INSIDER 29 | COLLECTOR'S CORNER | Selling Collections to Help Solve Global Challenges

By Jakob von Uexkull

When he was nine years old, Jakob von Uexkull’s father offered to exchange his son’s toy pistols for a stamp collection. Jakob agreed and never regretted his decision. A few years later, after moving from Sweden to Germany, he noticed that Swedish and German stamps were considerably more expensive in their respective home countries and began dealing in his free time. His business grew and when he won a scholarship to Oxford, his college complained that he was receiving more mail than the Dean…

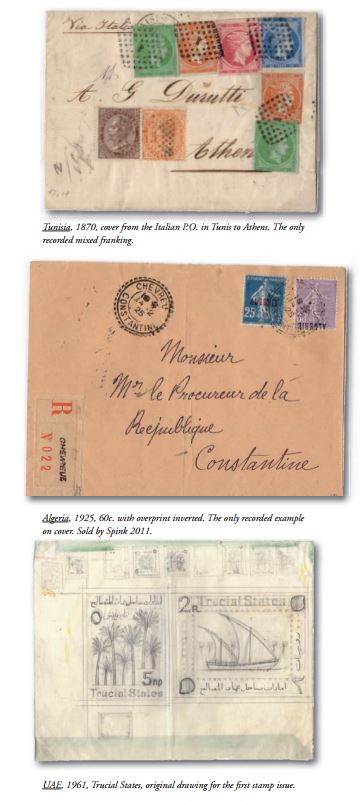

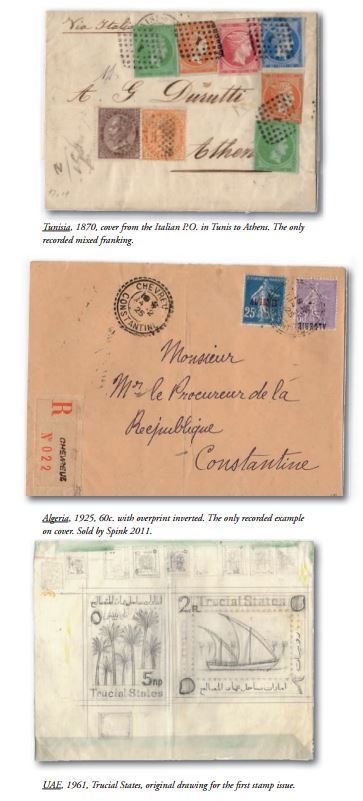

After graduating he travelled the world, combining journalism – following in his father’s footsteps – with philately. He also worked as a freelance describer for several major auction houses, to deepen his knowledge of postal history and rare stamps. He loved hunting rare covers from exotic countries, but eventually decided to specialise in the Arab world.

He was particularly fascinated by the postal history of Saudi Arabia, of which very little was known. Seeking out and visiting specialists, he secretly assembled a unique collection of rare covers which was first displayed at the WIPA Exhibition in Vienna in 1981 where it was awarded the first International Large Gold Medal ever for a collection of Saudi Arabia. It was later shown at the Collectors Club, New York, and featured in publications like ARAMCO World Magazine. But, to von Uexkull, rare stamps and postal history, while fascinating, were always a means to an end. “I could never understand,” he says, “why we live with problems we can solve.”

During his travels, he not only discovered philatelic rarities, but also pioneering individuals working on solutions to many global challenges, and he decided to make them better known. Having grown up in Sweden, Jakob knew that Nobel Prizes confer instant fame and recognition. He therefore proposed to the Nobel Foundation the introduction of an additional Nobel Prize for the Environment as, he says, “a healthy natural environment is the pre-condition for everything else.”

To ensure that his proposal was taken seriously, he offered to fund the new award at the beginning and was prepared to sell his collection and stock of other rare stamps to do this. When the Nobel Foundation turned him down, he decided to go ahead on his own, with a new prize he called The Right Livelihood Award, highlighting the need to “live lightly on the Earth and not use more than our fair share of its resources.” As they were presented in Stockholm just before the Nobel Prize ceremony, his awards soon became known as ‘The Alternative Nobel Prize’.

