Auction: 17002 - Orders, Decorations and Medals

Lot: 393

'Suddenly, with no warning at all, our peace was shattered by a series of deafening crashes, which developed immediately into a loud roar. The plane rocked and pitched forward, and I felt the stick go dead in my hands.

'Christ, it's happened,' I thought, 'but it just can't be, it can't possibly happen to us.'

Long training came to my aid, and although I felt like jelly inside, I tried to keep my voice quiet, as I came out with the formula, "Prepare to abandon aircraft."

Not a sound from the intercom.

The cockpit was glowing bright yellow, as the starboard wing had caught fire.

I knew a night fighter had scored a direct hit on us, as I had seen a yellow stream of tracer spreading fanwise in front of us, and below.

The roar of flames increased, and although I knew it was useless, I cut the starboard engines, and pressed the extinguishers.

The Perspex around me was shattered, and a hurricane was sweeping the cockpit.

"Jump everybody," I yelled, but felt that the intercom was dead.

V-Victor was going down very steeply, and I could see the altimeter unwinding fast, and started to panic.

At that moment another loud bang, and more tracer appeared ahead … '

Squadron Leader John Hartnell-Beavis describes in Final Flight the moment his Halifax was downed over Holland in July 1943: he - and his Wireless Operator 'Smithy' Smith - were the only two members of crew to survive the incident.

An outstanding Second World War evader's D.F.C. group of five awarded to Flight Lieutenant R. A. 'Smithy' Smith, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, who completed 26 operational sorties in Halifaxes of No. 10 and No. 76 Squadrons, prior to taking to his parachute over Holland after his aircraft was downed by a night fighter on returning from a strike on Essen on the night of 25-26 July 1943

Having then spent nearly three months in a string of Dutch resistance 'safe houses', he and a fellow evader undertook a perilous journey to freedom via Occupied France and Spain: 'The first stage of their journey, from Amsterdam to Paris, was spent crouching amid dynamos in the floor of an electric train. In the French capital they again changed identity - and had time for a casual stroll down the Champs Elysee and a visit to a night club, under the Germans noses … '

After further hair-raising adventures - his fellow evader was compelled to deck an over inquisitive Spaniard - both men reached Gibraltar on 27 October 1943: just three weeks earlier Smith's wife had been informed by the Air Ministry that an International Red Cross report suggested he had been killed in action

Distinguished Flying Cross, G.VI.R., the reverse officially dated '1944', with its Royal Mint case of issue; 1939-45 Star; Air Crew Europe Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45, good very fine (5)

D.F.C. London Gazette 7 January 1944.

Raymond Arthur 'Smithy' Smith was born in Leicester on 9 February 1921. A talented skater, he was employed as a machine tool operator prior to his enlistment in the Royal Air Force in December 1940.

76 Squadron: Bomb Aimer's leg amputated

Having then qualified as a Wireless Operator, he attended No. 20 Operational Training Unit at R.A.F. Lossiemouth and was posted to No. 76 Squadron, a Halifax unit operating out of Linton-on-Ouse, in February 1943: his C.O. was Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire, D.S.O., D.F.C.

Smith teamed-up with Squadron Leader John Hartnell-Beavis's crew, his subsequent operational career being described in vivid detail in the latter's wartime memoir, Final Flight. Following raids on Cologne and Nuremburg soon after their arrival at Linton-on-Ouse in early 1943, pilot and crew were ordered to St. Nazaire, normally considered a 'cushy number'. But as recounted in Final Flight, it was to prove quite the contrary:

'On our way out to St. Nazaire, with about 50 miles to go, we could see flak exploding like glittering fireworks at about our level, and my new engineer, who had been standing behind my seat, started to get extremely agitated and shouted down the intercom: "We can't go in that skipper, it's absolute murder." I told him to shut up but he carried on shouting down the intercom, getting more and more excited and begging me to turn back, and was obviously upsetting the rest of the crew. I called up the navigator and mid-upper gunner to get hold of him and keep him quiet, which they did by taking off his oxygen mask and intercom mike, and we carried on to line up for the bombing run …'

Having been read the riot act on his return to base, the nervous Flight Engineer promised it would never happen again. Hartnell-Beavis continues:

'I felt rather sorry for my engineer when three days later we were sent to Hamburg, together with about 800 other aircraft, on a very heavy raid. The flak over Hamburg was always particularly dense, and I had instructed the rest of the crew to take extreme measures to control him should he go to pieces again. In the event, even though the flak was as thick as ever, he behaved perfectly and kept very quiet, not even joining in the usual babble of conversation on leaving the target area.

