Auction: 18003 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 445

The unusual - and fascinating - Great War 'Secret Service' group of three awarded to Captain E. Knoblock, Intelligence Department, a distinguished Harvard-educated playwright and literary figure; posted to Athens in November 1917, Edward Knoblock rendered invaluable service to the British Legation by working to maintain Greece's neutrality during a critical phase of the war

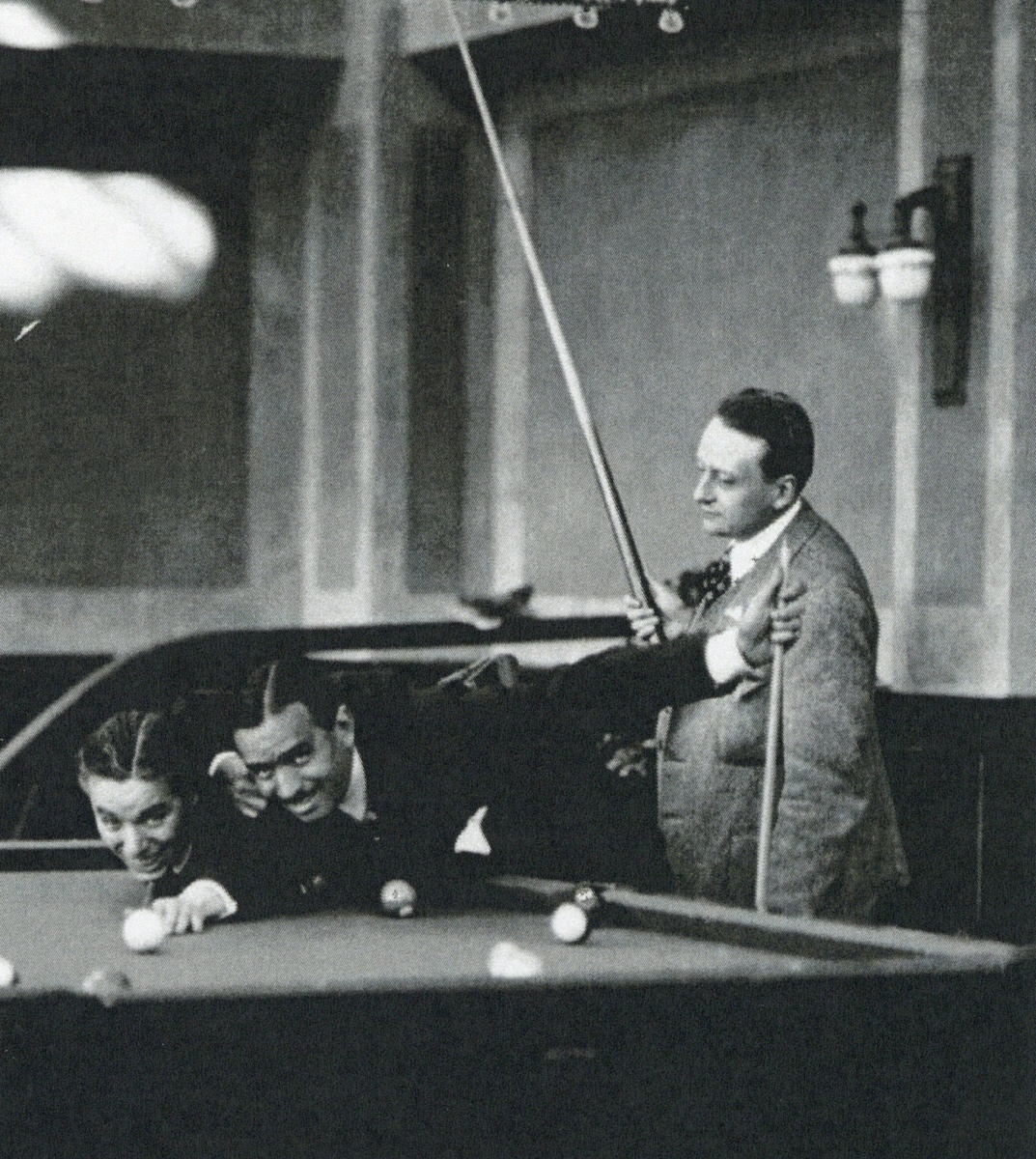

Asked by Douglas Fairbanks to write the film scripts for The Three Musketeers (1921) and Robin Hood (1922), Knoblock co-authored a dramatisation of The Good Companions (1931) by J. B. Priestley and an adaptation of The Edwardians (1937) by Vita Sackville-West. A consummate socialite and bon vivant, his autobiography Round the Room (1939) is a highly entertaining read

British War and Victory Medals (Capt. E. Knoblock.); Greece, Kingdom, Order of the Redeemer, 5th Class breast Badge, gold, silver-gilt and enamel, the last with slight hairline cracks to the white enamel and minor chips to reverse, otherwise very fine, generally very fine or better, with the recipient's green Intelligence Corps flashes; Harvard Delta Cappa Epsilon Society Silver Medal, 42mm in diameter, engraved 'E. G. Knoblauch, '96'; Harvard Signet Club Silver Medal, 38mm in diameter, engraved 'Edward G. Knoblauch, '96', good very fine, all housed in a velvet-lined leather case (3)

Order of the Redeemer, London Gazette 9 November 1918.

