Auction: 18001 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 580

(x) THE UNIQUE CIVILIAN'S G.C., G.M. GROUP AWARDED TO RICHARD BYWATER (1913-2005)

'In order that they should be worthily and promptly recognised, I have decided to create, at once, a new mark of honour for men and women in all walks of civilian life. I propose to give my name to this new distinction, which will consist of the George Cross, which will rank next to the Victoria Cross, and the George Medal for wider distribution.'

H.M. The King announces the creation of the George Cross (G.C.) and George Medal (G.M.) in a broadcast to Britain and the Empire on 23 September 1940; the Royal Warrant was initiated the following day.

The decorations were to reward 'acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger'. The G.C. has since been awarded directly on 163 occasions, around half those awards being of a posthumous nature; as in the case of Malta in 1942 - and more recently the Royal Ulster Constabulary - the decoration may be awarded collectively.

The G.C. and G.M. were intended from the outset to reward civilian bravery, but as many members of the armed forces were engaged in bomb and mine disposal - and other relevant - operations, they too became eligible; as a result the vast majority of the first 100 awards of the G.C. were made to members of the armed forces.

Of the 163 direct awards of the G.C. made to the present day, around 50 have been bestowed on civilians but only one of them has also been awarded the G.M.: Richard Bywater.

In that respect - and not forgetting H.M. The King's intention to create 'a mark of honour for men and women in all walks of civilian life' - his unique achievement constitutes an important chapter in the history of the George Cross.

Sold by Order of a Direct Descendant

'One fuze, Bywater judged, was in such a sensitive condition that it was too dangerous to be carried to the destruction site. He knew of two instances in which men trying to handle such a fuze had been blown to pieces. But to destroy the fuze inside the factory would cause enormous damage.

Selecting a location a short distance from the building, Bywater had an iron safe placed there with plenty of sandbags around it. Then, having sent all his colleagues out of the danger area, he carefully picked up the fuze, tip-toed across the grass and gently placed it in the safe. The sandbags were piled on, everyone withdrew out of range and the fuze was detonated.'

His obituary notice in The Daily Telegraph, 8 April 2005, refers.

The unique civilian's G.C., G.M. group of five awarded to Richard Bywater, a Factory Development Officer for the Ministry of Supply, who was twice decorated for extraordinary acts of gallantry at the Royal Ordnance Factory, Kirkby, near Liverpool

His hitherto unpublished account of his wartime experiences refers to his early fears of a major catastrophe:

'I had had a strong premonition over the months leading up to the event that there would be a terrible explosion on Group 3 involving Fuze Mine Anti-Tank and I had conditioned myself as to what I could do in such circumstances. After all, I had known this fuze from its birth at Woolwich Arsenal and had seen its violence in the proof-yard at Woolwich. So when the event occurred it was quite matter of fact for me to say, "Leave it to me, I will clear up the mess." '

He did.

When on being invested with his subsequent award of the G.C., His Majesty The King asked him how long it took to make the factory safe. "I told him we were busy for three days because there were 12,000 fuzes in danger of exploding." His Majesty shook his hand and told him he "was a very brave man."

Brave indeed for a stench of death pervaded throughout his magnificent work in clearing tons of lethal - damaged - ordnance in February 1944: some of the first sights to greet him on entering the danger zone were 'someone's oesophagus lying on the cleanway' and a pair of detached legs under a work bench.

His repeat performance under similar circumstances in September 1944 - for which he was awarded the G.M. - was in his view even more perilous. It was certainly more protracted, the clearance operation taking three months and latterly requiring Bywater to drive 'blind' in a modified bull-dozer tank.

It is perhaps not surprising that by the time of his departure from Kirkby, Bywater readily admitted to his pockets being crammed with smoking paraphernalia: 'I could only get satisfaction with Capstan Full Strength or Senior Service cigarettes, or full-strength pipe tobacco.'

(i)

George Cross (Richard Arthur Samuel Bywater; 26th September 1944), with its Royal Mint case of issue

(ii)

George Medal, G.VI.R. (Richard A. S. Bywater, G.C.)

(iii)

Coronation 1953

(iv)

Jubilee 1977, with its card box of issue

(v)

Jubilee 2002, in its named card box of issue, all but the last mounted court-style as worn, contact wear and bruising, otherwise very fine (5)

G.C. London Gazette 26 September 1944:

'For outstanding heroism and devotion to duty when an explosion occurred in a factory.'

