The Collector’s Series, New York - Sale Results

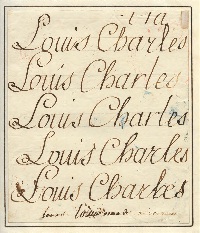

Every once in a good while, an autograph appears on the market that is so rare and unique that its presence in an auction becomes an event. Such was the case in Spink's Collectors Series sale held on November 16 in New York City, when we were able to offer the extremely rare autograph of Louis XVII of France and Navarre, known generally as Louis-Charles, the "Lost Dauphin." I have said that the item is rare and unique; I remember the first time I heard that phrase and wondered aloud whether it wasn't redundant to say that something unique is rare. In the world of collecting, that is not quite the case. Young Louis is the Holy Grail of French Revolution autographs because his writing is rare. The only examples known to be in private hands are a few leaves from a copy-book on which he has practiced writing his name in bold calligraphic letters. It was one of these rare leaves, covered with the Dauphin's name, "Louis Charles," that appeared in Spink's November sale. What made the autograph unique was the presence at the bottom of the page of three additional signatures as "Louis," each as part of a string of characters in the prince's natural handwriting undoubtedly scribbled in order to finish the ink in his pen, as each begins boldly and then fades as the ink runs out. Thus, the item was both rare and unique, making it especially desirable as the only one of its kind among a type that is already very scarce. Accordingly, the autograph brought a strong $30,000 (£19,200) at auction, a solid price even for such a rare item.

Little Louis-Charles was not raised to become king. That distinction belonged to his older brother, Louis-Joseph. As the second son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, he was born the Duke of Normandy, and could expect a life of wealth, relative leisure, and perhaps prominence at court or as a patron of the arts and sciences. But Louis-Joseph died at age seven in 1789 after a brief illness, plunging his royal parents into deep mourning and making four-year-old Louis-Charles the future King of France and Navarre.

We have no way of knowing how the little prince felt when destiny placed him a heartbeat from the throne. At such a young age, he was unable to express himself, and in any event, tragedy had only begun to leave its fatal mark on his family. Just a month after Louis-Joseph's death in June 1789, the French Revolution began with the storming of the Bastille in Paris. In October, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Prince Louis-Charles, and his older sister Princess Marie Therese were moved from Versailles to the Tuileries Palace in Paris, where they were kept under house arrest.

For the next two years, they lived a secluded but peaceful life, undoubtedly clinging to the hope that the revolution would blow over, or that there would be a peaceful resolution that preserved the monarchy in some form. During this time, the Dauphin Louis-Charles underwent schooling appropriate for a future king. We know that he learned to write in a compact but fairly legible hand, for a catechism exists that is thought to be his work, with corrections added by his father. This writing matches that at the bottom of our unique copy-book page. And yet none of these much resembles the Dauphin's most famous signature, the story of which is profoundly sad and rather sordid.

In 1791, the royal family tried to escape its confinement, but failed and were returned to the Tuileries. Meanwhile, the flames of revolution, far from burning themselves out, became ever more intense as different radical factions vied for dominance and moderate elements were pushed aside. A deadly mob attacked the Tuileries in August 1792, and Louis-Charles and his family were moved to the Great Tower, a medieval fortress and prison in Paris. They were given the family name of Capet, for the Revolution no longer countenanced the monarchy, and soon Louis XVI was separated from his wife and children and put on trial for treason. He was duly convicted and executed on the guillotine January 21, 1793.

To royalists, the execution of Louis XVI made Louis-Charles the rightful King of France and Navarre as Louis XVII, a position reinforced when the Bourbons were briefly restored under his uncle, who was known as Louis XVIII. However, the boy would never take the throne. In July, he was taken from his mother and placed under the care of a cobbler and his wife. Accounts of his treatment differ greatly. It seems that he was neither starved nor neglected, but stories began to circulate that he was living a rough life full of the vices of the street. He was visited in October by agents of the revolutionary government, who induced him - reportedly by plying him with strong drink - to sign an affidavit accusing his mother, Marie Antoinette, of a wealth of heinous crimes, the most shocking of which was sexual abuse of the Dauphin himself. Louis' signature (as Louis Charles Capet) on the document is a shaky scrawl that differs from confirmed examples of his hand including our copy-book page, suggesting that he was, in fact, drunk when he signed it, and had ceased to be given regular lessons to keep up his penmanship.

This ugly incident was wholly unnecessary, for the worst accusations against the queen were disregarded at her trial. Nevertheless, the verdict of treason was never in doubt, and she shared her husband's fate in October 1793. The boy king was taken from the cobbler and placed in a cell, where he suffered neglect and became seriously ill. While he lived, he was a danger to the new French Republic. Princess Marie Therese, in contrast, was kept in seclusion but not denied ordinary human comforts, for under salic law, she could never succeed to the throne. On June 8, 1795, after a year of illness, King Louis XVII died in prison of scrofula (lymphatic tuberculosis), but his strange and sad history was not finished.

Because of the bizarre accusations against his mother, subscribed in such a strange hand; and because only his family's enemies saw him during the last several months of his life, the announcement of Louis-Charles' death was answered immediately with stories that he had escaped and was still alive, and that the boy who died in captivity was an impostor. Oddly, the revolutionary authorities did not simply have Marie Therese identify her little brother's body, and the tales came to have a life of their own. Throughout much of the 19th century, men would claim to be the "Lost Dauphin" of France, and therefore true heir to the French throne. Conspiracy theories were finally put to rest only in 2000, when DNA testing showed that the preserved heart of the little prisoner was indeed that of Louis-Charles, King Louis XVII of France.

|

|

Exceedingly Rare Louis XVII

Autograph of the "Lost Dauphin"

Price Realised:

$30,000/£19,200

|

Great moments in history, and the people who made them, are the stuff of autograph collectors' dreams. The French Revolution would dominate European history for a century, by giving birth to the Napoleonic era, by heralding the beginning of the end for absolute monarchies, and by providing a terrifying example of the form revolution could take, leading some nations to reform and others to reaction. To own an autograph from one of the personalities at the center of the revolutionary storm is to own a piece of our indelible history. The autographs of Louis XVI and of Napoleon have naturally been popular, and are necessary elements of any French Revolution collection, but their very prominence means that they are not at all rare. Less common is the writing of Marie Antoinette, or of revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre, though either can be found for the right price with a little work. Rarer still are revolutionary Georges Danton, who was himself executed during the Reign of Terror, and Joseph-Ignace Guillotine, who championed the humane device (compared to the scaffold) that came to bear his name, linking it forever with the Terror's thirst for blood. But the rarest and most desirable is the autograph of the Lost Dauphin, who lived half of his brief life under the shadow of revolution, and became a victim of the heedless march of history.