INSIDER 30 | THE MAN BEHIND THE MEDAL: SUB LIEUTENANT CLAUDE D. BURY, RN

by Iain Goodman

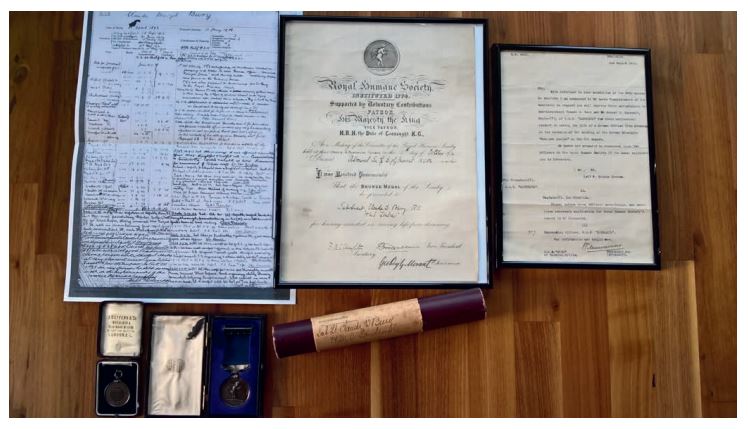

As someone who has been passionate about medals for over a decade, I have always been drawn to a good story and the opening hours of Bury’s Great War are undoubtedly something to tell the grandchildren; not only did he receive one of the first, if not the first award of the Great War, but, in a war which went on to take the lives of millions through conflict and disease, his medal was not for taking life but for attempting to save life.

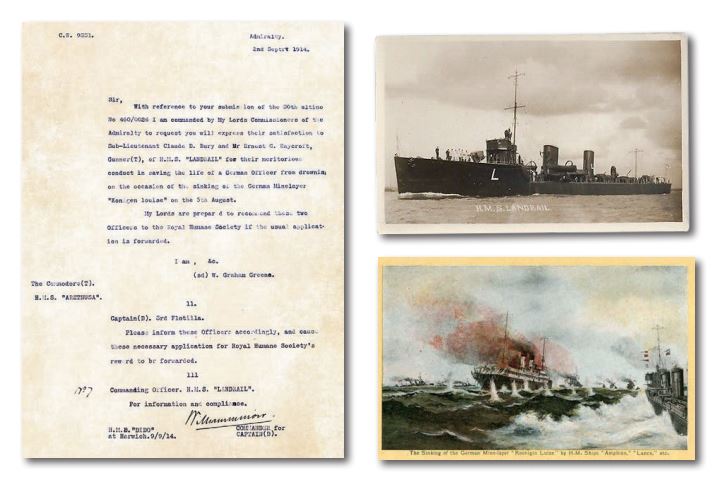

Rather than attempting to save a friend or fellow serviceman, Bury jumped into the North Sea in order to hold aloft an injured German Naval Captain, a man who minutes earlier had done his best to entice Bury’s destroyer upon a newly laid path of mines. Claude Denzil Bury was born on 27th April 1893 in Kensington, London, the son of Henry E Bury and his wife Angela. His father was a solicitor and in 1901 the family were residing at Mottistone Manor House on the Isle of Wight. Today the property is owned by the National Trust, but it has a long history as ancestral home to the Seely family and was mentioned in the Domesday Book. Aged just 11 years, Claude left home and entered the Royal Navy as a Naval Cadet on 15th January 1906. Appointed Midshipman on 15th May 1911, he was commissioned Acting Sub Lieutenant on 15th September 1913 and was posted from the naval depot Dido to HMS Landrail in June 1914; built by Yarrow and launched on 7th February 1914. The Landrail was one of 22 Laforey Class torpedo boat destroyers, powered by steam turbines and capable of 29 knots, armed with two pairs of 21 inch torpedo tubes and three 4-inch 102mm Mk IV guns.

The Great War started officially for Britain at 23.00 hours on 4th August 1914. Across the North Sea, the Kaiserliche Marine had busily spent the previous 24 hours converting the former excursion steamer Konigin Luise into an auxiliary minelayer, capable of deploying 200 mines. In such haste, priority was given to a repainting job; with two raked funnels and two raked masts, she resembled the Great Eastern Railway steamers that plied their trade between Harwich and the Hook of Holland. The German ship was therefore disguised in the Great Eastern Railway steamer colours –black hull, buff superstructure and yellow funnels with black tops. There was no time for the main armament of two 3.4 inch guns to be mounted, indeed when she sailed from her base in Emden that evening, she carried no more than a pom-pom and small arms; her deck still had the enclosed glass windows.