My engineer told me later that he was absolutely terrified on the first few raids and it took him about six trips to get used to seeing the flak and fireworks. I felt very sorry for him, but glad that I did not have to report him for 'Lack of Moral Fibre', as this was usually a Court Martial offence.'

As it transpired, the Flight Engineer's new found courage proved timely, for the remainder of the crew's operational career was to witness a spate of trips to Germany's most heavily defended targets, Berlin among them, in addition to no less than five trips to Essen.

In a raid on Kiel on the night of 4-5 March 1943, their Halifax was hit by an incendiary bomb from above. Final Flight takes up the story:

'On 4 April, we flew from Linton to Kiel, our eleventh operation, and whilst flying over the target area at about 19,000 feet, we were hit by a bomb from above, obviously from a Lancaster, and this dropped through the nose of the aircraft and amputed my bomb aimer's left leg below the knee, while he was lying at the bomb sight giving instructions on the run up to the target. We gathered later that this was a small incendiary bomb.

The large hole in the nose left a hurricane blowing through the aircraft, and we used up nearly all our fuel on the return trip, to get back as quickly as possible. He was obviously in a lot of pain and moaning down the intercom, and I got my navigator and W./Op. [Smith] to carry him to the bed in the rear of the aircraft and give him a shot of morphia. We always carried a first aid kit, which had about a dozen ampoules of morphia, and you would stick the needle into the patient's arm and leave it there. I was in touch with the W./Op. through the intercom, who said that the first shot did not seem to help him much, so I told him to give another. He was losing a lot of blood although his thick flying suit did help to staunch the flow, and my W./Op. told me he was still in a lot of pain so remembering my time at Colingdale Hospital in the early days of continual pain, I told him to give him a third shot even though I felt this might be dangerous, but we thought he would probably die in any case before we got home.

On the way home, I called up the tower and told them to have the ambulance waiting and managed to pull off a very smooth landing. They took him off and operated straight away, amputating his leg just above the knee and within six weeks he was out and about on crutches and used to come and see us off on future operations.'

In early July 1943, and having transferred with Hartnell-Beavis's crew to No. 10 Squadron, another Halifax unit, operating out of R.A.F. Melbourne, Yorkshire, Smith was commissioned Pilot Officer.

Musical interlude

'I found that night bombing trips really suited my temperament, particularly on clear nights, flying at about 19,000 or 20,000 feet well above the clouds, the tops of which were illuminated by the moon, trimming the aircraft to fly dead straight and level, and setting the Sperry gyro. So as to fly hands and feet off. We would drone on for hour after hour, listening to Ivy Benson and her all Girls Band which was one of our favourite orchestras at the time, which 'Smithy', my W./Op. would tune in to, and connect to the intercom. Vera Lynn was another of our favourites. You could carefully adjust the throttles so that the engines were all perfectly synchronized, and with the aircraft as steady as a rock, you could well have been sitting in an armchair on the ground …' (Final Flight, refers).