Edward Knoblock was born at 60, West 17th Street, New York City in April 1874, grandson of the German architect Eduard Knoblauch. Following the sudden death of his father, an investment banker, his family spent over two years in Berlin, where he regularly visited the theatre. In his teens he was determined to become a playwright, despite his father's dying wish that he should take up architecture. Gaining a place at Harvard, he studied Moliere's comedies in addition to Homer, Euripides and Shakespeare. He was a devoted member of Harvard's Delta Kappa Epsilon Fraternity (Medal). Founded in 1851, this exclusive society boasts six American Presidents among its alumni - including both Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt - as well as J. P. Morgan and Cole Porter. Neil Armstrong even planted its flag on the Moon. Today it remains highly influential, offering the largest scholarship endowment of any Delta Kappa Epsilon Fraternity. Knoblock also joined Harvard's Signet Society (Medal), whose alumni include Leonard Bernstein and T. S. Eliot.

On graduating with a B.A. degree in 1896 Knoblock was elected "Ivy Orator of the Class of '96", which entailed delivering a humorous speech. He then embarked on a remarkable literary career. After working in Paris for a few years, he settled in London at 17 Red Lion Square, evolving a close relationship with the Kingsway Theatre. One of his earliest plays, Kismet (1911), was to prove his most successful. Set in Baghdad, Kismet was a Middle Eastern fantasy that told the story of a poet, his daughter, a prince, and a wicked wazir. It ran at the Garrick Theatre from April 1911 to January 1912, and in 1953 was turned into a popular Broadway musical. Milestones (1912), which Knoblock wrote in collaboration with English playwright Arnold Bennett, was an unsympathetic portrayal of the English aristocracy in the midst of social change. It reached over 600 performances at the Royalty Theatre. Knoblock's other Broadway hit was Marie-Odile (1915), a drama about the Franco-Prussian War.

Greece - a sartorial debacle

Ironically, Knoblock's most memorable comedy was not something he wrote for the stage, but - as is often the case with funny people - a catalogue of errors of which he was the hapless victim. In August 1914, Knoblock was determined to join the Army but his doctor prevented him as he was still recovering from an operation. A superb linguist, he offered his services to the War Office as a translator but his application was mislaid. Assigned a clerical role at the Indian Secret Intelligence Service, he approached his friend Compton Mackenzie, a prominent literary figure who had been appointed Director of Military Intelligence in the Aegean, in the hope of better work. Mackenzie wangled Knoblock a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve; Knoblock excitedly bought his naval uniform and sword. It was then realised that as he was still an American citizen, Knoblock was ineligible and would have to join the Royal Naval Air Service instead. He duly added the "woollen eagles" to his tunic. Just before sailing for Greece he heard of his commission in the General Service Branch (Army) of the Intelligence Department, which would not be gazetted until after he had left. Just to be sure, he took with him both his army and R.N.A.S. uniforms and swords. Greatly amused, Compton Mackenzie penned the following sonnet:

'To Second-Lieutenant Edward Knoblock, on receiving a Commission for the due adornment of which he had prepared himself with every known uniform.

Knoblock, from Salonika's waspish swarm

We bid thee welcome to this Syriot Isle:

And welcome too the military style,

The cap pressed grimly down against the storm,

But most the green tabs of thy uniform;

That uniform which thou so long awhile

Hast kept with others in a varied pile,

Wherein thou even hadst a British Warm.

On whom wilt thou bestow that Naval sword,

To whom present the anchor on thy cap,

To whom that woollen bird? And who'll afford

That golden lace upon thy shoulder strap?

The Army and the Navy throng thy shelf,

Thou art an expedition in thyself.'

To avoid repetition of such incidents, Knoblock became a British subject in 1916. It was then that he anglicised his name, for he had been christened 'Edward Knoblauch' and spoke perfect German. His Commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Intelligence Department was largely due to Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming, head of M.I. 6, who interviewed Knoblock in London. Smith-Cumming had lost a leg in a car accident and wore a prosthetic limb. In his entertaining autobiography Round the Room (1939), Knoblock recalled the meeting:

'To test the nerves of applicants for jobs in his department, he would sit and talk casually about the various duties and suddenly pick up a sharp paper-knife and jab it up to the hilt through his trousers and into his artificial leg. If the applicant winced, the Skipper would say: "Well, I'm afraid you won't do." Luckily I was warned about this beforehand, so never turned a hair - which evidently pleased him. But I hadn't played quite fair, I'm ashamed to say. I'm sure I should have jumped if I hadn't known what he was going to do.'

