup

Following the match at Kimberley, in March 1899, Logan accompanied the England team north on a 55 hour-long journey to Rhodesia, the railway having been extended as far as Bulawayo. Wishing to make his mark on Rhodesian cricket, Logan requested Martin Bladen Hawke, 7th Baron Hawke, in charge of the England team, to purchase a suitable cup at Logan's expense upon the latter's return to England. In due course, the imposing 2 feet 6 inches tall solid silver trophy arrived and was inscribed:

'Presented by the Hon. J. D. Logan, M.L.C., to the Rhodesian Cricket Association in commemoration of the first visit of an English team of Lord Hawke's, March 1899.'

Priced at 100 guineas, the trophy was named the Logan Cup and is used for the premier First-Class domestic championships in Zimbabwe to this day.

The Boer War - not cricket!

With the war in South Africa almost a certainty, Logan was forced to cancel a reciprocal visit to England by a South African team in 1900. Instead of raising a team of cricketers, Logan raised a company of mounted rifles at Matjiesfontein on 1 January 1901, under his own command and supported by a single further officer, Lieutenant Hugh Smith. Making his land available as a British base - which stationed up to 12,000 troops at one point - Logan's men guarded the Matjiesfontein railhead which assumed considerable strategic importance. Lord Roberts used it to launch his advance north and break the siege of Kimberley, whilst it was used on an almost daily basis as a valuable supply line. A field hospital was even commissioned 'Logan's hotel' with a machine-gun mounted on its turret.

As for his own part in the ensuing operations, an accompanying copied roll for the Matjiesfontein District Mounted Troop reveals Logan's annotation by his own name: 'Took part in Battle of Belmont, by permission of Lord Methuen'; see below for relevant - original - documentation regarding his part in the conflict.

As the balance of war began to swing towards the British, Logan reopened his pitch for a tour to England scheduled for the summer of 1901. Having assembled a team, with Murray Bisset, a close acquaintance, secretary and skipper of the Western Province Cricket Club, agreeing to Captain the side, the tour was officially announced by Hawke in The Times on 1 December 1900. It was not well received.

The announcement sparked off a raging debate about the propriety of such a venture at a time when the youth of both countries were opposed in mortal combat. Just a month previous, the Australian Test Cricketer John Ferris had died of typhoid at Durban whilst serving with the British Army. He was just 33 years of age. That same year had resulted in the loss of the England Test Cricketer Frank William Milligan, who had stayed on in South Africa after the 1898-99 tour and served as a Lieutenant under Colonel Plumer. A talented all-rounder who bowled at a lively pace, who excelled at the Gentlemen Vs Players at the Oval in 1897 - scoring 47 in each innings and snaring 2 wickets for 3 runs in the Players' second innings - he was killed in action at Ramatlabama, aged 30. A further 10 First-Class cricketers would go on to lose their lives in the war, including Cecil Boyle and Dudley Forbes of Oxford University and Charles Hulse of the M.C.C.

Arthur Conan Doyle was one of the most vociferous objectors to the idea of cricket being played at such a time. Writing in the Spectator, he voiced his misgivings in no uncertain manner:

'Sir, It is announced that a South African cricket team is about to visit this country. The statement would be incredible were it not that the names are published, and the date of sailing fixed. It is to be earnestly hoped that such a team will meet a very cold reception in this country, and that English cricketers will refuse to meet them.'

Despite this, it was subsequently determined at Lord's by representatives of the English counties and M.C.C that:

'If the South African team came to England in 1901, the matches with the First-Class Counties should rank as First-Class, and consequently be counted in the averages.'

The conclusion was essentially a final stamp of official approval for Logan's England venture. Wisden later remarked that 'a good list of matches was arranged for the South African team'.

Selection of the touring party

If the timing of the tour was, in hindsight, inappropriate, the personnel which comprised the touring party were selected with considerable care and foresight, whereupon an ideal mix of 'socialite gentlemen cricketers' and genuinely 'skilled players' was arrived at. The list included Jimmy Sinclair and Barberton Halliwell, described by Wisden as 'one of the best of the early wicketkeepers from South Africa'. He was also the first keeper to put raw steak in his gloves to protect his hands. The team also included Johannes J. Kotze, an Afrikaner known as 'Kodgee', and one of the fastest bowlers to appear in First-Class cricket.