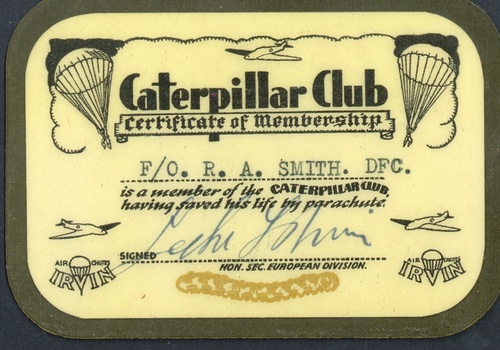

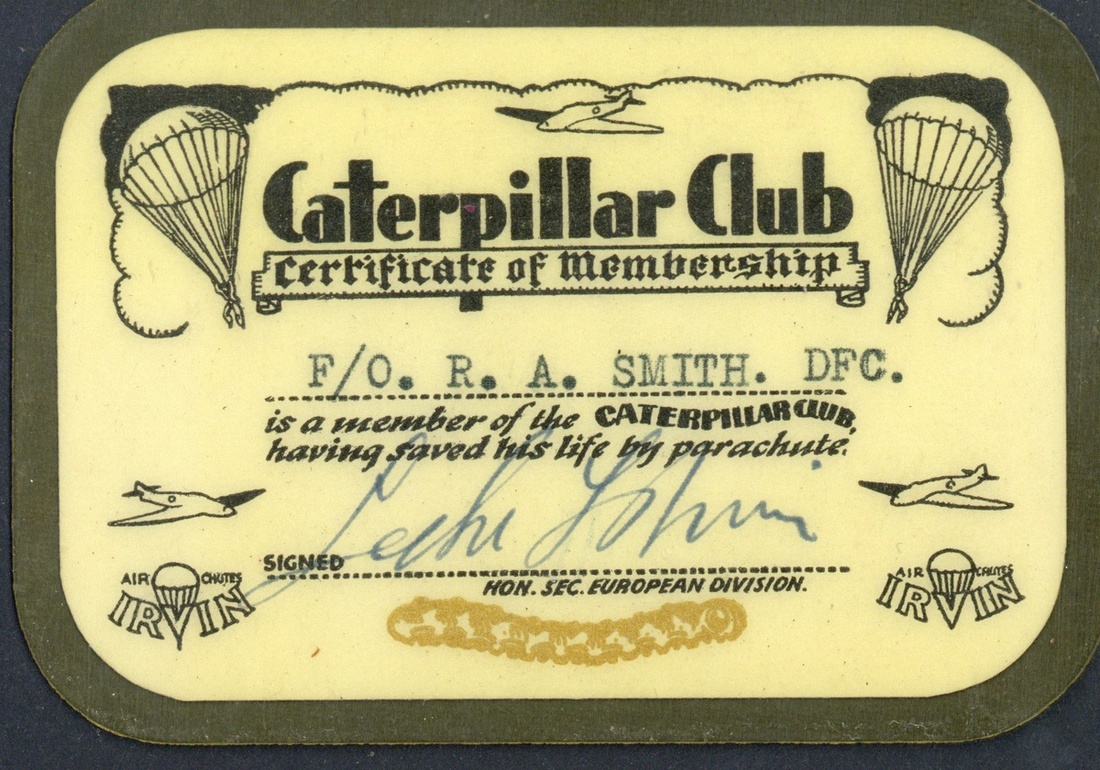

Caterpillar and R.A.F. Escaper's Clubs:

First up at 10 Squadron was a strike on Duisberg and, two nights later, 'we went back to the Ruhr to bomb Bochum, and on this trip we were coned by searchlights for six minutes and came back with a number of holes in the fuselage.'

And so to events on the night of 25-26 July 1943, when Smith and his crew were ordered to attack Essen. As stated, their Halifax was seriously damaged by enemy night fighters on the return trip and, at 0130 hours, Hartnell-Beavis gave the order to abandon the stricken aircraft: he and Smith managed to get out via the forward escape hatch but the remainder of the crew perished, including the Navigator, whose parachute appears to have failed to open.

Hartnell-Beavis became a P.O.W. but Smith remained at large. In his subsequent M.I. 9 debrief, he described at length his subsequent journey to freedom, a journey made possible by the gallant assistance of members of the Luitse family: one of them, Simon Karel Luitse, was subsequently arrested by the Germans and died in captivity in April 1945.

Having landed in a wood and buried his parachute, Smith was fortunate to meet a member of the Luitse family the following day. Given civilian clothing, he was taken to a farm near Oisterwijk, Brabant, and thence to Rotterdam.

