Auction: 11011 - Orders, Decorations, Campaign Medals & Militaria

Lot: 4

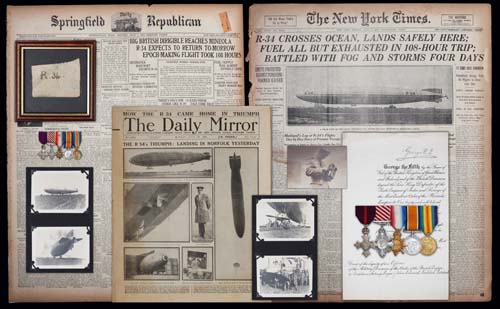

A Fine 1919 ´Paris Peace Conference´ Military Division O.B.E., and Rare Airship Pilot´s A.F.C. Group of Five to Major J.E.M. Pritchard, Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force, An Authority on Airships, He Was Admiralty Observer, and Photographer in R34 For One of the Great Feats of British Aviation - The First Return Atlantic Crossing By Air, July 1919. He Also Made History When He Parachuted Down From R34, Thus Making the First Airborne Landing on US Soil By A Foreigner. Pritchard Was Tragically Killed in the R38 Disaster, ´When She Suddenly Buckled, Went Into a Slow Nose Dive and Then Broke Into Three Pieces, Spilling Men, Parts and Debris Into the River Humber´, 24.8.1921 a) The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, 1st type, Military Division, Officer´s (O.B.E.) breast Badge, silver-gilt (Hallmarks for 1919) b) Air Force Cross, G.V.R., unnamed as issued c) 1914-15 Star (Ft. S. Lt. J.E.M. Pritchard. R.N.A.S.) d) British War and Victory Medals (Flt. Cr. J.E.M. Pritchard. R.N.A.S), generally very fine or better, with the following related items and documents: - The recipient´s miniature awards -Cases of issue for the O.B.E. and A.F.C. - Piece of the ´cloth´ frame of R34, in a small glazed wooden frame - Bestowal Document for the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Military Division, O.B.E., dated 3.6.1919 - A small number of original photographs of the R34 taken from the ground at different angles - Original copies of The Daily Mirror, dated 14.7.1919; The New York Times, dated 7.7.1919; and the Springfield Republican, dated 7.7.1919, all headlining the story of the flight of R34; and The Day, dated 24.8.1921, and The New York Times, headlining the crash of the R38 - Five extremely comprehensive files of research, replete with copies of articles, letters and reports relating to the recipient and the R34 and R38, and several photographic images of the recipient (lot) Estimate £ 4,000-6,000 O.B.E. London Gazette 3.6.1919 Capt. (A./Maj.) John Edward Maddock Pritchard A.F.C. London Gazette 22.12.1919 Flight Lieutenant (A./Squadron Leader) John Edward Maddock Pritchard, O.B.E. ´In recognition of distinguished services rendered during the War and since the close of hostilities.´ Major Edward Maddock Pritchard, O.B.E., A.F.C., born Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, 1889; his father was of Welsh origin, but was born in the United States, and fought during the Civil War; educated at Trinity College, Cambridge and the Royal School of Mines; made a Fellow of the Geological Society; commissioned Flight Sub Lieutenant, Royal Naval Air Service, 24.5.1915; graduated in practical ballooning and as an Airship Pilot, 1915; service during the Great War as an Airship Pilot, mainly flying sea patrols, included at R.N.A.S. Airship Station Polegate, where he was in command of S.S. (blimp) 9, from September 1915 and at Mudros, Eastern Mediterranean, where he was in command of S.S. 3, from April 1916; Flight Lieutenant 31.12.1916; advancing to Flight Commander the following year he went on to command C.24 whilst based at East Fortune and P.6 at Howden; posted to Admiralty Airship Department, as a Rigid Acceptance Pilot for Technical Flying Duties, September 1917; over the following year and a half Pritchard compiled various reports on German Zeppelin activity from a constructional, operational and technical flying point of view obtained by personal inspection of German Rigid Airships brought down over France, questioning German Rigid Airship Prisoners (in conjunction with the Air Intelligence Department, at Rouen) and translating captured note-books and log-books; appointed Technical Airship Officer, Inter-Allied Armistice Commission to Germany, under Admiral Browning, December 1918; appointed Admiralty Airship Representative to the Peace Conference, Paris (awarded O.B.E.), January 1919; in early 1919 he became involved in what was to be the highpoint of his career and one of the great feats of British aviation. R34- The First Return Atlantic Crossing By Air The R-34, or ´Tiny´ as her crew nicknamed her, was the biggest rigid airship in the British Fleet; constructed by William Beardmore & Company in Inchinnan, Renfrewshire, Scotland, between 1918-1919, R34 made her maiden