G.M. London Gazette 18 September 1945. The joint citation states:

'An explosion occurred at the Royal Ordnance Factory, Kirkby, during the filling of highly dangerous ammunition. The night was exceptionally dark, there was no moon, and it was raining heavily. The major explosion was followed by others. Almost all lights were extinguished and soon the only illumination in and around the shattered bomb strewn building was given by the fires which broke out.

The morale of the Factory staff was superb. All the operatives were aware of the dangerous nature of the work and immediately the noise of the explosion was heard, rescuers ran from all the near-by buildings. Girl operatives, who had made their escape from the building, returned to bring out their injured friends. The Factory Fire Brigade were on the spot within a matter of minutes and ran their hose into the building. Whilst the fires blazed and bombs continued to explode, the injured were brought out and desperate attempts made to release a trapped man. They continued until the Assistant Superintendent, who was in charge in the absence on leave of the Superintendent, ordered everyone to leave the building and take shelter behind the mounds. The responsibility laid upon Mr. Denny was heavy, but his decision was justified, as in a few minutes another explosion brought down more wreckage. It was nearly daybreak when a pile of bombs in their wooden crates, crushed beneath the fallen roof, was seen to be on fire and out of reach of the firemen's hose. The fire was gaining and, had it taken hold, the consequences would have been disastrous over a wide area of

the Factory.

Mr. Denny entered the building alone. He sought some way of getting at the flames and having found this, came out and explained the position to Forbes and Topping. Without hesitation the two men volunteered to enter the building and tackle the fire from within at the proposed angle and range. The three men cautiously groped their way into the wrecked building. Standing among the damaged ammunition, which the rush of water was sufficient to disturb, with consequent risk of detonation, they brought the fire under control and completely extinguished it.

Byron, Christian and Hankin took their hose into another part of the wrecked building. They showed devotion to duty and voluntarily exposed themselves to the danger of death or serious injury.

Mr. Gale, who was on leave when the explosion occurred, returned immediately. A preliminary survey was made and a scheme, evolved by the Superintendent. It was carried successfully into effect mainly through his initiative and leadership. He organised and thoroughly tested the safety precautions, was present a considerable part of every day when work was in progress and no fresh step was taken until he had personally assured himself that the methods were as safe as his knowledge and ingenuity could make them. By his coolness, ability, courage and inspiring leadership, Mr. Gale completed a unique and terrifying salvage task without a single casualty.

Bywater, Edwards, Fitzmaurice, Murdoch, Panton and Rowling formed the team of volunteers who cleared the wrecked building. In a task presenting vast problems they displayed courage and co-operation of the highest order. The ammunition which had caused the accident was anti-personnel and anti-disturbance, and the fuzed time-bombs, scattered over and under the debris, made clearance nearly impossible by detonating without warning and in an absolutely unpredictable manner. A constant risk was the movement of wreckage and any one member of the team could, by ignorance, negligence or a moment's carelessness endanger the lives of the others. The high standard of the team work at Kirkby is shown by the fact that during the clearance operations there was no casualty.

All members of the team, under the leadership of Mr. Gale and Mr. Denny, showed high courage and devotion to duty in volunteering for and carrying through over a period of three months, so arduous, unpleasant and dangerous a task.'

Richard Arthur Samuel Bywater was born in Birmingham on 3 November 1913, the youngest of six children. His father Walter worked for the Austin Motor Company.

Young Richard - who was educated at King's Norton Grammar School and Birmingham University - once recalled how his chemistry teacher had told him that he would never pass an external examination in Chemistry. Yet he took a First at Birmingham and was offered a post-graduate scholarship in the university's research department. Having then gained his Master's degree, he was appointed chief chemist for Boxfoldia Limited in 1936.

Hostilities - Battle of Britain - Blitz

Shortly before the outbreak of war, Bywater became a technical assistant at the Royal Filling Factory at the Woolwich Arsenal and his subsequent attempt to join the Royal Air Force was refused on the grounds he was in a reserved occupation. Back at Woolwich he was placed in charge of the experimental section and, in the summer of 1940, he was appointed manager of the fuze section. The pressures of working in such a dangerous environment were quickly felt. Bywater unpublished wartime memoir takes up the story:

'I spent two or three weeks down at QFCF4 (Quick Firing Cartridge Factory) which had only recently been reopened. Apart from cartridge work they also produced smoke bombs. I found the time well spent particularly as the foreman Mr. Thomas was quite amiable and freely gave what information he could. I learnt quite a lot from him. One day he asked me if I smoked, to which I replied, "only occasionally - packet of ten would easily last a week." He laughed and replied, "I'll bet within three months you will be completely hooked." He was so right and by the time I left Kirby I sported two of three pipes and could only get satisfaction with Capstan Full Strength or Senior Service cigarettes, or full-strength pipe tobacco.'