Logan made a personal statement by including his son James in the party of 14, although he had no experience of First-Class cricket at that time. However, in a masterstroke of diplomacy, Logan ensured the team colours for the 1901 tour were red, blue and orange, the identical colour scheme of the Queen's South Africa Medal riband.

The 1901 tour

Arriving at Southampton on 3 May, Logan's team went on to play 25 matches, 15 of which were accorded First-Class status. Of these, the tourists won 5 and lost 9, while the game with Worcestershire was tied. A highlight was the match against Cambridge University at Fenner's from 10-12 June, where the South Africans knocked up a mammoth total of 692, with centuries by Maitland Hathorn (239 runs) and Bertram Cooley (126 runs n.o.). At that time the highest total in South African cricket history, an easy victory was achieved by an innings and 215 runs.

Contrary to the reception accorded by Conan Doyle, the South Africans were well received in England and the hospitality was generous. The tour fulfilled Logan's desire to lead a team to the home of the 'Empire Game', and in gratitude he presented Hawke with a silver salver as 'a token of gratitude'.

Invitation to the 1902 Coronation

In July 1902, Logan and his wife were invited to attend the Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra at Westminster Abbey, followed by several social rounds including an invitation to the Colonial Reception at St James's Palace. It represented the pinnacle of his social elevation.

A man of many parts, Logan was an expert photographer, an amateur magician and member of the Magic Circle, a dentist, horse-breeder, boxer and a keen sportsman. A shrew businessman, he owned a string of properties and estates in South Africa, but above all, it is perhaps his contribution to South African Cricket for which he is most revered and remembered fondly.

James Douglas Logan died at Matjiesfontein on 30 July 1920, the notification of his death being appropriately listed in the Wisden obituaries of 1920.

Sold with an impressive folder of original documentation, including:

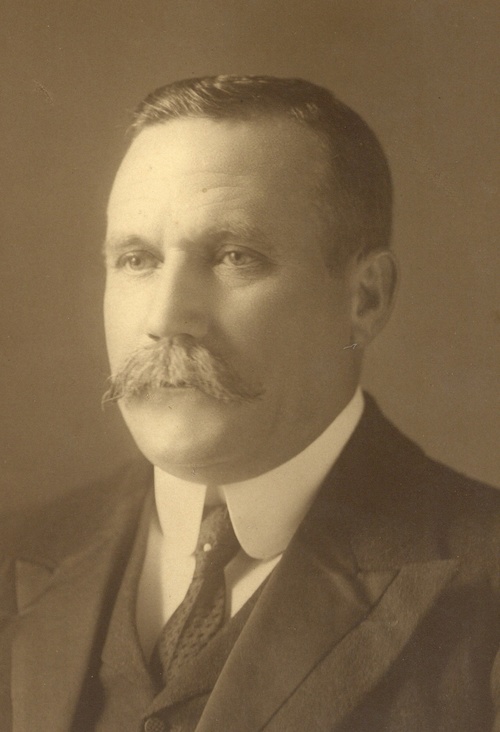

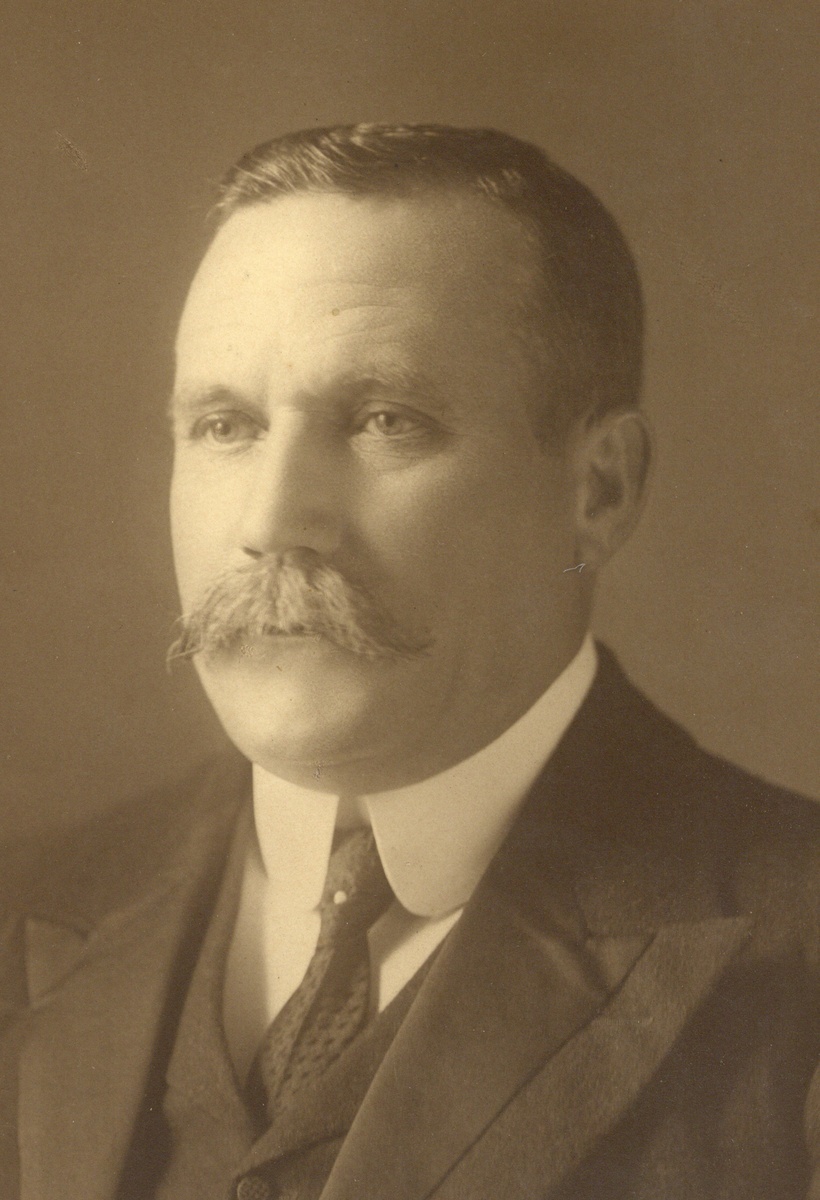

(i)

A large portrait photograph of Logan and three-quarter length photograph of him in formal civilian clothing.

(ii)

A warrant appointing Logan Justice of the Peace for the District of Worcester, dated 11 January 1888.

(iii)

A hand-written letter in original envelope of transmission from Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, to Logan, dated 25 January 1901, thanking him for military assistance and praising him personally:

'I know there is no more loyal man in the Colony, or none more able and willing to help.'

(iv)

A telegram from Logan to his daughter from the battlefield at Belmont:

'We had a grand fight, mile and a half Cape Town side of Belmont yesterday morning and we fought splendidly, but I am afraid our loss killed and injured at least 150. Artillery did splendid work - that and gallant charge of our infantry up the Hill was sight never to be forgotten.'

(v)

A permit to proceed to Cape Town for Miss G. Logan, dated 9 January 1901; A Road Traffic Pass giving Miss Logan authority to proceed by road 'anywhere in the neighbourhood of Matjiesfontein & beyond the out-posts', dated 16 March 1901; A Dock Pass for Miss G. Logan, dated 17 April 1901; a further pass giving permission for Logan and his family to proceed from Kimberley to Bulewayo.

(vi)

A photograph of 'Logan's Pet' by E. D. Edgcome, Beaufort West - a machine gun named after Logan, possibly the one positioned in the turret at 'Logan's hotel'; a further photograph annotated to reverse 'Hon. J. D. Logan bidding adieu to General Sir Chas. Warren at Matjesfontein' (note spelling).

(vii)

An original hand-written letter addressed to 'The Hon: J. D. Logan, Matjiesfontein, Cape Colony', by General Douglas Haig, later Field-Marshal, dated 2 Dec. 1914:

'Dear Mr. Logan,

I was much touched by your kind telegram and thank you very much for your kind congratulations which I very much appreciate.

This should reach you about Christmas time. I well remember one happy one spent with you all at Matjiesfontein and how kind you were to the troops and us all. Please accept my heartfelt wishes for a Happy Xmas.

Believe me, yours very truly,

D. Haig.

(viii)

A Post Office Telegram from General Haig, dated 18 December 1915:

'Many Thanks, Kind Congratulations, General Haig, Decr 18th 10am.'

Reference sources:

Empire, War and Cricket in South Africa. Logan of Matjiesfontein, Dean Allen.

https://www.cricketcountry.com/articles/james-douglas-logan-the-laird-of-matjiesfontein-684121

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium.

Sold for

£2,300

Starting price

£800