INSIDER 29 | SPECIAL FEATURES | The Story of Hazel, Lady Lavery: The woman behind the banknote classic

By Jonathan Callaway

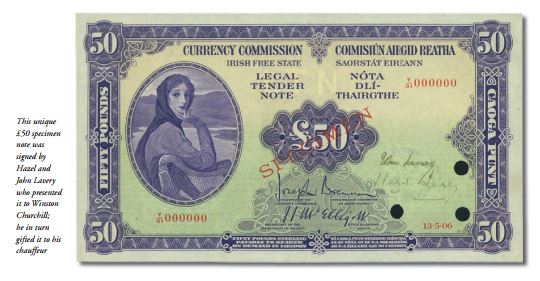

Ireland’s Legal Tender notes, first issued in 1928, count amongst the most iconic and beautiful of all modern banknotes. The story of how Hazel, Lady Lavery, an American woman born as Hazel Martyn, came to appear on Ireland’s banknotes for nearly fifty years (over seventy if one includes the watermark on later issues) is fascinating and intriguing. This article looks at her life and the genesis of the classic banknote design.

Hazel’s Early Years

Hazel Martyn was born in Chicago on 14th March 1880. She was a sixth-generation Irish-American descended from a branch of the Martin family of Galway, one of whose members had emigrated to America in the 17th century. The Martins count as one of the so-called fourteen tribes of Galway, wealthy merchant families mostly of Norman origin who dominated Galway life from the 13th to the 16th centuries and beyond.

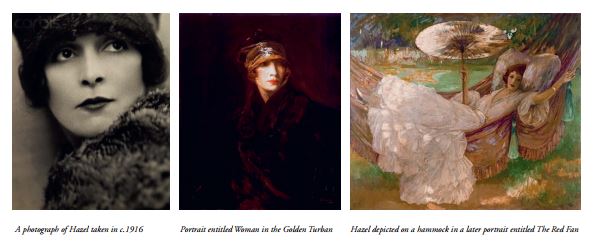

Her father was a successful businessman but sadly, when Hazel was just 17, he died and the family’s fortunes suffered as a result. She was nevertheless sent to finishing school and became well known in Chicago high society circles as an astonishingly beautiful young woman with many male suitors, attracted not only by her beauty but also her exuberant and, some have said, somewhat flirtatious character. She travelled regularly to Europe to pursue her artistic studies and was developing as a talented painter when she first met John Lavery in 1903 at an artists’ retreat in Brittany. He was an already famous Belfast-born, Scottish-raised and London-based society portraitist and landscape painter and 24 years older than her. Her mother disapproved of what appeared to be a blossoming relationship and shipped her back to New York to marry her fiancé Ned Trudeau later the same year. Tragically he died months later when she was already expecting her daughter Alice. The birth was difficult and she needed many months to recover, during which time she began writing again to John Lavery.

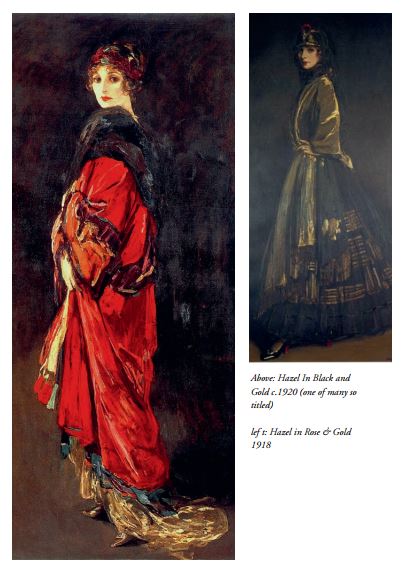

Hazel travelled to England with her mother in June 1905 to stay at a spa in the Malvern Hills. Lavery became a regular visitor and painted what is believed to be his earliest portrait of her, La Dame en Noir (The Lady in Black). Another 400 portraits followed over her lifetime. He was clearly totally smitten! Her mother’s constant presence deterred the renewal of the relationship – she remained adamantly opposed to Hazel marrying the much older man – and it was only her death in June 1909 that allowed them finally to marry. Prior to that Hazel had briefly been engaged to another man, Leonard Thomas, a wealthy American diplomat she had met in Rome in 1906, but that did not last.

Who was the man she finally married, having fallen for him several years earlier? Born in the Irish province of Ulster in 1856 to a Catholic family, raised in Scotland where he first began his artistic career, he achieved celebrity status in England as a portraitist to royalty and high society. John Lavery was a very determined and single-minded, ambitious and extremely hardworking man (to some, a driven workaholic who had neglected his family). He became one of the Glasgow School of artists and first came to national prominence in 1888 when he painted the scene of Queen Victoria’s State Visit to Glasgow. He individually detailed the faces of all 253 attendees at the formal audience (working from photographs), then made sure he was subsequently introduced to each one of them to gain further commissions.

