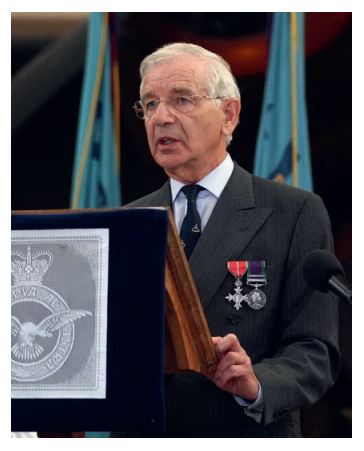

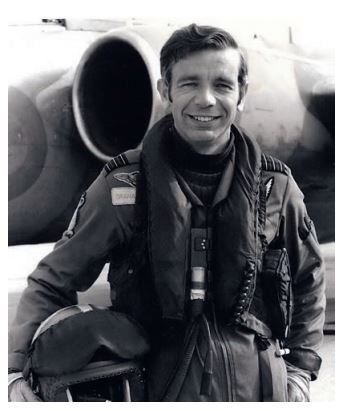

INSIDER 30 | AN INTERVIEW WITH AIR COMMODORE GRAHAM PITCHFORK, MBE, BA, FRAeS, RAF (Rtd) TO MARK THE CENTENARY OF THE ROYAL AIR FORCE

by David Erskine-Hill

Note: Air Commodore Graham Pitchfork is referred to throughout the interview as GP and David

Erskine-Hill as DEH.

DEH: Tell us about your distinguished career in the Royal Air Force; aside from the great responsibilities of senior command, I gather you were once seconded to the Fleet Air Arm?

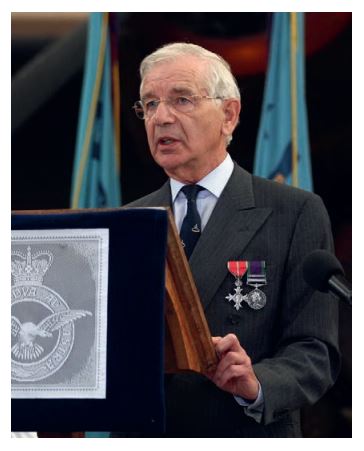

GP: It all began when I was a flight cadet at the RAF College in Cranwell where I gained a marvellous foundation for a full career in the RAF and trained as a navigator. After three years I joined a photographic reconnaissance squadron in Germany and this was followed by an exciting exchange posting with the Fleet Air Arm when I joined a new Buccaneer strike/attack squadron, and it was this aircraft that was to dominate my flying career over many years. During my time with the Navy I spent a year embarked in HMS Eagle, mostly in the Far East, and made 170 deck landings, including some exciting ones at night.

I later commanded a Buccaneer squadron, No 208, which had a rich heritage of service in the Middle East. I had a wonderful tour back at Cranwell as the Director of Air Warfare before commanding RAF Finningley, the largest flying training base in the UK. My last appointment, and my third in the MOD, was as a director of operational intelligence at a time when the Cold War had just come to an end and difficult times were breaking out in the Former Yugoslavia and in the Middle East.

DEH: This year we commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the Royal Air Force. How would you summarise the RAF’s role in that period, and do you foresee a different role for the force in the future?

GP: As a young officer I was reminded that, unlike the sea and the land, air covers 100% of the globe. From the earliest days of the ‘eye in the sky’ to the delivery today of incredibly precise weapons, the RAF has played a key role in every conflict. It has been crucial in providing support for land campaigns, battles at sea and gathering intelligence. It has transported people and supplies to every corner of the globe, provided rescue services and answered countless calls to deliver humanitarian aid. Underlying all these diverse capabilities are people – who have been, and still are, the crucial element.

These roles will still be important in the future but advances in technology will improve capabilities dramatically. Today, a single aircraft flown by one man can deliver more lethality than a squadron of Lancasters crewed by over 150 men.

We already operate unmanned aerial vehicles that carry weapons and reconnaissance sensors. Weapons are getting smarter and cyber warfare is becoming a factor in military capabilities and conflict. Then there is Space, which we already use for communication satellites – there will surely be greater use of Space. Despite all these new developments, the globe will still be covered by 100% of air so there will always be the need for an air force.

DEH: When did you start collecting medals and was there a notable catalyst? GP: I started as a serious collector over forty yearsago but my interest had been triggered when

I was a young teenager. One day I was sitting with my grandfather when he gave me two small, unopened white boxes and told me they were precious and he wanted me to keep them safe. When I opened them, they contained a British War Medal and a Victory Medal. They had never seen the light of day and were named to his son, a lance corporal in the York and Lancaster Regiment, who had been killed in October 1918 when he was 19 years old. A few weeks later my grandfather died.

I studied the details of my uncle’s final battle and have visited his grave near Cambrai, where I will be returning in October this year to be with him on the 100th anniversary of his death. His framed medals and photograph have always been with me and hang in my dressing room. In due course I started to collect medals to his regiment and then expanded it to concentrate on the RAF.

DEH: Your interest in the R.A.F. between the wars is well-known. Tell us little more about this aspect of your collection.

GP: The first squadron I joined was No 31 Squadron, whose badge is based on the Star of India with a motto of In Caelum Indicum Primus (First in the Indian Skies). It had been formed in 1915 and was, for a number of years, the only RAF squadron in the region. I was made responsible for maintaining squadron records – a very lucky appointment as it turned out because it gave me the chance to study the early days on the Northwest Frontier. I became fascinated in the whole period so, when I started my RAF collection, I looked for medals to squadrons involved in India and this led to a wider interest in the early days of the RAF overseas.

Years later my old squadron became involved in the Gulf War and so Iraq was a logical next step in my collecting interest. Today, with a son and son-in-law who have been heavily involved in operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, I have expanded my collection to cover the actions in Iraq between the wars, when Trenchard’s policy of ‘air control’ was the dominant military force in the area.