flight to her service base at East Fortune, East Lothian, 14.3.1919; from nose to tail she was 643 feet (almost three times the length of a Boeing 747 ´Jumbo´ jet) and 92 feet high; approximately £242,000 (at the time) had been invested in the production of her to enable Britain to leapfrog the rest of the world in the ´aviation race´; having carried out her first endurance flight of 56 hours over the Baltic, 17th-20th June, it was declared that the R34 would attempt to undertake not only the first East-to-West crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air, but also the first return Atlantic crossing by air; if the flight were to succeed this would also constitute the longest flight ever by any aircraft and the longest time an airship had spent in the air, ´flying an airship all the way across the Atlantic in the year 1919 was nothing to smile about. No one knew if it could be done... Aerial navigation was in its infancy. During the war one seasoned Zeppelin skipper who set out to bomb Edinburgh found himself being forced down in Norway.... an airship... was subject to downdraughts and updraughts as well as headwinds, following winds and cross winds. No one knew what perils lurked in the upper air above the Atlantic..... No one had the means to study the high atmosphere for the direction of speed of the winds... From the R34´s crew of 30 (31 in the event- including a stowaway) the trans-Atlantic flight required faith in the technology, patience, a high degree of skill and a talent for improvisation. Plus an ability to rough it on minimal rations in a chilly interior that reeked of petrol and vibrated ceaselessly to five unsynchronised aero engines. They had to try to snatch some sleep between four hour watches in narrow hammocks that were swaying between the girders. All this had to be suffered for days on end without even the comfort of a cigarette (most were smokers). And with the ever-present prospect that they might have to ´ditch´ in the Atlantic and hope (rather than expect) to be rescued´ (Flight of the Titan, The Story of the R34, by G. Rose, refers); Pritchard was a member of the crew of 30, which with the exception of the American Observer present, had been with the R34 since her maiden flight, ´The R34´s Captain, Major George Scott, had joined the RNAS at the outbreak of war in 1914, had skippered Britain´s first rigid airship and then commanded the (German built) non-rigid Parseval P4. Under Scott were his second officer, Captain Geoffrey Greenland, third officer Lieutenant Harold Luck, engineering officer Lieutenant John Shotter, navigating officer Major Gilbert Cooke, radio officer Lieutenant Ronald Durrant, and meteorological officer Lieutenant Guy Harris. Also on board were Brigadier-General Edward Maitland (observer for the Air Ministry), Major John Pritchard (observer for the Admiralty) and Lieutenant-Commander Zachery Lansdowne (observer for the U.S. Navy). Non-commissioned officers and other ranks comprised three coxswains, two wireless operators, eleven engineers (two for each engine and one specialising in petrol supply) and four riggers´ (Ibid); given that this was such a massive undertaking with far reaching public interest on both sides of the Atlantic Maitland was placed in charge of press and public relations, writing a day-by-day narrative of the journeys, and Pritchard was equipped with a camera (the only one allowed onboard) to record not only aspects of technical interest in furthering airship research but also in an effort to control and strategically release pictures for publicity purposes at a later date by the Air Ministry. Outward Bound The R34 took off from East Fortune in the early hours of 2.7.1919; along with supplies and fuel 112 pounds of mail and parcels were stowed aboard, including letters from King George V and the Prime Minister, for delivery to the President of the United States upon arrival; Maitland, who´s daily narrative survives, records Pritchard as taking part in the ´first watch´ in the control car for the start of the Atlantic journey; this is one of many occasions that Pritchard is recorded in Maitland´s log including being constantly active with his camera on the first day of the trip, ´passing over oil steamer going up the Clyde - the crew wave us a greeting. Sunrise over lowest point of Bute. Very big storm over mainland on port beam and very dirty looking