Knoblock arrived at Athens in early November 1916. Working under Compton Mackenzie at the British Legation, he became deeply involved in Greek politics. For months, the Germans had been doing everything they could to win Greece over to their cause. Pro-German demonstrations were held almost daily; since the Greek King was married to the Kaiser's sister, the Allies had every cause for concern. Knoblock was present at several meetings with the Greek Government, in which Britain wished to be assured of Greece's neutrality.

The French, true to form, lay their battleship Provence alongside Piraeus harbour and landed a party of Marines. The French Admiral called on the Greeks to 'give up their arms so as to prevent possible bloodshed.' At 11.35 p.m. on 1 December, the French Marines were fired upon by Greeks stationed near the Acropolis. The British Legation was besieged for two days until a truce was negotiated. Knoblock later reminisced:

'The English ladies behaved with the utmost calm and courage. One of them stepped coolly on the balcony while the men were firing at the Legation and told them in very bad Greek to "stop it at once". Sir Francis Eliot, who was the Minister, I saw, myself, walk out of the Legation, as a dozen or so Greeks started levelling their rifles at him. He drew The Times from his pocket and waved it at them as if to brush away flies. They stared amazed, dropped their rifles and ran. So much for the power of the Press.'

The maintenance of Greek neutrality was pivotal to Allied prospects in the Eastern Mediterranean. German and Austrian U-Boats, which sank numerous Allied vessels in the Aegean, were acting on the information of German agents based in Greece. If Greece had entered the war on Germany's side, the British counter-espionage operation would have been far less successful. Knoblock played his part in this operation, and was serving aboard the mail boat Red Breast when it sank a German submarine in July 1917. Red Breast's Captain received the D.S.O. Knoblock's own award of the Greek Order of the Redeemer, 5th Class, was announced in the London Gazette on 9 November 1918.

Given leave in early December 1917, he went immediately to London where his plays were regularly performed. On 5 December, 19 German Gotha bombers and two Riesenflugzeuge attacked London in waves. Casualties were light but over £100,000 worth of damage was caused, mostly in Holborn and the West End. Knoblock's plays did much to raise people's spirits, as he later reflected in Round the Room:

'The actors and actresses, I must add, behaved with remarkable self-control during these attacks. The leading man always stepped forward and told the audience that anyone wishing to leave the theatre would kindly do so at once. But as no one ever did, they proceeded as if nothing were happening. One night, during a very heavy bombardment, Marie Löhr acted with conspicuous pluck. It was the first night of a play and she had a very difficult part to perform. In spite of all the bangs and crashes she never turned a hair. At the end of the evening the audience cheered her.'