He moved to London soon after and continued to build his reputation as the society portraitist of choice. He was thus very well established when he first met and so impressed Hazel. After they married in 1909 they moved into his spacious and luxurious home at 5 Cromwell Place, near the Victoria & Albert Museum, where Hazel took on the role of a London society hostess, presiding over endless dinners and soirees, all the while charming the men who came to visit and guiding them carefully into her husband’s studio for yet another society portrait.

The extent to which her flirtations, always known to and tolerated by her husband, became full-blown affairs is somewhat uncertain but she did strike up firm and very close friendships with a number of notable men, not least Winston Churchill who credited her with teaching him to paint while he himself was sitting for John. She certainly subordinated her own artistic ambitions to her husband’s – and became his muse instead. But it is clear she enjoyed being the centre of attention and her role as a London society hostess enabled her to exploit that to the full. Jealous rivals hinted at vanity and suggested she exaggerated the degree of affection some male admirers developed for her. In 1913 John painted King George V and his family, the portrait becoming a great popular success. When war broke out in 1914 he was appointed as an official war artist and produced many memorable canvases. He was knighted in 1918 and elected to the Royal Academy.

Hazel’s Role in the Irish Independence Negotiations

During the wartime years tensions mounted between Ireland and Britain, culminating in the 1916 Easter Uprising and the Anglo-Irish War of 1919 to 1921 following the Sinn Féin election victory of 1918. Both Hazel and John had long been conscious of their Irish roots but now became passionate about the Irish cause, in Hazel’s case a powerful motivation being her witnessing of the trial of Roger Casement, a court scene painted by John. Casement was convicted of high treason for seeking to arm Irish rebels with German weapons and was executed in August 1916.

The Laverys wanted to use their social and political contacts on both sides of the Irish Sea to try and reconcile Britain and Ireland. They prevailed on Sir Shane Leslie, an Anglo-Irish landowner (and first cousin of Winston Churchill) who had turned Catholic and become an Irish nationalist, to facilitate contacts on the Irish side. As a result they came to know John Redmond, Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and other leading Irish figures of the independence campaign.

Following the truce in July 1921 the Irish Government despatched a delegation to London for negotiations with the UK Government. The delegation was led by Collins and they became regular visitors to 5 Cromwell Place, felt to be suitably neutral territory and a place where they could meet their interlocutors informally. Some members of the delegation were however suspicious that Hazel, who had begun to develop a close relationship with Collins, might have been a spy. But she won them over with her sincerity and the fact that she courted unpopularity in London society circles due to her increasingly evident Irish nationalist sympathies. She started to describe herself as “A simple Irish girl” and converted to Catholicism.

Collins and Churchill met and got to know each other at the Laverys, who also had close social links to other British political figures such as Lloyd George, Austen Chamberlain and Lord Birkenhead. They also knew Lord Londonderry, a leading figure in the Protestant opposition in Northern Ireland. These social links were carefully drawn together by Hazel who used them to enable bitter political opponents to meet away from the conference room. Many contemporaries recognised the valuable role she played and her voluminous correspondence shows she worked hard to influence events and opinions. She was a strong advocate of a united Ireland and campaigned against Partition, to no avail in the end. It was also rumoured – in fact assumed – that she and Collins began a love affair but he had got engaged only days before he came to London and his fiancée Kitty Kiernan later met and became friendly with Hazel. This plus the fact that they embraced in public at his funeral makes assumptions of an affair rather difficult to sustain. Hazel’s close relationship also with Churchill had led to intense speculation that she had entered into an affair with him too. Maybe; the true facts remain unproven and of course she had close relationships with many other men, most of whom ended up sitting for her husband and were part of her wider social circle. When Collins was assassinated in 1922 he was carrying a letter he had written to her, addressing her as “Dearest Hazel”, sufficient evidence for many that they were indeed having an affair. Elsewhere the phrase “romantic infidelities” was used, allowing enough room for some to believe her liaisons did not extend beyond the platonic. Anita Leslie, wife of Sir Shane Leslie, put it pithily (of Collins and Hazel): “they were soul mates rather than bed mates”. Another prominent Irish politician who became close to Hazel was Kevin O’Higgins. He became an ardent admirer of hers – if not her lover – and was one of those who floated the idea of making Sir John Lavery the first Governor General of Ireland. Hazel would have loved it but realised it was absolutely out of the question: “Dubliners would have objected violently”, she said, if “a Belfast knight and his Irish-American lady” had taken on this role. The idea never went anywhere and when O’Higgins was assassinated in July 1927, Hazel was left just as distraught as she had been on Collins’s death.

How Hazel’s Image Appeared on Ireland’s New Currency

The events leading to the selection of a portrait of Hazel to adorn the Irish Free State’s new currency illustrate just how close relationships had become between the Laverys and leading members of the new Irish Government.