With the Battle of Britain reaching its climax, and the onset of heavy enemy bombing, Bywater was greatly impressed by the cheerful stoicism of the local population. On one occasion, walking past a row of badly damaged shops, he noticed a boarded-up barber's shop displaying a large sign: 'We may have had a close shave but we can still give you a good haircut.'

Of Battle of Britain day itself - 15 September 1940 - Bywater recalled:

'The sky was filled with planes madly manoeuvring, Spitfires diving out of the light to attack, planes falling to earth, the sky seemingly full of parachutes. It was a scene that film makers could not possibly reproduce. All the PAD workers were stood on top of the mounds which protected the air raid shelter cheering madly as planes spiralled to the ground and parachutes floated down in more leisurely fashion … One bomber had landed in the coal bunker outside my jurisdiction, and several German airmen landed nearby, mostly fatally injured. One German told his captors (I think they were the gate guards at the back gate near the coal bunkers) that they had been told there would be no defence in the air - all the Spitfires had been destroyed.

Another German whose parachute had failed to open crashed through the roof of one of the fuze filling buildings and smashed through a strongly constructed assembly table. Luckily for me an R.A.F. officer was quickly on the scene and did the necessary. The German Officer's legs were just like putty - he must have landed feet down on the table. The R.A.F. Officer searched his clothing but all he found was an Iron Cross and a condom' (ibid).

The Royal Ordnance Factory, Kirkby, near Liverpool

Towards the end of 1940, the Blitz forced the Royal Ordnance Factory to move to Kirkby, north-east of Liverpool, where Bywater became Factory Development Officer of a new complex which had cost £8 million: its 2,000 workers - who operated in three shifts around the clock - turned out shell, mortar and 150,000 anti-tank fuzes each week.

Bywater's early impressions of Kirkby convinced him that a major disaster was inevitable:

'We seemed to do everything NOT according to the book, but we did start producing fuzes, and contrary to other assertions it has always been my belief that we were the first group to employ explosive workers and commence production … I might relate here an amusing talk I had with Bill Lang one lunch time well before February 1944. Bill was trying to impress me with how he had improved production output in 3C19 and asked me to walk through the building with him after lunch. My reply jokingly was that I would rather walk around the outside of the building than the inside … '

Accidents were part of the course:

'One other story, or tragedy that comes to mind, concerns the filling of time fuzes for 3.7 inch Anti-Aircraft shells. We were asked to get these into production urgently and as the layout was hastened we had not received guards for the drills which were used in the filling operations on the time rings, the row of drilling machines were shaft driven with safety stop handles at strategic points. As the female operatives were compelled to cover their hair (woollen hats were provided) I agreed to carry on without the guards until they arrived. One morning on arriving at my office on fuze group I was horrified to find on my desk a great mop of hair in a woollen hat. Apparently the female operator had allowed a fringe of her hair to be outside the hat (a not uncommon practice despite the ruling), and her hair had become entangled in the drill. Bill Port the Assistant Foreman quickly pulled the emergency stop but not before the hair had become tightly wound around the drill right up to the woman's scalp. Deciding to free the woman Bill Port lopped off her hair with a large pair of scissors and freed her. She subsequently sued the factory and was awarded £650 if I remember correctly. I did not get any Brownie points and production ceased until the shields were received … ' (ibid).

George Cross

But Bywater certainly did win Brownie points - and the George Cross - for his supreme gallantry when disaster finally struck on 22 February 1944. He sets the scene:

'I hurried up to the Danger Area gate where I deposited my large supply of smoking materials and hurried down to the Men's Change Room on Group 3, donned cleanway goloshes and headed onto the Group. Only a few yards from the change room was someone's oesophagus lying on the cleanway. I asked Bill Port to remove it and proceeded to 3C19. The roof had been blown away (designed to do just that) and one of the main brick walls was swaying in the breeze … ' (ibid).

For the purposes of an overall summary of events, no better source may be quoted than Bywater's obituary notice in The Daily Telegraph, 8 April 2005:

'On February 22 1944, in one of the buildings of the Royal Ordnance Factory at Kirby, in Lancashire, 19 operatives, most of them women, were at work on the last stage of filling anti-tank mine fuzes. Each operative was working on a tray of 25 fuzes, and in the building at the time there were some 12,000 stacked on portable tables, each holding 40 trays, or 1,000 fuzes.