DEH: Tell us too a little about your interest in Second World War awards to the RAF.

GP: From my first day at Cranwell I served under officers with gallantry awards and rows of medals on their chests and I was eager to discover their exploits. Some were household names and their stories appeared in flying magazines and biographies. On my early squadrons, many of my colleagues had seen war service and I never tired of listening to their tales. So, when I first started my RAF collection I concentrated on World War Two and flying gallantry groups but always with a named medal in the group.

In researching the actions that led to these awards I have learnt a great deal about the conduct of the air war, and it has made me realise what a remarkable generation of young men and women they were and how their experiences need to be preserved. My admiration for what they did, and their sacrifices, is immense.

DEH: You are a much respected obituarist for The Daily Telegraph. Tell us a little more about that fascinating role. How to you go about it and how many obituaries have you written for the newspaper to date?

GP: I was very flattered and, I must confess, somewhat overawed when the newspaper invited me some fourteen years ago to become their aviation obituary writer. So far, the majority of those I have written about were veterans of the Second World War so my long-standing interest in the RAF’s activities during those times, and my interest in RAF medals, have both provedvery useful.

One of the first things I did was to establish a database of those most likely to justify an obituary and then gather information on them from a wide variety of sources. I also created another database of organisations and people that could provide information. I have a large library at home, many knowledgeable historian friends, and knowing my way around the National Archives has also proved very valuable. While the basic procedure for writing an obituary remains the same, each has its own unique aspects, and sometimes surprises! I always have to bear in mind that an obituary may be the only written record that survives for posterity. So, the key is to be accurate, fair and honest while always recognising the need for sensitivity and understanding. I will soon have written 600; the variety has been astonishing and I always find their exploits very humbling.

DEH: You are also known for a dozen or so published works, from ‘Your Men Behind the Medals’ titles to stories of evasion in the Second World War. Tell us a little more about your journey as an author and what have been your most recent projects?

GP: I more or less stumbled into becoming an author. After I retired from the RAF I decided to gather the papers I had on individual medal groups in my collection and write a covering biography. An RAF colleague had just retired and taken over as editor of a well-known aviation magazine and he asked if I could do an article on ‘RAF Medals’. I sent off one of these biographies and, to my astonishment, he published it. He wanted more, so Men Behind the Medals was born. There are now more than fifty and, over the years, they have been gathered into three books.

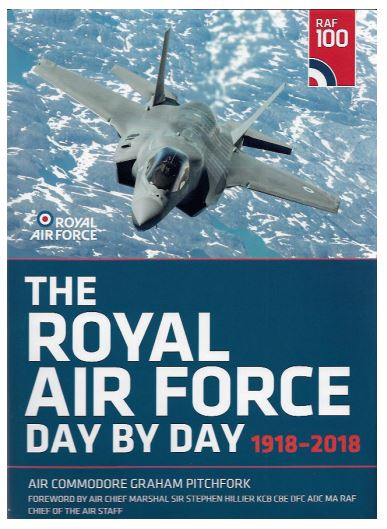

Other publishers have approached me, and the National Archives asked me to be a consulting editor and also invited me to write about RAF escapers and evaders. Shot Down and On the Run was the result which has just been reprinted for the third time. This was followed by a sister volume, Shot Down and in The Drink, a book about those who were rescued from the sea. I have done a couple of books on my favourite aircraft, the Buccaneer. Most recently, the RAF asked me to do a major book to commemorate its Centenary and a couple of months ago Royal Air Force Day by Day, a work that took me almost two years tocomplete, was published by the History Press.

DEH: You have been a busy and innovative President of the OMRS (The Orders and Medals Research Society) for several years. How do you see the Society’s future?

GP: I am now in my seventh year as President and it has been a stimulating, fascinating and challenging time, none more so than now. So much has changed since I started collecting forty-odd years ago. Gone are the days of catalogues through the post, bargains at local auctions or market stalls and limited research opportunities for those living away from the major institutions. In recent years I believe two of the main factors that have affected our hobby are the rising costs of medals and the Internet. The latter provides countless opportunities for research, we have seen auctioneers and retailers conducting much of their business through their websites and there are a growing number of forums and chat rooms, which have become the main medium for collectors to make and maintain contact with each other.

In some ways, the social side of the hobby appears to be on the decline, although our branch structure remains intact and is a crucial element of what the OMRS can provide, but there appears to be less inclination to attend events and fairs and to socialise and compare notes. As a society we have to take note of these developments and try to adapt, but the Society relies entirely on a small and dedicated group of unpaid volunteers to implement changes. An area of particular concern is the difficulty in attracting the younger generation. It has become a very expensive hobby for a beginner and they have very different ideas on communication. In an effort to engage more of our widespread membership, we decided to make our flagship event more accessible to them and this involved moving our annual convention away from London, which has been a success. The weekend programme encourages members to exhibit and those willing to do so have increased; the standard is spectacular. The dealers remain a key element of the weekend and it has been very encouraging to see their support for the changes we have made.

Another area I have tried to foster is our liaison with overseas societies. We already have a number of well-run and enthusiastic OMRS branches in the Commonwealth and we have always enjoyed a close relationship with our colleagues in the USA and with OMSA (The Orders and Medals Society of America). In recent years, we have made a determined effort to join our European friends at the annual phaleristic conferences held in various European cities, including the very successful one hosted by the OMRS in London in 2015. These are very enjoyable and informative: our collective thoughts on the way forward are important and valuable, and we can all learn from each other. I do see closer liaison on the international stage as a way of attracting more members. There is no doubt that the years ahead are going to be challenging, but we are determined to be a major part of any new developments.