Soon after Independence in 1922 the decision had been taken to create a new currency for the Irish Free State. Until then the British Pound Sterling had been the currency of Ireland and circulation dominated by the banknotes of the six commercial bank issuers of the day, alongside Bank of England and, after 1914, British Treasury notes. It was however recognised that a distinctive currency and a separate issuing authority needed to be established in the newly independent state.

In March 1926 the Irish Government set up a Commission of Inquiry and its main recommendations were incorporated in the currency Act of September 1927. This provided for the establishment of a Currency Commission to oversee the introduction of a new Irish currency, the “Saorstàt Pound” and prepare for the issue of both coins and Legal Tender Notes. These were intended to replace the notes of the six commercial banks, while an interim series of “Consolidated Bank Notes” (the famous Ploughman notes) would enable the commercial banks to continue to enjoy some of the benefits of their note issues although now strictly under the auspices of the Currency Commission.

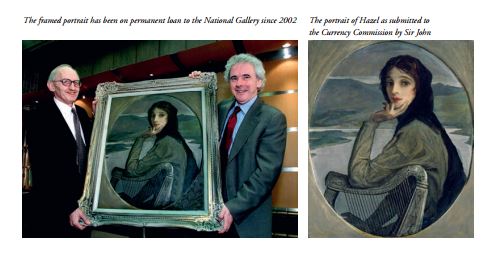

An advisory committee was set up by Joseph Brennan, the Chairman of the Currency Commission, to look at designs for the new notes. Among the individuals appointed were Dermod O’Brien, President of the Royal Hibernian Academy, and two Directors of the National Gallery, Thomas Bodkin and Lucius O’Callaghan. A selection process of sorts took place prior to the commissioning of Sir John Lavery to paint an “emblematic female figure” to feature on the new Legal Tender Notes. It is known that printers other than the eventual winners Waterlow & Sons were approached to submit design proposals.

The decision to commission Lavery was taken in December 1927 and he was appointed in January 1928. Bodkin, who had become a close friend of the Laverys, again thanks to Hazel’s efforts, clearly influenced the decision to appoint Lavery. It is also clear that Brennan essentially micro-managed the finalisation of the designs with much of the design detail, choice of watermarks and many other features receiving his close attention. He was however guided on artistic matters by his committee members.

Why was Lavery chosen and how did yet another portrait of his wife, an American woman closely associated with the British aristocracy, become the symbol of Ireland on the new notes? The Commission had already decided they wanted an archetypical Irish Cailín or Colleen, symbolic of Irish womanhood, on the notes, the mythical Cathleen Nihoolihan figure as depicted in the one-act play by W B Yeats.

Was Lavery chosen just because he was available and they needed to move quickly? Was it also in recognition of his close involvement in and support for Irish affairs during the independence negotiations? Shortly prior to Lavery’s appointment Hazel had been trying to get Bodkin appointed as Irish High Commissioner in London, so perhaps there was an element of reciprocity in the decision? Bodkin was hoping amongst other things to persuade the National Gallery to accept some thirty portraits offered as a gift by Lavery. It was certainly Bodkin who first suggested putting an image of her on the notes. Lavery, rightly or wrongly, assumed that this was 52 WINTER 2017 the Commission’s intention all along and was of course more than content to go along with this.

When Hazel realised her face would be the one on the notes she wrote to Bodkin: “I really feel that you are too kind and generous when you suggest that my humble head should figure on the note, and you know I said from the first that I thought it wildly improbable, unlikely, impractical, unpopular, impossible that any committee would fall in with such a suggestion. Indeed apart from anything else I think a classic head, some Queen of Ireland, Maeve perhaps, would be best, someone robust and noble and fitted for coinage reproduction ...”