At 8.30 a.m. that morning, one fuze exploded, immediately detonating the whole tray. The girl working on that tray was killed outright and her body disintegrated; two girls standing behind her were partly shielded from the blast by her body, but both were seriously injured, one fatally. The factory was badly damaged: the roof was blown off, electric fittings were dangling precariously; and one of the walls was swaying in the breeze.

The superintendent arrived with Bywater, his factory development officer. It seemed quite likely that the damaged fuzes, and others which could be faulty, might cause an even larger explosion. The high wind at the time, or any vibration, could set off further detonations over an area of half a mile.

Bywater cleared the building so that the maintenance crew could shore up the walls. He then volunteered to take on the dangerous task of removing all the fuzes to a place of safety where they could be dealt with.

Having selected some volunteers, he started at once. Bywater and his colleagues worked for three days moving the fuzes to a position close to the exit and then transporting them to a site about a mile away, where they were destroyed. By the end they had removed 12,724 fuzes from the factory.

Bywater gave instructions that he was to be given any fuzes that looked defective, and 23 were passed to him. On each occasion, he made his colleagues take cover while he removed the fuze and put it into a tray well away from the others. He then placed the tray on a rubber-tyred flat trolley and, with one colleague carrying a red flag 50 yards ahead, and another 50 yards behind, he slowly pushed the trolley to the destroying grounds.

There he personally laid out the fuzes in specially prepared pits. He placed sandbags on each of the pits and connected the electrical detonator and gun cotton primer. Not until he was certain that the operation had been made as safe as possible did he delegate to his colleagues the task of destruction, which went on for seven days a week for a month.

One fuze, Bywater judged, was in such a sensitive condition that it was too dangerous to be carried to the destruction site. He knew of two instances in which men trying to handle such a fuze had been blown to pieces. But to destroy the fuze inside the factory would cause enormous damage.

Selecting a location a short distance from the building, Bywater had an iron safe placed there with plenty of sandbags around it. Then, having sent all his colleagues out of the danger area, he carefully picked up the fuze, tip-toed across the grass and gently placed it in the safe. The sandbags were piled on, everyone withdrew out of range and the fuse was detonated.

In the investigation that followed, it was discovered that the original explosion at the factory had been accidental, caused by a defective striker. A faulty design in the stamping machine which marked the fuze heads with the lot numbers and dates of filling had damaged the striker stems.'

In his unpublished account of his wartime experiences, Bywater describes how he encountered no less than 23 fuzes of a 'sensitive nature' and how he dealt with some of them. On one occasion, he enlisted the help of a colleague:

'The idea was to lay a demolition explosive charge against the fuze body and hold it firmly in place with a couple of sandbags - this was the ticklish part - if the sandbags moved they could well cause the complete rupture of the striker head.

I lay down stretched out flat on my stomach and held the fuze firmly whilst Mark placed the demolition charge against it. He then produced the sandbags. The first one he put in place moved slightly as he released his hold, and I held my breath. He was a little more careful with the second, and we decided everything was OK. We walked back to the Air Raid Shelter, where we had the Firing Equipment and, shortly, there was no more worry with that fuze.'

Bywater was invested with his G.C. by King George VI at Buckingham Palace on 24 October 1944.

Here we go again - G.M.

Bywater's takes up the story:

'It was some little time before we twigged that even if the fuze complied with the empty specification, if all the tolerances on all the many parts were taken to their respective limits, the fuze could arm by being dropped a few inches even with the safety pin in place. In that eventuality the fuze could then detonate at any time, within a six-hour time span. Naturally I forwarded a memo to the Superintendent advising him of the position and recommended that the fuzes not be filled. The outcome was fairly speedy. Because of the importance to the war effort the fuzes had to be filled, I understand that the edict was signed by Sir Stafford Cripps himself. At Kirkby all went well until 5C38 met with disaster and the details are now pretty well known' (ibid).

As recounted above in the relevant London Gazette entry, the disaster at 5C38 occurred on a dark, rainy night during the filling of ammunition, and the initial blast was followed by others which put out all the lights: the only illumination on the site was provided by the numerous fires.