weather ahead.... Major Pritchard begins to get active with the camera´; basic conditions, including the only means of cooking food being a plate welded to the engine exhaust pipe, were made worse by the arrival of poor weather on the second day of the journey, ´the rain is driving through the roof of the fore car in many places, and there is a thin film of water over the chart table. The wind is roaring to such an extent that we have to shout to make ourselves heard´; however, days 3-4 of the journey were to prove the most trying for all concerned - especially due to poor engine performance, increasingly worse weather and a rapidly diminishing supply of petrol; the latter gave particular cause for concern given that by day 3 they had used 75% of their petrol supply with well over a 1,000 miles still to go to reach their landing site on Long Island; however, as Maitland records, they all mucked in to help the skipper and his engineers, ´Having burnt a lot of petrol, the ship is so light, so Scott has to force her down on the elevators to get her into the cloud bank. We are now over a large ice-field - masses of broken ice floating on the surface in every direction. Take a turn with Pritchard of pumping petrol, which is a laborious and most unpleasant proceeding, and must be avoided in future ships´; by day four, having started with 5 engines the airship was down to 3, and it now encountered the worst weather of the trip going over the Bay of Fundy on the Atlantic coast of North America, ´she was to be battered by head winds, threatened by thunderstorms, sent reeling by bizarre shifts in air pressure and jolted by atmospheric electricity. It went on for most of the day and into the evening, forcing the crew into their parachutes and to hang on grimly to anything they could find... there were times that Saturday when they feared for their lives. More than once it looked as if the R34 would meet its end over the islands of the Western Atlantic...... What made the pitching and tossing of the R34 over the Bay of Fundy so alarming and dangerous was the fact that some of the engines were stopping and then flaring back to life in bursts of flame. The possibility of a spark igniting a slight leakage of hydrogen, and then the petrol, was always present´ (Flight of the Titan, The Story of the R34, G. Rosie, refers); however by a combination of luck, and sheer bloody mindedness the R34 arrived over its intended landing place (the Roosevelt Field, Mineola, Long Island) at approximately 9.30am on the morning of 6th July 1919, as the correspondent for The Times describes, ´With the band playing ´God Save the King´ and thousands of spectators standing bareheaded, the R34 dipped groundwards and dropped anchor at 10 o´clock this morning after a voyage which up to last night even experts feared might end in disaster´; however, there was still one more problem to resolve - when it had appeared that the airship may have to land elsewhere due to the shortage of petrol, ´the 12-man British advance crew who had been trained to usher the airship back to earth had made a dash from Washington to Boston to be ready... they were still in Massachusetts when Scott decided that he had enough fuel to see the R34 to New York. Which meant that the US Army troops at Mineola were left to secure the R34 without instruction´; this could not be left to chance and it was decided that someone from the crew would have to parachute down to show the soldiers how to land and secure the ship, ´Pritchard climbed out of his flying suit and into his best uniform, was helped out of one of the control car´s windows, and parachuted down from the R34 to make the first airborne landing on US soil by a foreigner. The New York Times described Pritchard´s jump as ´Parachute Brings First Air Pilgrim to American Soil´. The ´air pilgrim´ did his job, the American soldiers did theirs and at 09.54 (local time) the R34, trailing a Union flag and with a Lion Rampant of Scotland emblazoned on her nose, settled down onto Roosevelt Field. It was the triumphant conclusion of the first-ever east-west flight across the Atlantic and, at 108 hours 12 minutes, the longest any aircraft had been airborne. All the drinking water and most of the food had gone and there were only 140 gallons left in the R34´s petrol tanks, roughly enough for an hour´s flying. It had been touch and go, a very close run thing.