Subsequently sheltered at a string of 'safe houses' in the period 26 July to 9 October 1943, he commenced his journey to Occupied France via Amsterdam on the latter date. Here, then, in the company of another evader, Sergeant Hempstead, the commencement of an uncomfortable rail journey 'crouching amid dynamos in the floor of an electric train'. Having then taken in the local sights at Paris - and attended a night club - the airmen were issued with new false papers and continued their journey to Bordeaux and Bayonne. It was at the latter place that Smith hid underneath another train bound for Irun. He takes up the story in his M.I. 9 debrief:

'I lay flat on a brake bar and clung with my hands and feet on to the cross girders. I found it very difficult to hang on, as, when the train was in motion, the brake bar moved. The train got into Hendaye, France, about two and a half hours late. My helper got off here and came back saying that some of the carriages were to be dropped and that we would have to move further up the train. We scrambled out, ran up the track and again got underneath another carriage. I took a pep tablet here.

Our train was considerably overdue when it reached Irun and we found the Lisbon train, which we had intended to catch, had already gone. We therefore made a dash for the goods yard and sat on the ground underneath a stationary goods train. We waited all day under the train. By this time we were very hungry as we had had nothing to eat since we left Dax. At night the train we were under began to move and we had to scramble out very quickly in order to avoid being pinned under.

We moved to another goods train and sat up on the girders. After a short time a man came along tapping the wheels. My helper lost his balance and slipped off. Realising we should probably all be found, we made a dash. We got separated but a little later I found Hempstead again … '

It would appear the wheel-tapper was the Spaniard decked by Smith's comrade. Be that as it may, the pair of them remained undetected until boarding a train for San Sebastian the following day, where, at length, they reached the British Consulate. Taken by car to Madrid, they commenced their final journey - to Gibraltar and freedom - on 24 October.

Smith was awarded the D.F.C.

Postscript

Following his successful 'home run', he transferred to Transport Command as a W./T instructor on ground duties and remained similarly employed until demobilised at war's end. He was advanced to Flight Lieutenant in January 1944.

In January 1951, Smith re-enlisted in the R.A.F. and trained as a signaller at Dishforth, but he was discharged as physically unfit in the following year after being seriously injured in a motor-cycle accident.

He was for many years the publican of The Crown at Gilmorton, near Rugby, Warwickshire, and died in March 1997.

Sold with a quantity of original documentation and related artefacts, including:

(i)

The recipient's R.A.F. Observer's and Air Gunner's Flying Log Book (Form 1767 type), covering the period September 1944 to March 1951, the inside front cover endorsed: 'Original Log Book lost at R.A.F. Station Melbourne, Yorks. Approx. Hrs. 350.'

(ii)

His Buckingham Palace D.F.C. forwarding letter.

(iii)

His wartime R.A.F. Service and Release Book, and post-war R.A.F. Certificate of Service.

(iv)

A confidential wartime assessment / report, with portrait photograph.

(v)

His Caterpillar Club and R.A.F. Escaper's Society membership cards, together with blazer patch for the latter.

(vi)

Air Ministry letter addressed to his wife, dated 7 October 1943, in which it is concluded - as a consequence of a recent International Red Cross report - that he is likely to have lost his life: happily, in fact, he was on his way to Gibraltar.

(vii)

A quantity of photographs, including a dozen or so of the wartime era, together with quantity of newspaper cuttings.

(viii)

National Skating Association (G.B.), prize medals (4), comprising 1st Place in the Three Miles Inter Club Relay Roller Skating Championship of Great Britain, 1939, silver and enamel; 1st Place in the Speed Test, gold and enamel; 3rd Place in the Speed Test, bronze and enamel; and Winner's Medal for the Midland Counties Speed Skating Championship, 1938, gold, the reverse named 'Raymond A. Smith', in its fitted box of issue.

(ix)

A presentation wrist watch, the reverse inscribed 'Presented to P./O. R. A. Smith by F. Pollard & Co. Ltd. in recognition of being awarded the D.F.C., Jan. 7 1944.'

Additional reference sources:

Hartnell-Beavis, Squadron Leader J., Final Flight (Merlin Books Ltd., Braunton, 1985).

Subject to 20% VAT on Buyer’s Premium. For more information please view Terms and Conditions for Buyers.

Sold for

£2,300