Once again, Bywater volunteered to clear the wrecked building, a task undertaken with a mass of anti-personnel, anti-disturbance and time-delay bombs scattered about the complex: all were in danger of detonating without warning. Such was the magnitude of the task in hand that it took three months to be completed. Luckily he managed to maintain his sense of humour:

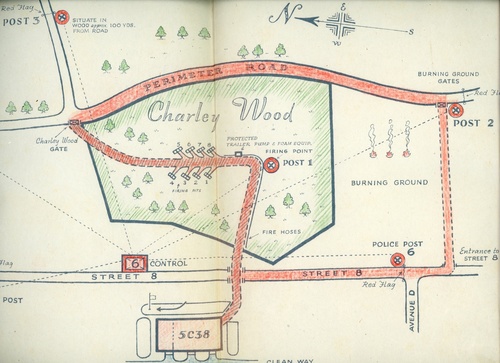

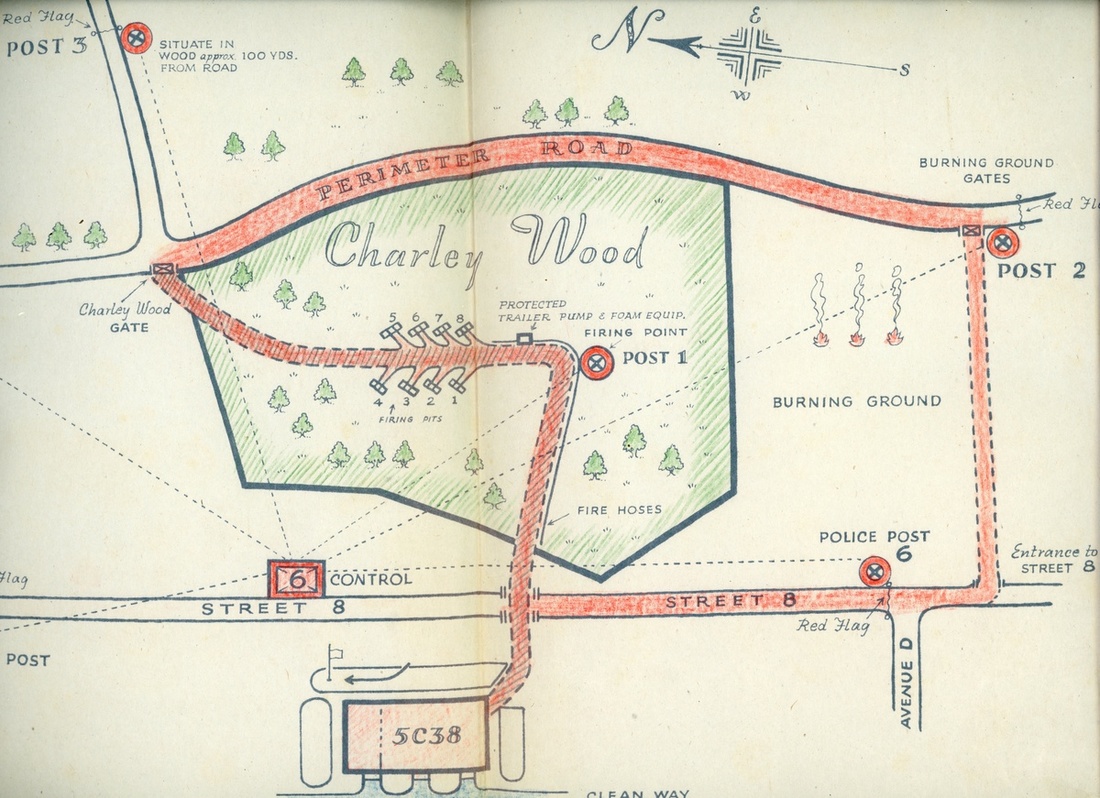

'We did have some hilarious moments even in most gruesome circumstances during the initial clean-up operation. In those first few days we were trying to clear an entrance way into the building, treading warily but not meeting much in the explosives field. We encountered mainly smashed furniture, smashed equipment and plenty of human remains. After a day or two the smell became pretty intolerable, James Murdoch and Bill Panton seeming to be affected. James asked for a mask which did not satisfy him so I suggested a little drop of Dettol in cotton wool inserted in the mask might help. I thought he should understand that it should be diluted. Not only did he use it neat but obviously soaked the cotton wool in it. Result, a ruddy blistered face … I think we chose to laugh at anything no matter how serious it might be. The three months the clearing of 5C38 took really began to drag. The frequent delays due to repairs to the road into Charley Wood - repairs to the tanks - mainly the tracks, repairs to detonating pits, etc. It was a relief from boredom when the site was eventually cleared a few days before Christmas' (ibid)

Bywater and nine of his fellow workers were awarded George Medal (G.M.).; two others received the B.E.M.