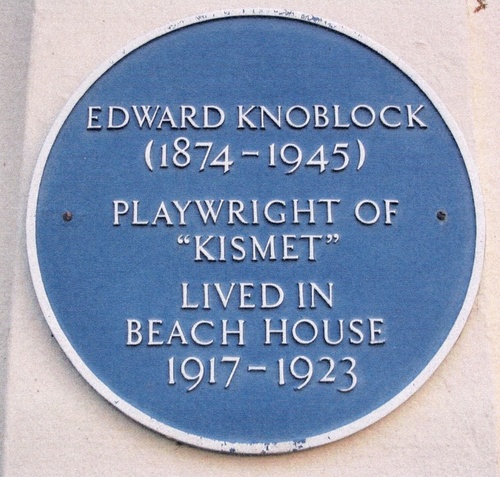

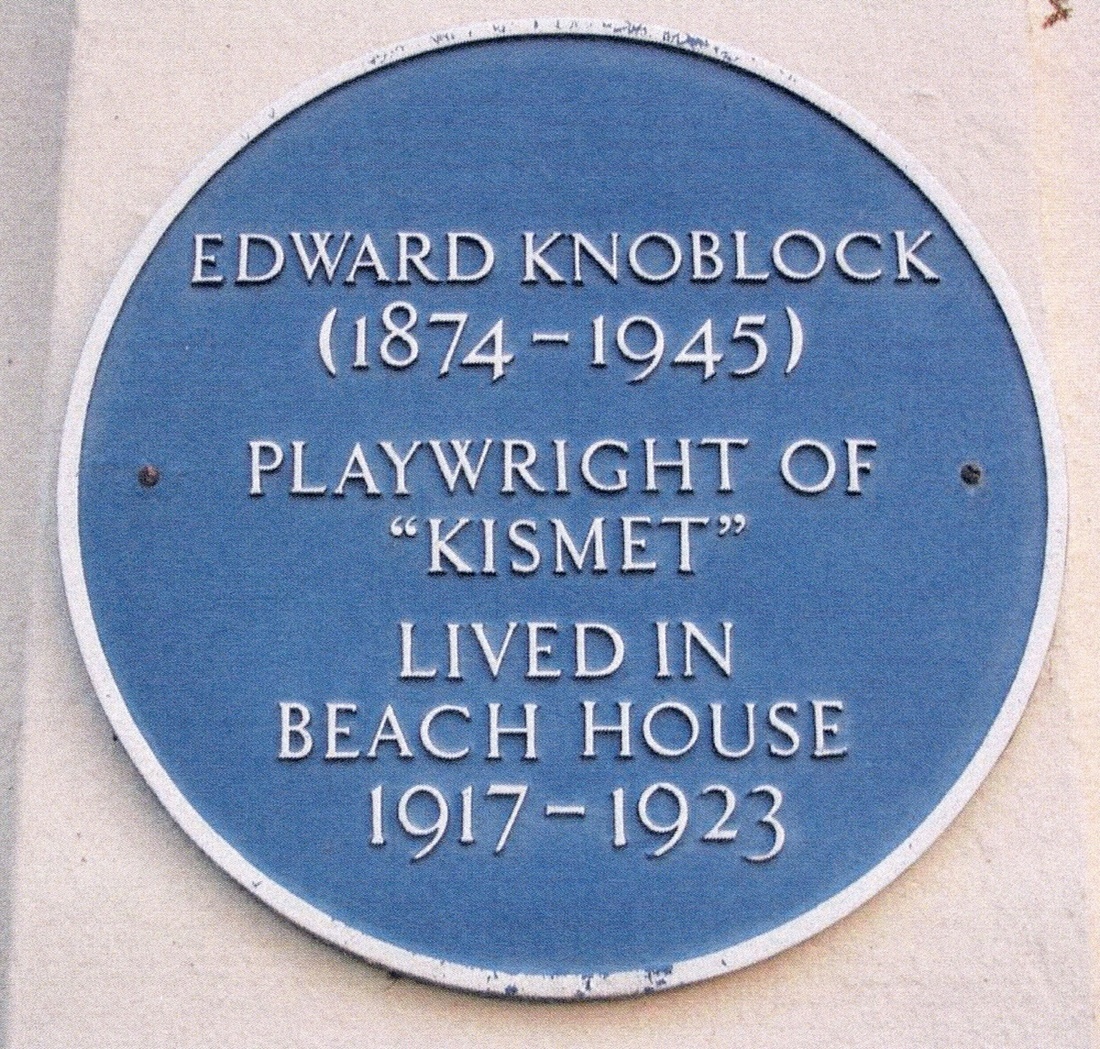

The success of his plays enabled Knoblock to get a bachelor's apartment at Albany. There he entertained numerous society guests such as Gerald du Maurier and the painter John Lavery. He also became a member of Pratt's and the Beefsteak Club. Spending the rest of his leave in Brighton with the actor Robert Lorraine, he found a neglected Regency house near Arundel and bought it on the spot. With its magnificent sea views and parkland, Beach House was to be his obsession for the next seven years. It now bears his Blue Plaque.

'All for one, one for all!'

At the war's end, Knoblock's fame reached its zenith. Increasingly in demand as a writer, he was commissioned by the film company of Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford to write the scripts for The Three Musketeers (1921) and Robin Hood (1922). Dividing his time between London and Hollywood, he worked on the films Mumsie (1923) and Speakeasy (1929); his other film scripts included Love Comes Along (1930) and Knowing Men (1930).

Knoblock collaborated with the most renowned authors of his day. In 1931 he worked with J. B. Priestley on a dramatization of The Good Companions (1931). He then adapted the novel Grand Hotel (1931) with Vicki Baum, Evensong (1932) with Beverley Nichols, and The Edwardians (1937) with Vita Sackville-West. He wrote nearly forty plays in all.

During the Spanish Civil War Knoblock was sympathetic to the Republican cause, allowing Basque children evacuated from their homes to stay at Beach House. Many of these children had fled from the Luftwaffe's bombing campaign, an atrocity which enraged Knoblock; they were largely cared for by local volunteers. During the Second World War, Beach House was used by the Air Training Corps.

Knoblock died on 19 July 1945 at his sister's London home, 21 Ashley Place. He never married; sold with an extensive file of cross-referenced research, copied MIC, a copy of E. Knoblock's autobiography Round the Room (1939), and a copy of his novel Inexperience (1941).

Recommended reading:

Jeffery, K., MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1945 (London, 2011).

Knoblock, E., Round the Room: An Autobiography (London, 1939).

Knoblock, E., Inexperience: A Novel (London, 1941).

Knoblock, E., Kismet, and Other Plays, with an Introduction by John Vere (London, 1957).

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp02582/edward-knoblock?search=sas&sText=edward+knoblock

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,100