´ (Flight of the Titan, The Story of the R34, G. Rosie, refers) Living the High Life Upon landing the crew were hit by a barrage of press and greeted by thousands of well-wishers; they received the following telegraph from the King, ´Your flight marks the beginning of an era in which the English-speaking peoples, already drawn together in war, will be more closely united in peace´; the wave of enthusiasm and general euphoria surrounding the flight continued for the next four days as the crew were treated like celebrities, with the officers being put up in the Ritz Carlton, and being wined and dined by the ´great and good´ culminating for some of them in meeting the President. Homeward Bound With extensive repairs carried out, supplies replenished and a larger store of petrol taken on board the R34 took off at 23.54 hours, 10th July, ´it was like something from another world. A huge stream-lined, silvery-blue shape caught in the crossbeams of powerful searchlights, prowling slowly over the Manhattan skyscrapers. In the early hours.... hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers rushed out onto the streets and rooftops and gaped up into the sky as the great ship, hundreds of feet long, rolled slowly across the city. Restaurants, hotels, theatres, nightclubs and bars emptied as people took to the street to gaze upwards. The sight was one of the greatest events of the summer of 1919´; thankfully for the crew the return trip was to be much less eventful, the only real controversy was that the landing site was moved by the Air Ministry at the last minute from East Fortune to Pulham, Norfolk; this was to be a great disappointment for the crew as their loved ones were not there to greet them upon their return; in fact it was speculated that the Air Ministry did this in an attempt to carefully control and stage the release of details of the flight to the press - the Air Ministry later came in for heavy criticism for not giving the R34 the welcome home it deserved; the ´Time of landing, 6.57am. Total time of return journey from Long Island, New York to Pulham, Norfolk, is therefore 75 hours and 3 minutes or 3 days, 3 hours and 3 minutes´ (Maitland´s log refers). R38 Disaster Pritchard was posted as Acceptance Pilot & Technical Flying duties, Airship Experimental & Research Division, Air Ministry, 22.10.1919; made an Associate Fellow, Royal Aeronautical Society, 1920, with whom he lectured upon Rigid Airships; as a Technical Expert he continued to work with Maitland and was employed as the airship trials officer for the R38, ´on a fine evening on Wednesday, 24.8.1921, thousands of people in Hull flocked to the banks of the Humber to watch the stately progress of Britain´s newest airship, the R38. Bigger and more advanced than the R34, the R38 had been built by the Royal Airship works at Cardington..... and was due to be sold to the US Navy. Manned by a crew of British and American airmen and a dozen or so engineers and observers, the R38 had completed two days of trials and was heading for the airship base at Howden, where she was to overnight before returning to Pulham in Norfolk. The airship had flown over Hull and was cruising at around 1,000 feet over the Humber when she suddenly buckled, went into a slow nose dive and then broke into three pieces, spilling men, parts and debris into the river. The horrified crowd watched as the ship was racked by two explosions that shattered windows all over the city. Then the R38´s hydrogen and petrol bloomed into flame and the burning remains settled on the Humber, where the spilled fuel generated a barrage of flames. The last wireless message received from the R38 was terse: ´Ship broken, falling.´ of the 51 men aboard the R38 only five survived..... Among the airmen killed that summer evening were three who had battled their way across the Atlantic in the R34´ (Flight of the Titan, The Story of the R34, G. Rosie, refers); two of those men were Maitland and Pritchard; the R38 had been designed with a structure that was too weak to withstand the pressures that would be placed upon its hull; something that Pritchard had highlighted in his reports on the test flights, protesting to the highest authorities, but to the cost of his life and many others, his protestations were ignored. Pritchard´s body was never recovered; he is commemorated on the Hull Western Cemetery Memorial.

Sold for

£16,000