On receiving his G.M. from H.M. The King at Buckingham Palace on 6 November 1945, Bywater became the only civilian to hold both the G.C. and G.M.: that unique record stands to this day.

Post-war

At the war's end he became works manager at R.N. & Coate & Co., the cider makers, at Nailsea, Bristol and, in 1947, he married Patricia Ferneyhough. Emigrating to Australia in 1953, he set up an ordnance factory but later joined the Reserve Bank of Australia as a General Manager of the note-printing branch.

On retiring in 1976, he and his wife bought a farm on the banks of the Murray River but they later moved to Scone in New South Wales. Bywater died there on 5 April 2005, aged 91, and is buried in the Scone Lawn Cemetery.

Sold with a copy of Bywater's unpublished account of his wartime experiences, together with a comprehensive album of original letters and newspaper cuttings, offering congratulations on the awards of the George Cross and George Medal, and a superb archive of contemporary information regarding the events leading to both awards:

(i)

Letter of notification from Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, Minister of Supply and M.P. for City of London, informing Bywater of the award of the George Cross, dated 25 September 1944; a second letter of notification from John Wilmot, Minister of Supply and M.P. for Deptford, informing him of the award of the George Medal, dated 17 September 1945, both addressed to 1 River View, Waterloo, Liverpool, 22.

(ii)

Certificate from the Royal Society of St. George, electing to Honorary Membership of the Society 'Richard A. S. Bywater, M.Sc., A.R.I.C., upon whom His Majesty the King has been graciously pleased to confer the George Cross', 8 November 1944.

(iii)

A letter of congratulations on the award of the George Cross from Mr. C. S. Robinson, Director General of Filling Factories, dated 25 September 1944:

Shell Mex House

London W.C.2

Dear Mr. Bywater,

I have learned with the very greatest pleasure that H.M. the King has bestowed upon you the George Cross, and, as Director-General of the Filling Factory Department, I should like to be among the first to congratulate you upon this very high Honour.

Together with Lt. Col. R. A. Thomas, H.M. Chief Inspector of Explosives, and your Superintendent, I spent some time in the wrecked Building, shortly after the explosion, and was, therefore, in a position to realise the extremely risky and lengthy task confronting anyone charged with the responsibility of removing and destroying several thousand fuzes - all in uncertain condition and some in a quite clearly dangerous state.

The responsibility was undertaken by you as Leader of a team of brave men, upon whom I am glad to know His Majesty the King has also bestowed Honours.

The Filling Factory Department shares with R.O.F. Kirkby the pride and pleasure in the award of our first George Cross.

With kind regards,

Yours sincerely,

C. S. Robinson,

DIRECTOR-GENERAL: FILLING FACTORIES.

(iv)

Further letters of congratulation upon the award of the George Cross from A. R. V. Steele, Director of Filling Factories; Dr. C. W. Hart-Jones, Deputy Director of Filling Factories; Lt. Colonel G. Kellett, Deputy Chief Inspector of Armaments; Dr. C. N. Swanson, Assistant Chief Medical Officer, Ministry of Supply; B. A. Weston, Regional Development Officer, Lancashire Filling Factories; A. Roberts, Assistant Manager, Group 5, R.O.F. Kirkby; R. Parker & H. C. J. Innocent, Shop Mangers, R.O.F. Kirkby; Mr Charles Gumner, President of the R.O.F. Association of Professional Staff, and J. E. Cleverly, Secretary of the Risley Branch, Lancashire; Alexander Findlay, President of the Royal Institute of Chemistry; T. W. Jones, Editor of The Industrial Chemist; G. S. Mountfield, Landlord of 1, River View; W. H. Reynolds, Headmaster, King's Norton Grammar School for Boys, Birmingham; Mr. E. P. Beale, Pro-Chancellor, University of Birmingham; and Miss B. Foyle, Director of Boxfoldia Ltd.

(v)

A charming letter in pencil written by a very young David Bywater, the recipient's nephew, dated 28 September 1944:

'Dear Uncle Arthur,

I am very glad you have won the G.C. Mother, Daddy and I were very exsited. How did you take the fuzes out of the bombs? I wish you had told me when I was on my holerday. Are you having nise wether? I have lernd too swim this week. I have been in four times.

Love David.'