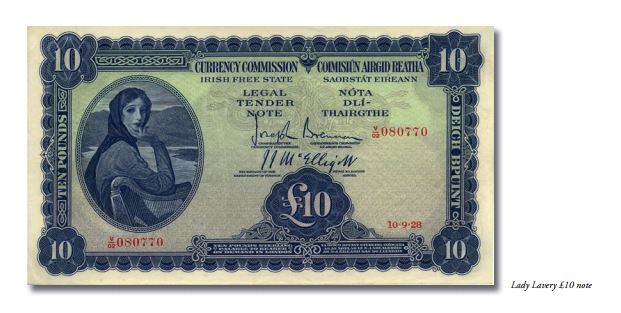

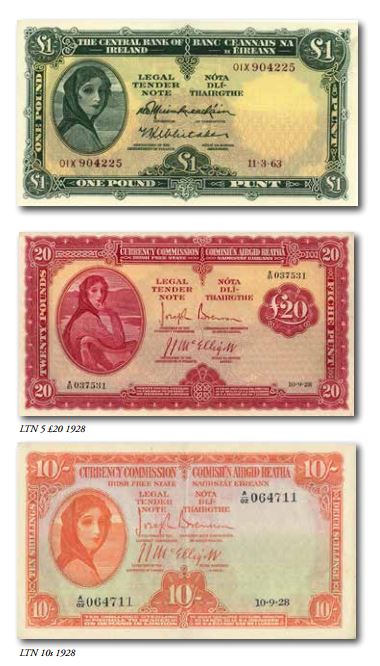

Lavery produced the painting within a fortnight and charged a fee of 250 guineas. Unusually, but as had been requested, this was completed on an oval canvas which is now in the possession of the Central Bank of Ireland and on permanent loan to the National Museum in Dublin. A demure Hazel is depicted facing left, in a fi ne Irish shawl, her arm resting on an Irish harp with a classic Irish landscape of lakes and mountains in the background. Once the portrait had been painted and submitted it was quickly accepted by the Commission, but when the notes came out in September 1928 they were accompanied by official denials that it was her.

Kenneth McConkey in his book “Sir John Lavery” states that the portrait is not typical of Lavery’s work; “... it lacks the active paint surface which characterises the immediacy of his style. Its colours are dull and muted and in general terms, the work has something of a mural-like quality ... These stylistic devices obviously made it easier for the work to be photographed and then engraved”.

Rumours abounded that the portrait on the notes was Hazel, hardly surprising as the likeness was rather obvious. The official denials were issued due to worries about a possible backlash given her relationships with both Collins and O’Higgins, but the notes were soon accepted and her portrait taken to be an apolitical portrayal of Ireland, as the Commission had intended from the outset. Sir John Lavery was subsequently awarded the Freedom of Dublin and became the fi rst man to have received that honour from both Dublin and Belfast (where he had also donated numerous portraits to the City Council).

Unlike the original portrait, Hazel is depicted facing right on the notes because it had been decided to place the portrait on the left of the note. The full portrait appears on the four higher denominations of £10 and above but is reduced to a head and shoulders version on the 10/-, £1 and £5 notes.

The reverse of each note featured one of the river masks whose sculptures adorn the facade of the Dublin Custom House. There were fourteen such masks, all sculpted by Edward Smyth in 1790, representing Ireland’s thirteen principal rivers and the Atlantic Ocean. Again, the Commission spent time deciding which ones to use and amongst those discarded was the one representing the Liffey, Dublin’s own river.

Belfast’s river, the Lagan, did however make it on to the back of the £5 note. Were artistic or political considerations at play here?

The watermark on the notes, the Head of Erin, was based on a work in the National Museum by the Irish sculptor John Hogan. Hazel had heard that the sculptor had used his Italian wife Cornelia Bevignani as the model and she wrote rather unkindly to Bodkin: “Do find out if the fat female symbolical figure of ‘Erin’ as the watermark is a portrait of the late Mrs Hogan and whether she was born and bred in Ireland …”. She knew the answer full well, of course!

One suspects her earlier attempts at modesty at being featured on the new notes were not exactly genuine and she was able to enjoy the irony of sharing the note with another non-Irish female figure.

After 1929 Hazel and John remained based in London but continued to travel frequently to Ireland. Her involvement with Irish affairs continued but as a result of political changes she became less close to those in power in Dublin. Her health, never that good, deteriorated following an operation to remove a wisdom tooth, and she died in January 1935. John survived her, moved permanently to Ireland in 1940 and died in Kilkenny in January 1941. He was buried next to her in London’s Putney Vale cemetery, where they share a very simple unadorned gravestone. Outside their former home in Cromwell Place a blue plaque commemorates John but makes no mention of his wife.

Hazel’s valuable role in the Irish independence negotiations is largely forgotten today and Sir Shane Leslie’s view (quoted by Sinéad McCoole) provides a concise epitaph: “Had it not been for Hazel’s portrait as the colleen of Irish banknotes, her features and even her name would now be forgotten in a land which has never accounted gratitude amongst its theological virtues”.

Acknowledgements

Blake, Bob & Callaway, Jonathan: Paper Money of Ireland, London 2009 Brennan, Caroline & Britton, Helen, an educational film 2016: Hazel: A Simple Irish Girl?

(A GiantLeap Production available on http://www.giantleapproductions. ie/hazel-a-simple-irish-girl)

Moynihan, Maurice: Currency and Central Banking in Ireland 1922-60, Dublin 1975 McConkey, Kenneth, Sir John Lavery, Edinburgh 1993

McCoole, Sinéad: Hazel, A Life of Lady Lavery 1880-1935, Dublin 1996

MacDevitt, Martan: Irish Banknotes – Irish Government Paper Money from 1928, Dublin 1999