Meanwhile, at the Port of Harwich, HMS Amphion under Captain Cecil H Fox, and the Destroyers of the Third Flotilla, including HMS Landrail, prepared to sail and conduct a sweep towards the Heligoland Bight. The weather ahead seemed indifferent with heavy showers and choppy seas. En route they encountered a fishing vessel, whose crew informed the British ships that they had seen a vessel “throwing things over the side,” about 20 miles north of the Outer Gabbard. Fox had inadvertently stumbled across the Konigin Luise attempting to mine the entrance to the Thames Estuary. The hunt was on.

At 10.25 the Amphion sighted the German ship and sent the destroyers Lance and Landrail to investigate. The enemy immediately fled south-east at 20 knots, but unable to outpace the destroyers, attempted to seek shelter in a rain squall. The reduced visibility gave opportunity to deliver a few more mines and hopefully lure her pursuers into a trap. It failed. At 10.30 Lance signalled she was to engage the enemy and fired the first shot of the war from her quick firing 4 inch gun. The other destroyers then joined in and the Konigin Luise was riddled with shell bursts and small arms fire. Commander Biermann had little choice but to order the abandoning of his ship and scuttling of the vessel; 46 surviving crew from a compliment of 100 men jumped into the water, many struggling to hold their heads aloft in the choppy waters flung up by the squall and wakes from the destroyers. Witnessing the struggles of the German sailors in the water, it was then that Bury and a gunner, Ernest G Haycroft, jumped into the water and held the grievously injured Biermann aloft. In the meantime, the Konigin Luise rolled over to port and sank at 12.22, the suction no doubt dragging many an injured man to the depths. The three men were hauled about Landrail and mobilisation papers were found upon the German Captain. He would succumb to his injuries a few days later. As a result of their efforts, on 2nd September 1914, Bury and Haycroft were recommended to the Royal Humane Society:

‘I am Commanded by my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to request you will express their satisfaction to Sub Lieutenant Claude D. Bury and Mr Ernest G. Haycroft, Gunner (T) of H.M.S. Landrail, for their meritorious conduct in saving the life of a German Officer from drowning on the occasion of the sinking of the German Minelayer Konigin Louise on 5th August. My Lords are prepared to recommend these two Officers to the Royal Humane Society, signed W. Graham Greene, Captain (D), 3rd Flotilla.’

That same afternoon, the destroyers continued their sweep of the North Sea and very soon spotted another ship which resembled the Konigin Luise, this time trailing a huge German flag. It was the St Petersburg returning Prince Karl Lichnowski, German Ambassador to Britain, back to Germany. As so often happens in the confusion of war, the breakdown of communications almost created a significant incident; it was only the quick thinking of Captain Fox, placing the Amphion between his destroyers and the St Petersburg and hence fouling the range, that forced his ships to call off the attack, thus preventing a major diplomatic incident.

After 24 hours on patrol, the British force headed home back to Harwich; at 06.30 on 6th August, the Amphion hit a mine, possibly laid by the Konigin Luise the previous day. With her back broken and her forepart on fire, the Amphion began to settle by the bows. The destroyers came in to rescue survivors including those Germans plucked from the sea previously, but at 07.03, she struck a second mine; 148 sailors died from Amphion’s crew of just over 320. Eighteen German prisoners from the Konigin Luise also died.

From the records of Sub Lieutenant Bury, one can summise that the opening couple of days of the war had a significant impact upon his career path, and led to a deep fondness for HMS Landrail and torpedo craft in general. Noted repeatedly as ‘an exceptionally capable officer,’ by his superiors, his powers of leadership appeared to flourish during the war and he was highly commended for his extremely gallant manner following a collision in the North Sea. He repeatedly requested to remain with Landrail and was present aboard her at Jutland. He was also mentioned on three occasions, including the despatch of Vice Admiral Keyes for distinguished services during the raid on Zebrugge-Ostend from 22nd-23rd April 1918. In the post war years, Bury served in the Middle East and was noted for ‘his skill in navigating the Persian and Arab coasts,’ but despite a string of glowing recommendations in the early 1920s, his promotions stalled at the rank of Commander, much to the consternation of a few senior officers.

By the 1930s and in the twilight of his career, Bury’s service record notes comments such as ‘personality not outstanding,’ and ‘I am not enthusiastic about his social qualities. Is slightly unbalanced in this respect.’ It is hard to understand what happened to Bury over these years as the evidence is brief and glosses over any real facts, but what is clear is that he fell out of love with the Royal Navy. A search of the newspaper archives gives a potential snippet and line of enquiry on 8th December 1951, but I am down to mere speculation: ‘For One Week on bail – Claude Denzil Bury (58) of The Cottage, Corn Hill, Bishop’s Waltham, charged with being under the influence of drink to such extent as to be incapable of having proper control of a vehicle.’

Claude Denzil Bury, RN, died in Winchesteron 17th March 1957 aged 64. What tales he could tell.