(vi)

Telegrams offering congratulations upon the award of the George Cross from Graham Satow, Past Regional Director, Filling Factories; R. N. Coate, Managing Director of R. N. Coate & Co. Ltd; Grace Gordon & John Beasley and Bernard Bywater.

(vii)

Formal letter from the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, St. James's Palace, S.W.1., inviting 'Richard A. S. Bywater, Esq., G.C.', to an Investiture at Buckingham Palace on Tuesday, 24 October 1944.

(viii)

Letters of congratulations upon the award of the George Medal from H. J. T. Ellingham, Secretary of the Royal Institute of Chemistry (2).

(ix)

Together with over 40 contemporary newspaper cuttings, offering details of the events leading to both awards. One of them, written by the 'Express Staff Reporter', Liverpool, states:

'G.C. Moved Buried Explosive

Two-shift workers leaving and entering the canteen at the first meal break at a north-west R.O. factory tomorrow will toast Mr Bywater, 30-year-old chemist, who risked his life to avert an explosion while they were working.

With the walls threatening to collapse, he organised the removal of 12,000 fuses - between 2,000 and 3,000 pounds of sensitive and powerful explosive - that might have blown up with a careless footstep - from a building that had been damaged by an explosion that killed two women workers.

That was in February. And tonight it is announced that Mr. Bywater - Mr. Richard Arthur Samuel Bywater, factory development officer, a young married man with a 20 months-old baby son, of River View, Great Crosby, Liverpool - gets the George Cross.

He went in through the smoke and dust to reach stacks of fuzes covered with wreckage. Roof beams were lying across them. A high wind threatened to blow down the walls.

He picked five men - "five men I knew were steady, careful and good at their jobs," he said tonight - and outlined the situation to them.

"One slip might be the end," he warned.

"We had to be careful not to tread on any of the fuzes. A blow from a man's hand might have set one off. Many of them were hidden. We could not see what condition those were in, and, well, we just took a chance and pulled them out."

He went in first, felt his way carefully through the first pile of wreckage, lifted it out piece by piece. Then he picked up the fuzes and put them into a tray, rolled them out of the building on a rubber-tyred trolley.

For three days, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. he led his men into the room to continue the work. His small band of volunteers, most of them married men, some with children, were: James Shanks Murdoch, aged 40, shop manager, of Horn-lane, Liverpool; Mark Victor Rowling, aged 34, shop manager of Oxford-Road, Bootle; William James Panton, aged 32, foreman, of Lancaster-avenue, Liverpool. They get the B.E.M. Commendations go to William Lang, aged 36, shop manager, and William Ormerod Watson, aged 42, assistant foreman.'

A cutting from the Liverpool Daily Post, dated Wednesday 7 November 1945, offers further insights into the award of the George Medal:

'Explosion-Fire-Rain

"At four in the morning on September 15 there was a shattering explosion in one of the filling sheds," Mr. Gale told me, "and within a few seconds fires were blazing in the midst of the bombs. There were about twenty-four operatives in the shed at the time, and eight of them were killed outright by the blast. One man was pinned under a girder, unable to move. The tragic scene was aggravated by a heavy downpour of rain and the fact that under the fallen masonry of the roof, the floor was littered with explosive powder and bombs which could detonate at any moment."

Here Mr. Denny - who was in bed half a mile away when the explosion shook the village - took up the story:

"The bombs were exploding all around us for about an hour and a half while firemen tried to extinguish the flames and rescue men dragged the wounded away from the building," he said. "One of the fires was put out fairly quickly, and I ordered the building to be cleared. At daybreak, a more serious fire started which, if not quickly controlled, could have endangered the whole factory."

By mid-morning of the 11th all the fires had been extinguished, but more than seventy 'clusters' each containing fifty-six bombs, lay around under the debris. If they exploded, Kirkby and the surrounding countryside might have been blown up.

Superintendent Gale devised a scheme for disposing of the bombs. Some were blown up at the wrecked site at five-hour intervals, others were dragged by rope and detonated in the woods near the factory, but there were still hundreds which were too delicate to be touched.

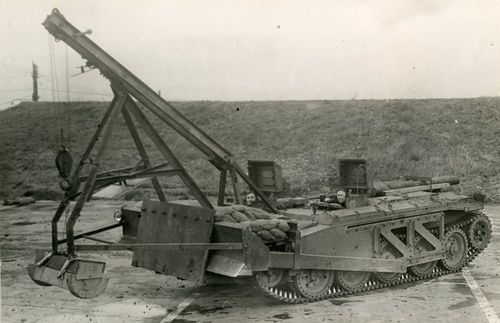

For the following three weeks, bombs were blown up in a most ingenious manner. A tank was borrowed from the Army and fitted with a bull-dozer front and extra steel plating with sandbags to give extra protection.