Right Livelihood prize money is less than the Nobels, as, von Uexkull jokes, “dealing in postage stamps is less profitable than inventing dynamite!” But they have become globally well-known and respected, with inspiring and courageous recipients, and for many years have been presented in the Swedish Parliament.

While managing the awards and hunting for worthy recipients, von Uexkull continued his philatelic career, both as a professional and collector. He also managed a short foray into politics, serving one term as a Member of the European Parliament “to understand how our political system works.”

He expanded to collecting the postal history – and old bank notes – of all the countries of the Arab league, showing extracts from his collections in Abu Dhabi (Invitee Class 2011) and at the Doha UPU Congress in 2012, where he won one of only two International Gold Medals awarded at that exclusive exhibition. Many of his country collections have been displayed at the Royal Philatelic Society in London, and his Postal History of Muscat and Oman was recently featured at the Museum for Communication in Berlin.

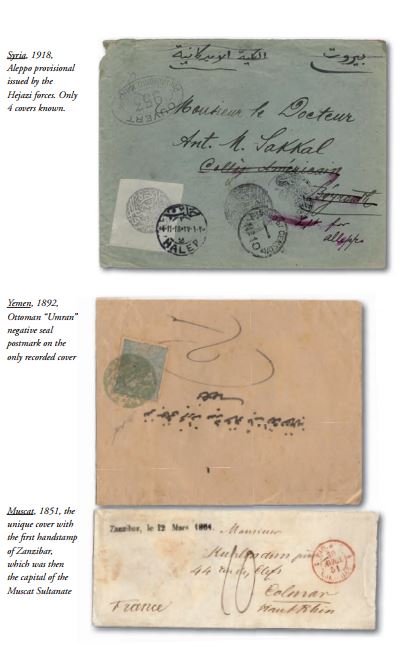

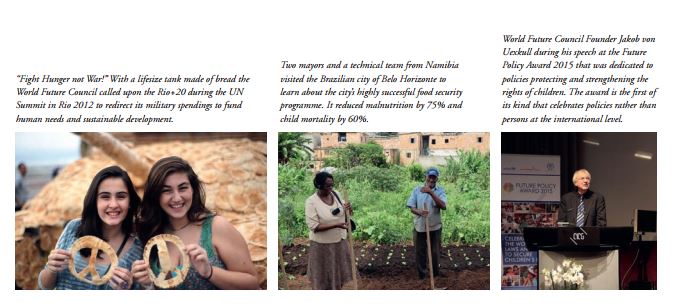

Needless to say, von Uexkull has been a long-standing client of Spink, where he has acquired many rare items. His recent decision to part with some of his collections and sell them through Spink is another fascinating story, after he realised there was still a piece of the puzzle missing if we want to give our children and grandchildren the same opportunities we have, especially a healthy planet. His conclusion is that this requires not just the promotion of best practises, but also spreading “best policies” – the best available policy solutions to important problems. “I realised we need a ‘race to the top’ of best policies,” he says. “When you start looking, you almost always find a policy solution in some city, region or country which is very effective in tackling a specific issue. Thus, the Brazilian city of Belo Horizonte has a remarkable food security policy which has reduced hunger by 75%; Rwanda has the most effective re-forestation policy; the Pacific island nation of Palau the best policies to protect ocean and costs; Costa Rica the best biodiversity laws; Germany the most effective policy to speed up renewable energy production; and the US State of Maryland the best environmental education policy.

To publicise and spread such exemplary policies, von Uexkull brought together 50 global pioneers in the World Future Council (WFC). The WFC enables MPs, Mayors and other dignitaries to learn from each other how such policies work and can be adapted to their needs. It bridges the gap between academic research and the day-to-day needs of busy policy-makers for information and capacity-building, using WFC’s “unique convening powers” (to quote a Canadian MP).

The WFC – with its broad global membership – also works to ensure that future generations are not forgotten when decisions affecting them are taken. Thus, it has promoted the concept of ‘Guardians of Future Generations’, like the Sustainable Futures Commissioner recently established in Wales, and is now working to create a UN High Commissioner for Future Generations. While this work is clearly vital to safeguard our shared future, von Uexkull is still looking for partners to help take it forward. In the meantime, he is selling his collections to keep the WFC going, quoting Winston Churchill: “In a crisis it is not enough to do your best. You have to do what is necessary.”