Mr. Louis Fitzmaurice, M.B.E., the chief technical assistant, Mr. R. T. Edwards, of Thomas Bates, Ltd., and Mr. R. A. S. Bywater, G.C., the Kirkby development officer, volunteered to drive the tank.

Special pits were dug near the wrecked building and the tank scooped up bombs from the debris and dropped them into the pits where they were blown up. The tank was sealed and the men inside were unable to see. By January, 1945, all the clearance work had been completed and the factory was pronounced "out of danger." '

(x)

A formal typed report, approx. 600 words, to Assistant Superintendent Mr. W. E. Denny, by Bywater, regarding the clearing of 3. C. 19, 22-24 February 1944, and dated 26 February 1944. This report highlights the severity of the scene and the individual incidents which had to be dealt with:

'At 4.45 p.m., Mr. Lang informed me by 'phone that they had a dangerous fuze, with split striker, which they had removed from 3.C.15., and had locked in an iron safe outside 3.C.18. I told them to see that a suitable area surrounding the safe was roped off. On Wednesday morning, 23.2.44., I recommended the immediate destruction in situ of this fuze, and, after seeing the fuze, you agreed. The Electric and Steam supplies were isolated, the iron safe was suitably sandbagged to direct the blast, and the fuze was destroyed by electric detonator, and guncotton primer in your presence, at 11. a.m.

By 12.00 noon, the areas containing the remains of Miss Landry, the operative killed by the detonation, had been cleared of debris and fuzes, and A.F., Mr. Port and Foreman Mr. Wood, were called to remove the remains of Miss Landry.

In all, 12,724 fuzes were removed from the building.'

(xi)

A Second formal report submitted to D.G.F.F. on the Clearing of (the) Site of Explosion at Kirkby During the Latter Part of 1944; 28 typed pages, handback bound, containing a wealth of information regarding the George Medal event, notably the clearance on bombs and clusters from the site and the logistical difficulties associated with the site, typically partially demolished buildings, poor weather and personnel entering exclusion areas; containing 7 original photographs of damage done to the building, taken from different viewpoints; 10 photographs showing draw lines and lead indicators to the pits in Charley Wood; 7 photographs showing badly damaged and burnt-out clusters; 6 photographs showing tank operations, explosion in the pit and further badly damaged clusters, and 4 further original photographs showing primed explosive and the floor of the building once fully cleared.

(xii)

One portrait photograph and ten group press photographs, the majority dated to reverse 1944 and 1945, of Bywater and decorated men associated with the two incidents.

(xiii)

Original Third Supplement to The London Gazette, dated 22 September 1944, detailing the award of the George Cross; together with corresponding Supplement for the George Medal, dated 14 September 1945.

(xiv)

A request letter from Debrett's, asking Bywater to offer particulars so as to be included in the 1945 Edition.

(xv)

A signed menu booklet for the Fifth Reunion Dinner of the V.C. and G.C. Association, held at the Café Royal, London, 14 July 1966, with the signatures of multiple V.C. and G.C. winners, inclusive of Odette S. Hallowes, G.C., M.B.E, Richard Annand, V.C., Rambahadur Limbu, V.C., M.V.O., and a number of politicians and dignitaries, including Sir Anthony Eden. Approx. 30 ink signatures; together with two limited edition cover-slips showing portrait photographs of Bywater, both signed by him in ink.

(xvi)

1977 E.II.R. Silver Jubilee Medal Certificate to 'Richard A. S. Bywater, G.C., G.M.'

Reference sources:

Ashcroft, Michael, George Cross Heroes (Headline Review, 2010).

Bancroft, Jim, Local Heroes (1992).

Bywater, Richard, G.C., G.M., his unpublished wartime memoirs; together with sources from the above described archive.

Hebblethwaite, Marion, One Step Further - Those Whose Gallantry Was Rewarded with the George Cross (Chameleon HH Publishing, 2006).

The Victoria Cross and The George Cross - The Complete History; Vol. III (The V.C. and G.C. Association; Methuen, 2013).

Subject to 5% tax on Hammer Price in addition to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Estimate

£100,000 to £120,000

Sale 18001 Notices

Print catalogue erroneously lists this item as lot 579